Credibility of USD Dominance in an Era of Uncertainty

DOI:

https://doi.org/10.35945/gb.2025.20.010საკვანძო სიტყვები:

USD, renminbi, gold standard, currency weaponization, rise of Chinaანოტაცია

The United States dollar (USD) has long served as the cornerstone of the global reserve currency system, maintaining its dominance for several decades. Nevertheless, this preeminence is increasingly challenged by a landscape characterized by geopolitical strife, shifts in economic power, and advancements in monetary technology. This paper investigates the validity of USD supremacy in light of China’s ascendance as a formidable economic force and the rising discussions surrounding a potential reversion to the gold standard. The analysis focuses on China’s expanding role through initiatives such as the internationalization of the renminbi (RMB), which aims to transform global trade and financial frameworks. Additionally, the paper considers both the historical and modern ramifications of a gold-backed monetary system, assessing its viability as a substitute for the current reliance on fiat currencies. Employing a multidisciplinary perspective, the study examines the interactions among these elements, offering insights into the durability of USD dominance and the potential for a multipolar currency landscape.

Keywords: USD, renminbi, gold standard, currency weaponization, rise of China.

Introduction

The United States dollar (USD) has functioned as the bedrock of the international financial and economic system since the mid-20th century, acting as the principal reserve currency and enabling global trade and investment. This preeminence has been bolstered by the substantial size and stability of the U.S. economy, the robustness of its financial markets, and the political and military clout of the United States. Nevertheless, the present climate of uncertainty, characterized by evolving geopolitical alliances, economic upheavals, and rapid technological progress, poses considerable challenges to the ongoing dominance of the USD.

A significant element contributing to this uncertainty is the emergence of China as a formidable global economic force. Through initiatives such as the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) and the advocacy for the renminbi (RMB) in international commerce, China aims to contest the dollar’s pivotal role in global financial architecture. Concurrently, there has been a resurgence of interest in the possibility of reinstating a gold-backed monetary system, driven by apprehensions regarding inflation, soaring sovereign debt, and the perceived volatility of fiat currencies. These trends prompt critical inquiries into the reliability and prospects of USD supremacy in the shifting global context.

This paper intends to investigate the fundamental components underpinning USD hegemony and assess the factors that jeopardize its sustained dominance. It will analyze the historical development of the dollar’s position, the tactics employed by emerging economic powers to curtail its influence, and the ramifications of alternative monetary systems, such as the gold standard. By integrating economic, political, and historical analyses, the research aims to offer a thorough understanding of the challenges facing USD credibility and the potential trajectories for the future of global currency relations.

Risk and threats

There are three primary reasons why the US dollar continues to be the reserve currency of choice globally. One is that the US is a traditionally strong sovereign nation, backed by robust, persistent economic growth. Another is the democratic nature of the US government and its institutions. The international community trusts in the stability of its overarching structures. Third is a degree of inertia—the difficulty in changing the structure of global finance revolving around the dollar and US capital markets. Competing nations can boast some of these facets, but the US maintains all three advantages.[1]

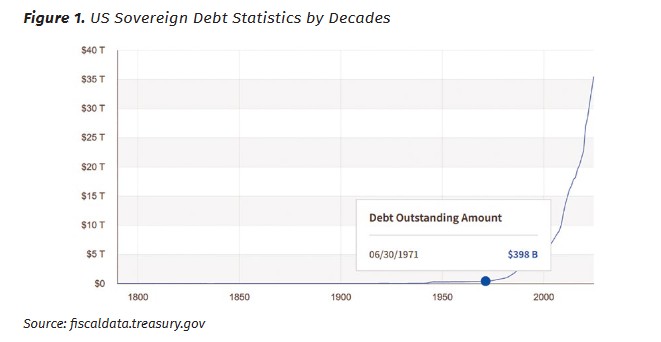

Let’s take a look at all the above-given criteria and see how their conditions look right now. The examination of the sovereign debt situation reveals a complex historical trajectory. The U.S. sovereign debt crisis has developed over several centuries, influenced by a variety of historical events, economic fluctuations, and decisions regarding fiscal policy. Initially, in 1790, the nation faced a debt of $75 million, which grew substantially during periods of conflict, notably during the Civil War and World War II, when the debt exceeded 100% of GDP in 1945. The acceleration of debt in contemporary times began in the 1980s, driven by tax reductions, heightened military expenditures, and increasing entitlement commitments, resulting in a tripling of the debt to $2.6 trillion by 1988. The financial crisis of 2008 represented another pivotal moment, as emergency fiscal measures escalated the debt from $10 trillion in 2008 to $15 trillion by 2011. The situation worsened during the COVID-19 pandemic, with the debt soaring to $33 trillion by 2023, alongside a debt-to-GDP ratio of 123%. In 2023, interest payments alone reached $475 billion, with projections indicating they could exceed $1 trillion annually by 2033. The current fiscal path appears untenable, characterized by ongoing deficits, increasing interest expenses, and political stalemate regarding fiscal reforms, which pose considerable threats to economic stability and undermine global confidence in the creditworthiness of the United States. (See Fig.1).

Political divisions regarding fiscal policy, coupled with ongoing impasses related to the debt ceiling, significantly heighten uncertainty and foster concerns about possible defaults or postponed payments. Such developments could result in downgrades of credit ratings, reminiscent of the 2011 incident when Standard & Poor’s first reduced the U.S. credit rating. Should investors start to doubt the United States’ capacity or willingness to effectively manage its debt, the demand for U.S. Treasury securities may diminish, leading to increased borrowing costs and jeopardizing the stability of global financial markets that depend on U.S. debt as a secure asset. This decline in confidence could initiate a cascading effect, threatening the U.S. dollar’s position as the preeminent global reserve currency.

Make no mistake, if we continue on this path, investors will eventually lose confidence in our debt. The change could be gradual or sudden, but the consequences will be painful, no matter the pace. The federal government’s interest costs, already at $892 billion for 2024, will increase dramatically, as investors demand a higher risk premium. That will force painful tax hikes or spending cuts. Private sector borrowing costs tied to Treasury rates will also spike, damaging economic growth. Banks, managed funds, insurance companies, pensions, and other investors will be exposed to trillions of dollars in market losses as the Treasuries they hold lose value, precipitating widespread distress in our financial system.[3]

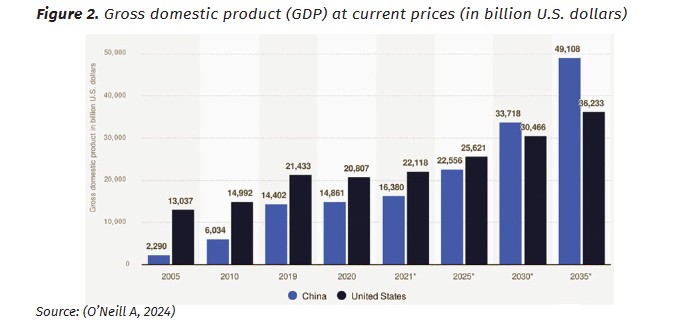

The United States is confronted with significant challenges beyond its sovereign debt, particularly in light of China’s swift economic ascent over recent decades. Once perceived as a distant rival, China’s gross domestic product (GDP) has surged from under 5% of the global total in the 1990s to nearly 18% by 2023, positioning it as a formidable competitor to the United States, whose share has decreased from over 25% to around 22% during the same timeframe. When adjusted for purchasing power parity (PPP), China overtook the U.S. in GDP as early as 2014, indicating a significant reduction in the economic disparity between the two nations. This transformation is indicative of China’s consistent growth, propelled by industrial development, technological progress, and a robust export-oriented strategy, contrasting with the U.S.’s more sluggish growth, which has been hindered by recurrent economic downturns and escalating debt levels. Although the U.S. continues to excel in innovation and per capita GDP, China’s economic rise has altered the global power landscape, posing challenges to U.S. supremacy in trade, investment, and geopolitical influence. (See Fig.2).

Since 1980, US GDP per capita growth has been far below its long-run average, and since 2007, it has been particularly weak. The rate at which the U.S. economy creates value on a per-person basis has ground to a near halt in recent years. From 1929 to 1979, real per capita GDP growth was 2.4% per year. Since then, it has been just 1.7% per year, and the most recent period has been particularly lackluster. From 2007 to 2015, real per capita GDP has been just 1% per year and a meager 1.4% since the nadir of the recession in 2009. To illustrate the problem from another angle, consider that from 1961 to 1981, real annualized growth in GDP per capita never fell below 1.5% over 10 years, and for 16 of the 21 years, 10-year per capita growth exceeded 2% on an annualized basis. Over the next 34 years until 2015, 10-year growth reached 2% only 13 times.[4]

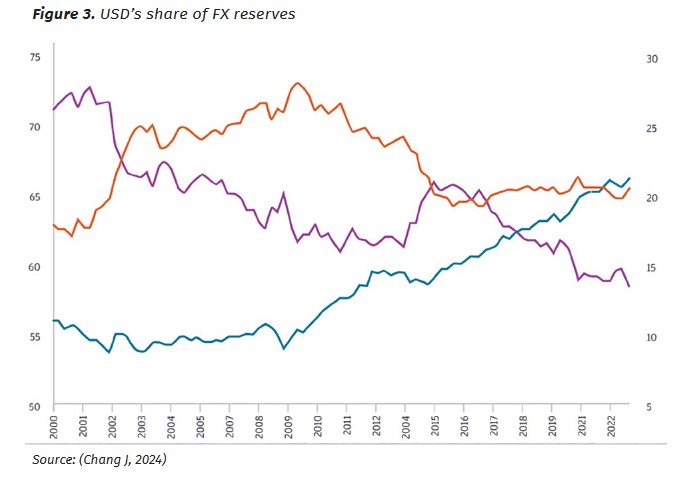

Confidence serves as a fundamental pillar for any global currency, and the supremacy of the U.S. dollar as the preeminent reserve currency is significantly anchored in its perceived stability, liquidity, and dependability. Nevertheless, the escalating use of the dollar as a tool in geopolitical confrontations poses a threat to this confidence and may hasten the pursuit of alternative currencies. The 2022 decision to freeze the reserves of Russia’s central bank in response to the Ukraine crisis raised alarms among other nations, particularly China, regarding the security of their dollar or euro-denominated reserves. Such measures heighten apprehensions that reserve assets could be wielded as instruments of political leverage, leading countries to seek diversification away from dollar assets to mitigate the risk of potential sanctions. This shift is illustrated by initiatives such as China’s advocacy for the yuan in global trade and the endeavors of countries like India, Brazil, and members of the BRICS coalition to investigate alternatives to the dollar. Although the dollar continues to hold a dominant position for the time being, an extended reliance on its weaponization could erode trust in its impartiality, gradually undermining its role as the world’s leading reserve currency and fragmenting the international monetary landscape. (See Fig.3).

Confidence is an indispensable requirement for a currency, and beyond a certain point of weaponization, the US undermines international confidence in the dollar as the world currency and accelerates states’ search for alternatives. The more talk there is of appropriating Russia’s reserves, the more countries like China fear their reserves held in dollars or euros may no longer be safe.[6]

Historically, the international dominance of the dollar, and to a lesser extent the euro, sterling, and yen, was supported by the fact that there existed well-organized markets between many local currencies and only these Big Four currencies. This required those seeking to trade other currency pairs to use the dollar or another member of the Big Four as a vehicle or intermediary currency, requiring the investor to pay an additional transaction cost in the form of a second bid-ask spread. Today, in contrast, there exist direct markets in a larger number of currency pairs in a larger number of financial centers. This is reflected in bid-ask spreads on foreign exchange transactions in nontraditional currencies that differ little from those on the majors. At the same time, central bank reserve managers have become more active in managing the investment tranche of their portfolios, whose magnitude has been growing, while many nontraditional currencies display attractive volatility-adjusted returns compared to their traditional competitors. Together, these factors have made for a shift out of the Big Four currencies (in practice mainly the dollar, which dominates the Big Four share).[8]

Renminbi - opportunities and constraints

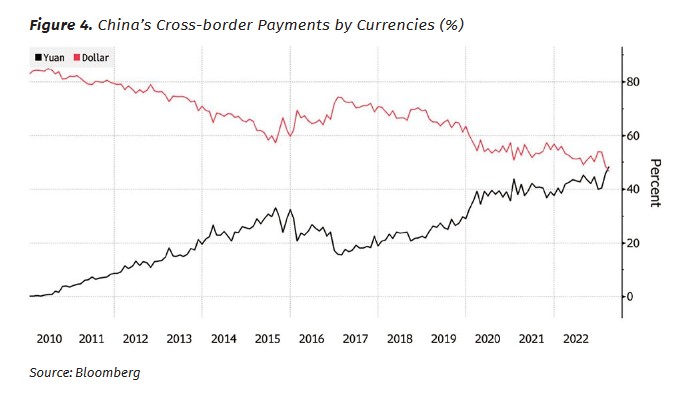

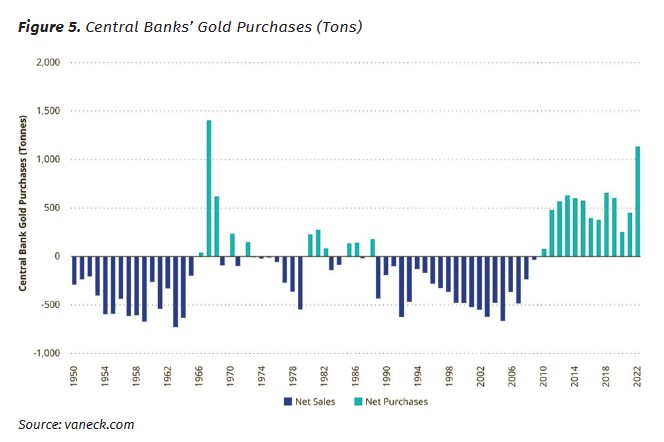

In light of the aforementioned challenges facing the United States and the U.S. dollar, China has been proactively promoting the renminbi (RMB) for cross-border transactions as part of its overarching strategy to internationalize its currency and diminish dependence on the U.S. dollar in international trade. The introduction of the Cross-Border Interbank Payment System (CIPS) in 2015 has significantly improved the efficiency and security of RMB transactions, providing a viable alternative to the SWIFT network. Additionally, China has broadened its network of bilateral currency swap agreements with more than 40 countries, facilitating direct trade settlements in RMB and eliminating the necessity for dollar conversions. This strategy is particularly prominent within the framework of China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), where there is a growing emphasis on RMB-denominated loans and payments. By 2023, the RMB had ascended to become the fifth most utilized currency in global payments, representing over 3% of total transactions, a notable increase from minimal levels a decade prior. China’s commitment to enhancing RMB usage in energy trade, particularly in oil and gas transactions with Russia and Gulf nations, further reinforces this initiative. These endeavors not only advance China’s geopolitical and economic objectives but also mirror a rising inclination among various countries to reduce their reliance on the dollar, particularly in light of increasing apprehensions regarding dollar weaponization and the stability of the global financial system. (See Fig. 5).

In the last ten years, China has introduced strategic policies to establish its network of offshore RMB markets to advance its currency’s global status. These policies include a) the establishment of RMB clearing banks in offshore markets to facilitate settlements of RMB transactions overseas, b) the signing of bilateral RMB currency swap agreements to provide emergency RMB liquidity, and c) the provision of RMB qualified foreign institutional investor (RQFII) quotas that allow investing offshore RMB in China’s onshore bond and equity markets. These arrangements encourage the international use of the RMB and facilitate the development of offshore trading in regional, international, and global settings.[10]

Today, it is beyond dispute that the RMB stands as the greatest potential rival to the U.S. dollar (USD). China’s economic size, prospects for future growth, integration into the global economy, and efforts to internationalize its currency point toward an expanded role for the RMB in international macroeconomics and trade. China’s successes in the realm of financial technology, the rapid adoption of mobile online transactions such as Alipay and WeChat Pay, and its digital currency pilot project are each bridging the gap between today’s USD dominance and a potential RMB-led future.[11]

China’s deficiency in political and judicial transparency significantly hinders the renminbi (RMB) from emerging as the preeminent currency for cross-border payments. The integrity of the global financial system is fundamentally anchored in trust, adherence to the rule of law, and the presence of reliable institutions, all of which are essential for fostering confidence in a reserve currency. Conversely, China’s centralized political framework, coupled with its opaque decision-making and absence of an independent judiciary, discourages foreign investors and trading partners from fully adopting the RMB. The apprehensions surrounding unpredictable regulatory shifts, capital restrictions, and the likelihood of state interference in financial markets contribute to an environment of uncertainty for businesses and governments that hold RMB assets. Additionally, the limited safeguards for property rights and the inconsistent application of contractual obligations exacerbate risks for foreign entities, rendering the RMB a less appealing option as a stable and reliable currency for international trade and reserves. Unless China improves its transparency, fortifies the rule of law, and showcases a commitment to consistent and impartial governance, the RMB’s potential to eclipse the U.S. dollar or euro as the leading cross-border payment currency will remain limited.

Notwithstanding, China is still very much in an intermediate solution to the trilemma. The capital account is still not fully open (strict limits on the flow of capital from China continue), and the authorities still maintain substantial ability to influence the evolution of the exchange rate. This implies that the authorities are trading off some loss of monetary policy autonomy in return for steps that contribute to the greater internationalisation of the RMB. Given the various economic issues facing China currently, this present policy choice of an intermediate policy regime is potentially more attractive than a corner solution of a fully flexible exchange rate and/or a fully open capital account. Moving to either a fully flexible exchange rate and/or a fully open capital account will require policy reforms in other areas, such as further strengthening the financial sector to be able to take on the volatility that inevitably accompanies such regimes.[12]

The notion of establishing a competitive reserve currency system under the leadership of authoritarian regimes presents a philosophical contradiction to the tenets of a rule-based international order. A functional global monetary framework relies on the creation and enforcement of explicit, transparent regulations that oversee financial transactions, currency exchanges, and trade activities. These regulations are intended to foster a stable environment where businesses, governments, and individuals can operate with assurance.[13]

The old-new gold standard

In an era characterized by uncertainty, the likelihood of reinstating the gold standard amid the diminishing supremacy of the U.S. dollar (USD) in international transactions presents a multifaceted challenge shaped by various economic, geopolitical, and institutional dynamics. The USD is increasingly scrutinized due to ongoing inflationary pressures, escalating national debt, and a waning global confidence in its monetary governance. This situation has led to a heightened interest in alternatives such as the Chinese yuan (RMB). Nevertheless, the RMB’s capacity to replace the USD as the leading reserve currency is significantly hindered by China’s authoritarian regime and the perceived inadequacies of its legal and judicial frameworks. These elements pose considerable risks for global investors and erode confidence in the RMB as a reliable and transparent medium for cross-border exchanges. Consequently, the concept of the gold standard has resurfaced in theoretical debates as a potential neutral and apolitical foundation for global monetary systems.

The absence of trust is a grave impediment to any monetary mechanism, whether backed by a rule-based gold standard or a discretionary-based dollar standard. The gold standard is bias-free, under which countries, even with the weakest credit, can achieve financial equality, plus those playing by the rules are rewarded for being trustworthy (and credible).[14]

Central Banks’ Gold Purchases (Tons)

Source: vaneck.com[15]

The significance of a global payment unit, separate from any domestic currency, lies in its capacity to facilitate seamless and effective transactions within the worldwide economy. This particular currency acts as an impartial medium of exchange, unaffected by the economic policies or fluctuations of any individual nation. By providing a shared unit of measurement for international trade and finance, it diminishes transaction expenses, mitigates risks associated with exchange rates, and promotes enhanced transparency and trust in cross-border transactions.[16]

The idea of reinstating the gold standard in light of the diminishing supremacy of the U.S. dollar (USD) is largely unfeasible, especially when considered within the context of the 1945 Bretton Woods agreement. This system was established on the tenets of global collaboration, aimed at ensuring stable exchange rates and enhancing international trade in the wake of World War II. Central to this framework was the establishment of a stable monetary environment where currencies were linked to the USD, which itself was redeemable in gold. This model proved effective as it resonated with the postwar commitment to multilateralism, with nations focusing on shared economic recovery and development rather than individualistic pursuits. In stark contrast, the contemporary global economic landscape is marked by fierce trade conflicts, geopolitical tensions, and a struggle for market supremacy and economic power. Such circumstances erode the essence of international cooperation that underpinned the gold-based monetary system of the mid-20th century. The increasing division among major economies, along with the intricacies of modern financial systems, further reduces the practicality of a gold standard as a basis for international trade.

It remains one of the singular tragedies of modern world economic history that the Bretton Woods system did not come to its final logical maturity. What should have happened as Bretton Woods aged, and as postwar prosperity became an international fixture, is that each successful country should have consistently used a portion of its healthy savings built up during the prosperity to request allotments of gold from the United States, ultimately leave the system, and then establish its currency as directly fixed in gold. The system was primed to do this globally—to effect a return to the classical gold standard—yet this final result never came.[17]

Conclusion

The likelihood of reverting to the gold standard significantly decreases in the face of heightened political tensions and a trade conflict between Western nations and the Global South. The gold standard, along with the Bretton Woods system, relied on international collaboration, mutual trust, and economic agreement—elements that are fundamentally compromised by geopolitical strife and trade disagreements. Trade wars disrupt global trade balances, increase protectionist measures, and intensify distrust among countries, rendering the coordinated monetary policies necessary for a gold standard nearly unattainable. Additionally, the unequal distribution of gold reserves, with affluent Western countries possessing a disproportionate amount, would worsen economic disparities and exacerbate perceptions of financial imperialism, further alienating the Global South. The Bretton Woods Agreement, which linked currencies to the U.S. dollar and indirectly to gold, emerged from post-war unity and cooperative reconstruction efforts, rather than from discord and economic division. Political tensions and trade wars are in direct opposition to the principles of Bretton Woods, making the revival of a gold-backed monetary system not only impractical but also inconsistent with the realities of a divided global economy.

China’s political framework poses a considerable obstacle to the Renminbi (RMB) achieving status as the dominant global reserve currency. Although the RMB has made significant strides towards internationalization, evidenced by initiatives such as the Belt and Road Initiative and its incorporation into the International Monetary Fund’s Special Drawing Rights (SDR) basket, the establishment of a reserve currency necessitates a robust level of transparency, adherence to the rule of law, and an autonomous monetary system. The centralized nature of China’s governance, coupled with the absence of comprehensive capital account liberalization and state oversight of financial markets, diminishes the currency’s attractiveness to international investors. Additionally, apprehensions regarding political influence over economic policies and the opaque decision-making processes of the Chinese Communist Party generate uncertainty among foreign stakeholders. Unless these fundamental challenges are resolved, the RMB’s capacity to supplant the U.S. dollar or the euro as the preeminent global reserve currency will remain limited.

China’s judicial system poses a considerable obstacle to its aspirations of becoming a global financial center that can influence the international stock market similarly to the New York Stock Exchange (NYSE). A strong and unbiased legal framework is essential for fostering investor trust, safeguarding property rights, and effectively resolving disputes—fundamental components of any thriving financial center. Nevertheless, the Chinese judiciary is often viewed as lacking autonomy from political pressures, with courts tending to favor state or party interests over the fair application of the law. This situation generates uncertainty for both foreign and domestic investors, who may be reluctant to fully participate in China’s financial markets. Furthermore, the irregular enforcement of regulations, unclear legal processes, and inadequate protections for shareholder rights further weaken China’s position in establishing itself as a reliable global financial hub. Without significant reforms aimed at improving transparency, consistency, and impartiality within its justice system, China’s financial markets will likely find it challenging to attain the credibility necessary to compete with established global leaders such as the NYSE.

The legal framework must fundamentally guarantee that the rights associated with contracts and property are articulated with clarity and predictability. In the event of a dispute, the parties involved in the contract should ideally refrain from pursuing legal action except as a final measure. Additionally, in cases of litigation, it is essential that the judiciary operates independently, capable of adjudicating claims efficiently and within a reasonable timeframe. Furthermore, once a judgment is rendered, it should be enforced promptly.

The Renminbi (RMB) faces challenges in becoming a leading international reserve currency; however, China’s robust economic performance and its status as a major exporter provide a favorable context for the RMB to emerge as the primary reserve currency within the BRICS coalition. China’s significant role as the principal trading partner for numerous BRICS nations, along with its efforts to diminish dependence on the U.S. dollar through various bilateral trade agreements and the implementation of RMB settlement frameworks, is enhancing the currency’s prominence within this group. Additionally, the shared objective among BRICS nations to lessen their reliance on Western-centric financial systems presents a viable opportunity for the RMB to function as a regional reserve currency, similar to the euro’s role in the European Union. By capitalizing on its economic strength, fostering deeper financial connections within BRICS, and advocating for RMB-centered trade and investment initiatives, China could effectively establish the RMB as a central element of financial interactions among BRICS countries, even if it continues to play a secondary role in the global financial landscape.

Considering the aforementioned factors, it is anticipated that BRICS, akin to Europe, will establish its own de facto intra-bloc reserve currency, with the Renminbi (RMB) assuming a pivotal position in financial transactions among BRICS nations. Nevertheless, on a global scale, the U.S. dollar is projected to maintain its status as the predominant reserve currency, owing to its established advantages, unmatched liquidity, and the robustness of its international financial infrastructure. The dollar’s profound integration into global trade, investment, and payment mechanisms guarantees its sustained importance in cross-border exchanges. Although the ascendance of the RMB within BRICS may pose a regional challenge to the dollar, its overall influence on the USD is expected to be limited, akin to the euro’s impact. Just as the euro emerged as a notable but regionally confined reserve currency without displacing the dollar on a global scale, the RMB is likely to enhance its presence within BRICS while not fundamentally jeopardizing the dollar’s position as the leading global reserve currency.

References:

Aliaga-Díaz, R. (2024). Why the US dollar remains a reserve currency. Vanguard insights, macro-economics. Available at: <https://www.nl.vanguard/professional/insights/macro-economics/why-the-us-dollar-remains-a-reserve-currency-leader> (Last access: 12.07.2024);

Arslanalp, S., Eichengreen, B., Simpson-Bell, C. (2022). The Stealth Erosion of Dollar Dominance: Active Diversifiers and the Rise of Nontraditional Reserve Currencies. International Monetary Fund. Available at: <https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WP/Issues/2022/03/24/The-Stealth-Erosion-of-Dollar-Dominance-Active-Diversifiers-and-the-Rise-of-Nontraditional-515150> (Last access: 12.14.2024);

Bair, Sh. (2024). U.S. Debt Could Drive the Next Financial Crisis. Barron’s Commentary. Available at: <https://www.barrons.com/articles/national-debt-financial-crisis-harris-trump-investors-8608ce19> (Last access: 12.07.2024);

Bloomberg. Youan Overtakes Dollar as China’s Most-used Cross Border Currency. Available at: <https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2023-04-26/yuan-overtakes-dollar-as-china-s-most-used-cross-border-currency> (Last access: 12.14.2024);

Chang, J. (2024). De-dollarization: Is the US dollar losing its dominance? JPMorgan insights. Available at: <https://www.jpmorgan.com/insights/global-research/currencies/de-dollarization> (Last access: 04.01.2025);

Cheung, Y. (2021). The evolution of offshore renminbi trading: 2016 to 2019. Journal of International Money and Finance. Available at: <https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0261560621000188> (Last access 12.14.2024);

Dimitrovic, B. (2012). The Argument for Returning to the Gold Standard: The Lessons of Contemporary History. Free Market Forum. Sam Houston State University. Available at: <https://www.hillsdale.edu/educational-outreach/free-market-forum/2012-archive/the-argument-for-returning-to-the-gold-standard-the-lessons-of-contemporary-history> (Last Access 12.29.2024);

Fiscal Data. Historical Debt Outstanding. Available at: <https://fiscaldata.treasury.gov/datasets/historical-debt-outstanding/historical-debt-outstanding> (Last Access 04.01.2025);

Khidasheli, M. (2024). Triffin Paradox in 21st Century. Economic Profile, Vol. 19, 1(27);

Khidasheli, M. (2024). Monetary Hypocrisy – Case Against the USD Hegemony. Multidisciplinary International Scientific Conference: “Sustainable Development: Modern Trends and Challenges”. Available at: <https://unik.edu.ge/Articles_pdf/78772368a98f32df713e04896c5f478b.pdf#page=9.55> (Last Access 12.29.2024);

Kurien, J. (2020). The Political Economy of International Finance: A Revised Roadmap for Renminbi Internationalization. Yale Journal of International Affairs. Available at: <https://www.yalejournal.org/publications/the-political-economy-of-international-finance-a-revised-roadmap-for-renminbi-internationalization> (Last access: 12.14.2024);

O’Neill, A. (2024). Gross domestic product (GDP) at current prices in China and the United States from 2005 to 2020 with forecasts until 2035. Available at: <https://www.statista.com/statistics/1070632/gross-domestic-product-gdp-china-us/> (Last access: 04.01.2025);

Rothwell, J. (2016). No Recovery: An Analysis of Long-Term U.S. Productivity Decline. Gallup, Inc. Available at: <https://news.gallup.com/reports/198776/no-recovery-analysis-long-term-productivity-decline.aspx> (Last access: 12.07.2024);

Ruijie, Ch. (2022). Renminbi internationalization and trilemma constraints. EAI Working Paper No. 169. Available at: <https://research.nus.edu.sg/eai/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2022/12/EAIWP-No.-169-RMB-Internationalization_Trilemma-Constraints-2.pdf> (Last access: 12.14.2024).

Taskinsoy, J. (2023). Reviving the Gold Standard. University Malaysia Sarawak (UNIMAS). Available at: <https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=4489492> [Last access: 12.29.2024).

VanEck. (2023). Will Investors Follow Central Banks into Gold? Available at: <https://www.vaneck.com/nl/en/blog/gold-investing/joe-foster-will-investors-follow-central-banks-into-gold> (Last Access 04.01.2025);

Wade, H.R. (2024). The beginning of the end for the US dollar’s global dominance. The London School of Economics and Political Science. Available at: <https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/internationaldevelopment/2024/02/29/long-read-the-beginning-of-the-end-for-the-us-dollars-global-dominance/> (Last access: 12.07.2024).

Footnotes

[1] Aliaga-Díaz, R. (2024). Why the US dollar remains a reserve currency. Vanguard insights, macro-economics. Available at: <https://www.nl.vanguard/professional/insights/macro-economics/why-the-us-dollar-remains-a-reserve-currency-leader> (Last access: 12.07.2024).

[2] Fiscal Data. Historical Debt Outstanding. Available at: <https://fiscaldata.treasury.gov/datasets/historical-debt-outstanding/historical-debt-outstanding> (Last Access 04.01.2025).

[3] Bair, Sh. (2024). U.S. Debt Could Drive the Next Financial Crisis. Barron’s Commentary. Available at: <https://www.barrons.com/articles/national-debt-financial-crisis-harris-trump-investors-8608ce19> (Last access: 12.07.2024).

[4] Rothwell, J. (2016). No Recovery: An Analysis of Long-Term U.S. Productivity Decline. Gallup, Inc. Available at: <https://news.gallup.com/reports/198776/no-recovery-analysis-long-term-productivity-decline.aspx> (Last access: 12.07.2024).

[5] O’Neill, A. (2024). Gross domestic product (GDP) at current prices in China and the United States from 2005 to 2020 with forecasts until 2035. Available at: <https://www.statista.com/statistics/1070632/gross-domestic-product-gdp-china-us/> (Last access: 04.01.2025).

[6] Wade, H.R. (2024). The beginning of the end for the US dollar’s global dominance. The London School of Economics and Political Science. Available at: <https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/internationaldevelopment/2024/02/29/long-read-the-beginning-of-the-end-for-the-us-dollars-global-dominance/> (Last access: 12.07.2024).

[7] Chang, J. (2024). De-dollarization: Is the US dollar losing its dominance? JPMorgan insights. Available at: <https://www.jpmorgan.com/insights/global-research/currencies/de-dollarization> (Last access: 04.01.2025).

[8] Arslanalp, S., Eichengreen, B., Simpson-Bell, C. (2022). The Stealth Erosion of Dollar Dominance: Active Diversifiers and the Rise of Nontraditional Reserve Currencies. International Monetary Fund. Available at: <https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WP/Issues/2022/03/24/The-Stealth-Erosion-of-Dollar-Dominance-Active-Diversifiers-and-the-Rise-of-Nontraditional-515150> (Last access: 12.14.2024).

[9] Bloomberg. Youan Overtakes Dollar as China’s Most-used Cross Border Currency. Available at: <https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2023-04-26/yuan-overtakes-dollar-as-china-s-most-used-cross-border-currency> (Last access: 12.14.2024).

[10] Cheung, Y. (2021). The evolution of offshore renminbi trading: 2016 to 2019. Journal of International Money and Finance. Available at: <https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0261560621000188> (Last access 12.14.2024).

[11] Kurien, J. (2020). The Political Economy of International Finance: A Revised Roadmap for Renminbi Internationalization. Yale Journal of International Affairs. Available at: <https://www.yalejournal.org/publications/the-political-economy-of-international-finance-a-revised-roadmap-for-renminbi-internationalization> (Last access: 12.14.2024).

[12] Ruijie, Ch. (2022). Renminbi internationalization and trilemma constraints. EAI Working Paper No. 169. Available at: <https://research.nus.edu.sg/eai/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2022/12/EAIWP-No.-169-RMB-Internationalization_Trilemma-Constraints-2.pdf> (Last access: 12.14.2024).

[13] Khidasheli, M. (2024). Triffin Paradox in 21st Century. Economic Profile, Vol. 19, 1(27).

[14] Taskinsoy, J. (2023). Reviving the Gold Standard. University Malaysia Sarawak (UNIMAS). Available at: <https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=4489492> [Last access: 12.29.2024).

[15] VanEck. (2023). Will Investors Follow Central Banks into Gold? Available at: <https://www.vaneck.com/nl/en/blog/gold-investing/joe-foster-will-investors-follow-central-banks-into-gold> (Last Access 04.01.2025).

[16] Khidasheli, M. (2024). Monetary Hypocrisy – Case Against the USD Hegemony. Multidisciplinary International Scientific Conference: “Sustainable Development: Modern Trends and Challenges”. Available at: <https://unik.edu.ge/Articles_pdf/78772368a98f32df713e04896c5f478b.pdf#page=9.55> (Last Access 12.29.2024).

[17] Dimitrovic, B. (2012). The Argument for Returning to the Gold Standard: The Lessons of Contemporary History. Free Market Forum. Sam Houston State University. Available at: <https://www.hillsdale.edu/educational-outreach/free-market-forum/2012-archive/the-argument-for-returning-to-the-gold-standard-the-lessons-of-contemporary-history> (Last Access 12.29.2024).

Downloads

ჩამოტვირთვები

გამოქვეყნებული

გამოცემა

სექცია

ლიცენზია

ეს ნამუშევარი ლიცენზირებულია Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 საერთაშორისო ლიცენზიით .