International Pilgrimage Tourist Routes and Their Importance in Raising the Country’s Awareness: “The Way of St. Andrew the First-Called”

DOI:

https://doi.org/10.35945/gb.2025.20.004საკვანძო სიტყვები:

Religious tourism, pilgrimage, cultural routes, The Path of St. Andrew the First-Calledანოტაცია

Georgia possesses a unique cultural and historical identity that encompasses a rich variety of cultural values: architectural monuments, folk traditions, music, visual arts, historical-ethnic heritage, and natural landscapes. This combination creates a significant potential for the development of religious tourism. However, unfortunately, only a small portion of this potential has been utilized. The pilgrimage phenomenon is currently experiencing a revival around the world, with long-standing shrines once again attracting seekers of spiritual self-realization. We believe that by adapting global experiences to the Georgian reality and considering current circumstances, it is entirely feasible to establish an international pilgrimage route in Georgia – The Path of St. Andrew the First-Called. This is especially relevant given that St. Andrew traveled multiple times through Georgia and beyond, with this route extending to other countries as well. For the development of religious tourism in Georgia and its popularization in the global tourism market, the most important task is to conduct intensive scientific research on this type of tourism, to create demand through new motivations for tourists, and to provide new products to the market. The work reveals the importance of international pilgrimage tourist routes, the possibility of creating new market niches, and developing new identities. With the correct and well-planned use of modern PR technologies and marketing strategies, in cooperation with international organizations, the Path of St. Andrew the First-Called has great potential as an international pilgrimage route.

Keywords: Religious tourism, pilgrimage, cultural routes, The Path of St. Andrew the First-Called.

Introduction

In the context of modern globalization, no country can achieve successful development without engaging with the global market and coordinating its internal economic and financial policies with regional and global leaders.

The diverse historical experiences of various countries demonstrate that the sustainable development of any state is impossible without active participation in global economic relations. The current level of international labor division has effectively eliminated economic isolation, making it nearly impossible for any country to remain detached from the global economic process.

Modern economies encompass over 50 industries directly linked to tourism, making the synergy effect substantial. Many governments view tourism as a crucial aspect of their policies in the context of economic development. Georgia’s integration into the regional economy and the subsequent growth of its potential and irreversible development largely depend on the advancement of a high-quality and fully developed tourism industry.[1]

Georgia’s strategic objective should be its active participation in the process of globalizing and personalizing international relations. The country must position itself at the center of global economic developments. The full integration of Georgia into the regional economy and its irreversible development will significantly rely on the establishment of a well-developed and high-quality tourism industry.[2]

In the economic structures of developed countries, the service sector dominates. Demand for services is not only economic but also social in nature, impacting material and non-material sectors, as well as culture and the economy.

One of the key components of the service sector is the tourism industry, which has become one of the most widespread global phenomena of the 21st century, affecting all aspects of public life and transforming the surrounding world. In our view, one of the primary factors for Georgia’s integration into the global economy is the development of a comprehensive and high-quality hospitality industry, including tourism, cultural, and religious tourism. Georgia stands out worldwide for its unique and diverse tourism potential.

The Ministry of Economy and Sustainable Development presented a summary report of the results in the tourism and aviation sector in 2023 and held a presentation of the plans for the ongoing year. It was emphasized that the growth and development of these two important sectors of the economy - tourism and aviation - is important for the economy of the whole country in many ways, and most importantly, it generates new jobs and more prosperity for the population. In addition, the Ministry of Economy and Sustainable Development predicts that 2024 will be even more successful, which will be reflected in the 6,8 million passenger flow in the aviation sector and 4,5 billion USD in revenues from tourism.[3]

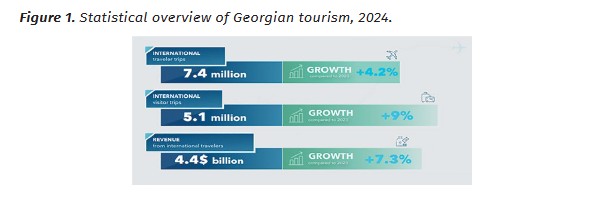

In 2024, Georgia hosted a record number of tourist visits, reaching a historic high of 5,1 million, which represents a 9% increase compared to the previous year. When compared to 2019, the number of tourist visits showed a slight increase of 0,2%. A total of 7 368 149 international travelers visited Georgia in 2024, marking a 4,2% increase over 2023. Compared to 2019, this figure reflects a significant rise of 78,7% (see Figure 1). It is worth noting that last year, the number of tourists from countries such as Israel, the USA, France, the United Arab Emirates, Saudi Arabia, and other countries, whose tourists are distinguished by their purchasing power, reached a record high.[4]

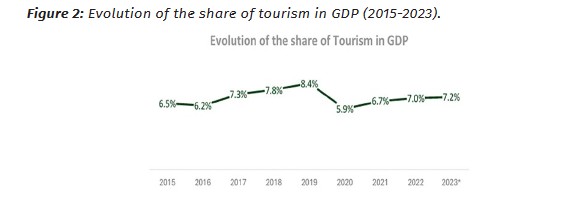

As a result, the added value of tourism-related industries as a share of GDP increased from 6.7% to 7.2% in 2023 (see Figure 2). According to GEOSTAT, the tourism sector contributed 7.2% to the country’s GDP. The increase is 0.5% from 2022 and only 1.2% below 2019.[6]

The figures are interesting in terms of geographical distribution, with 54,6% of visits to the capital Tbilisi, followed by Adjara (40.9%) and Mtskheta-Mtianeti (16.5%). Other regions attracted fewer visitors: Kvemo Kartli (8.7%), Samtskhe-Javakheti (9.6%), Imereti (9%), Kakheti (6.6%), Shida Kartli (3.6%), Samegrelo-Zemo Svaneti (2.7%), Guria (1.4%), and Racha-Lechkhumi, Kvemo Svaneti (0.1%).[8] (see Figure 3).

This data highlights Georgia’s growing role as a significant tourism destination and underscores the need for further strategic development in the sector, particularly in religious and pilgrimage tourism. However, the tourism development objectives outlined in the strategy for 2025 also face some challenges in achievement. Cultural tourism in Georgia faces several challenges. One of the main challenges is the need for sustainable management and preservation of cultural assets in the face of increasing tourism pressure. Striking a balance between heritage conservation and visitor accessibility, and infrastructure development is crucial to ensuring the long-term sustainability of cultural tourism in Georgia. In addition, the development of pilgrimage tourism will contribute to improving the quality of the visitor experience. There is a need to strengthen the capacity of the pilgrimage tourism sector.

Methodology

The study used a systematic review and meta-analysis, quantitative and qualitative research in a systematic review of the development of pilgrimage tourism routes. Sources of evidence were selected, and various designs of studies were used to combine them to obtain a summary conclusion. During the review, peer-reviewed articles were identified around the thematic issue of European pilgrimage tourism routes. We reviewed the documents based on the best pilgrimage routes in relation to the research problem.

Results and discussion

Tourism, like all other human activities, is aimed at satisfying needs as well as fostering spiritual and cultural development. It is an activity through which individuals gain experience in interpersonal relationships. Every form of tourism, even those without specific directions or characteristics, can play a significant role in the development of society and in establishing connections between people of different nationalities, religions, and cultures.

For centuries, religious beliefs have shaped public consciousness and the social organization of individuals and communities. Religion has united people more firmly than racial, national, territorial, or familial ties.

Today, the theme of “Tourism and Religion” has gained significant interest. Around the world, various types of educational tourism, including religious tourism, are increasingly developing. Throughout different historical periods, pilgrimage routes for believers of various religious denominations have included Greece, Egypt, Saudi Arabia, Israel, Palestine, Georgia, Jordan, Italy, India, Tibet, and other destinations.[10]

Religiously motivated travel, such as pilgrimage, is one of the oldest forms of tourism.[11] Barber, in his work “Pilgrims”, explained that Pilgrimage, one of the most widespread religious and cultural phenomena in human society, is an important feature of the major world religions: Christianity, Buddhism, Hinduism, Islam, Judaism, and others. Pilgrimage is defined as “a journey motivated by religious reasons, outwardly to a sacred place and inwardly for spiritual purposes and inner understanding”.[12] “Pilgrimage, the journey to a distant sacred goal, is found in all the great religions of the world. It is a journey both outwards to hallowed places and inwards to spiritual improvement; it can express penance for past evils, or the search for future good; the pilgrim may pursue spiritual ecstasy in the sacred sites of a particular faith, or seek a miracle through the medium of god or a saint. Throughout the world, pilgrims move invisibly in huge numbers among the tourists of today, indistinguishable from them except in purpose”.[13]

Today, pilgrimage is defined differently and can be considered as traditional religious or modern secular travel. The phenomenon of pilgrimage is currently experiencing a revival around the world, with long-standing shrines once again attracting seekers of spiritual self-realization.[14] However, the literature on pilgrimage and religious tourism remains fragmented and lacks synthesis and holistic conceptualization.[15]

The tradition of pilgrimage holds a strong presence in Orthodox Christianity. Pilgrimage was established as a form of religious practice in Christianity from the 4th century. Excursions and pilgrimage journeys occupy an essential place in Christian life. This is due to the long-standing tradition of pilgrimage in Christian culture, as well as the widespread popularity of visiting religious sites among pilgrims.[16]

Among Orthodox countries, Greece, Russia, Romania, and Bulgaria stand out in this regard, as their governments make substantial efforts to develop this sector of tourism. Religious tourism generates economic benefits for local populations, state institutions, tourism organizations, religious establishments, and private entrepreneurs. Notably, in all the aforementioned countries, Georgian churches and monasteries continue to exist and function to this day. The Petritsoni Monastery (Bachkovo Monastery). One of the most prominent Georgian religious sites abroad is the Petritsoni Monastery, also known as the Bachkovo Monastery, the second-largest monastery in Bulgaria after the Rila Monastery. It is located in the Asenovgrad region, 28 km from Plovdiv, on the right bank of the Asenitsa (Chepelarska) River in the Rhodope Valley.

The monastery was founded and built by the Georgian nobleman Gregory Bakurianisdze, a high-ranking military commander at the court of the Byzantine Emperor Alexios I Komnenos and an important political figure of the 11th century. He carefully selected the village of Petritsoni, a land rich in natural blessings, as the site for the monastery. Together with his brother, Gregory built the monastery in 1083, and in 1084, he established its typikon.[17]

The Petritsoni Monastery complex initially comprised three churches: a large cathedral dedicated to the Virgin Mary and two smaller churches dedicated to St. John the Baptist and St. George. Over the centuries, the monastery faced numerous adversities, including a devastating fire in the 15th century that left only the Church of the Archangels intact. Thanks to the efforts of the faithful and donations collected by monks, the monastery was gradually restored between the 16th and 18th centuries.

Today, the Petritsoni Monastery complex consists of residential buildings enclosing the area and is divided into two sections: in the northern courtyard, the Cathedral of the Holy Virgin (18th century) and the Church of the Archangels (12th century) stand, while in the southern courtyard, the Church of St. Nicholas (built between 1834 is located. The residential buildings, which also serve as defensive walls, house the monks’ quarters, guest rooms for pilgrims, and other facilities.

A noteworthy historical figure associated with this monastery is Father Ambrose, the former abbot of the Zographou Monastery on Mount Athos. He once served as a monk at the Bachkovo Monastery and expressed deep reverence for the Catholicos-Patriarch of Georgia, Ilia II, stating, “I believe that we are dealing with one of the greatest patriarchs of all time. Even the most revered elders on Mount Athos were astonished by his wisdom and spirituality. Blessed is the nation that has such a shepherd. I believe that Iberia (Georgia) will shine once again”.[18]

Georgian Religious Heritage Abroad. Georgia’s religious heritage extends beyond the Balkans, with Georgian churches and monasteries found in Romania, Russia, and other regions of the Caucasus.

In Bucharest, on Antim Ivireanul Street (No. 29), stands a beautifully decorated church bearing the name of Antimoz Iverieli, a Georgian cleric and scholar. Built in 1715 with his personal resources, the church features intricate carvings, mosaics, and murals—many of which were crafted by Antimoz himself. Adjacent to the church is the Antimoz Iverieli Museum, which houses an extensive collection of photographs, manuscripts, books, and illustrations documenting his life and work. Antimoz Iverieli dedicated his life to the liberation of Wallachia from Ottoman and Phanariot rule, actively contributing to the construction of over 20 churches and monasteries, the establishment of four printing houses, and the publication of 64 books.

In Russia’s North Caucasus, several historical Georgian churches and monasteries still exist, albeit in various states of preservation. Among them:

- Albi-Yerdi Church (9th–16th century), located in Ingushetia’s Dzheirakh district. It is located in the North Caucasus Federal District, in the Republic of Ingushetia, in the Dzairakh district, on the left bank of the Asa River, in a small Targam cave. Only the ruins of the church have survived to this day.[19]

- Datuna Church, built by Georgian missionaries in the late 10th or early 11th century in present-day Dagestan. The church was built by Georgian missionaries around the end of the 10th century and the beginning of the 11th It was abandoned in the 13th century, although it was still in use for a certain period of the 19th century.[20]

- Senty Church, a 10th-century cathedral in Karachay-Cherkessia, is known for its frescoes.

It was built around the 10th century. The name is thought to be related to the Georgian pillar, Svetitskhoveli. The architectural description of the temple was first given to us by the German scholar Joseph Bernardi in 1829.

- Tkoba-Yerdi Church, an important medieval Georgian church in Ingushetia, is now endangered due to military activity in the region. Tkobaerdi is one of the churches built by Georgian missionaries to promote Christianity among the Vainakh tribes. It was originally a three-nave basilica, typical of medieval Georgian architecture.[21]

Additionally, Georgia has left an enduring legacy on Mount Athos, where the Iviron Monastery (established in the 10th century) became a major center of learning and manuscript translation. During its peak in the 11th century, the monastery played a significant role in preserving Georgian cultural and theological heritage.

The Potential of Religious Tourism in Georgia. Despite its rich religious and historical heritage, Georgia has yet to fully capitalize on its potential in religious tourism. Official statistics show that over the past decade, only 1-2% of international visitors cite religious pilgrimage as their primary reason for traveling to Georgia, while this figure stands at 2-3% among domestic travelers.

However, religious tourism is one of the fastest-growing sectors in global tourism, and Georgia possesses substantial resources to develop it further. The country is home to approximately 12,000 historical and architectural monuments, many of which hold deep religious significance. There is increasing interest from foreign visitors in Georgia’s sacred sites, yet efforts to promote the country as a religious tourism destination remain limited.

Given that 90% of the world’s cultural-historical sites have religious significance, it is essential to recognize the role of religious tourism in society. Identifying and optimizing this sector could enhance Georgia’s position on the global tourism market, stimulate economic growth, and contribute to regional stability.

There is growing discussion about the active manifestation of human interests, particularly towards religion, objects of worship, sacred sites, religious centers, and historical-religious monuments. However, statistical data does not confirm this trend. There are also objective reasons for this, such as the small size of the country, its still-developing economy, and Georgia’s peripheral position within the Christian world. These factors hinder Georgia’s strong penetration and establishment in the global tourism market, including religious tourism. The country requires greater promotion. To achieve this, Georgia must initiate and implement new international pilgrimage routes, which could eventually extend to multiple countries. This would not only enhance the country’s visibility and increase revenues but also contribute significantly to regional stability.[22] In our opinion, the “Route of St. Andrew the First-Called” could play an essential role in this regard.

The Georgian Orthodox Church is an Apostolic Church, meaning that in the first century, Christ’s teachings were preached in Georgia by His apostles. The authenticity of this ecclesiastical tradition is confirmed by both Georgian and foreign written sources, which provide valuable information about the apostles’ activities in Georgia.

In 2001, His Holiness and Beatitude Ilia II, the Catholicos-Patriarch of All Georgia, established the “International Center for Christian Studies” under the Georgian Orthodox Apostolic Church. Based on this foundation, a scientific expedition was formed - “The Research Expedition of St. Andrew the First-Called’s Route”. This scientific expedition examined the path traveled by St. Andrew the First-Called both within Georgia and beyond its borders. Analysis of the expedition’s findings revealed that accounts found in both Georgian and foreign sources regarding St. Andrew’s travels in Georgia - along with the routes, toponymy, and traditions associated with them - often align with the routes traveled and the locations identified during the expedition.[23]

In the village of Didachara, the ruins of a church that, according to tradition, was built by St. Andrew himself, have been preserved to this day. The Georgian Orthodox Apostolic Church commemorates St. Andrew the First-Called twice a year-on May 12 and December 13.

Ancient accounts of St. Andrew’s travels and sermons begin to appear from the 2nd century. Over time, these accounts were supplemented with additional details, expanding the geographical scope of the apostles’ activities. According to the geography of St. Andrew’s journeys, the Holy Apostle visited Georgia three times to preach Christianity. During his third journey, he was accompanied for some time by Simon the Zealot, Matthias, Bartholomew, and Thaddeus. The chronicle The Life of Kartli provides details about this journey.

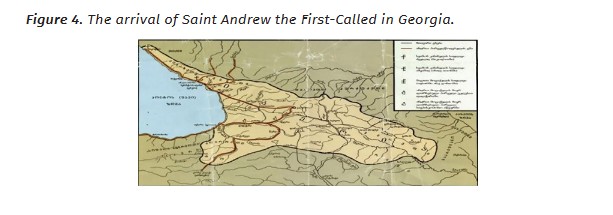

Notably, the route of Apostle Andrew, as recorded by ancient Georgian historians—Trabzon, Apsaros (Gonio), Didachara, Odzrkhe, Atsquri, western Georgia, Tskhum (Sebastopolis), Nikopsia-closely matches a 4th-century Roman road map, which marks international trade routes. Although this map dates to the 4th century, it is largely based on earlier materials from the 1st-2nd centuries.[24] In addition to these regions, Andrew also traveled through Tao and Svaneti, from where he crossed into Ossetia, later returning to Tskhum via Abkhazia. A possible route is illustrated on the (see Figure 4).[25]

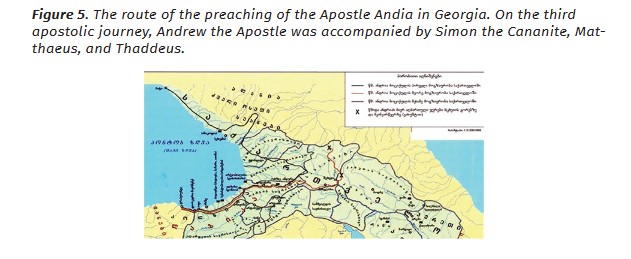

Saint Andrew the Apostle’s route through Georgia can be determined by comparing ancient Georgian sources and old maps (see Figure 5). According to Eusebius of Caesarea, Andrew traveled to Scythia, which, according to the definition of that time, included the lands west, north, and east of the Black Sea. Andrew also visited northern Anatolia, the Caucasus, the Sea of Azov, Crimea, Byzantium, and Greece.[26]

According to J. Chardin and C. Castel, there was an old church named after St. Andrew the Apostle in Bichvinta. There was a cross-shaped column there, before which people knelt and prayed. The activities of Andrew the Apostle in Georgia are emphasized by George of Mtatsminda, George the Less, and Ephrem the Less. The tradition was canonized at the Ruis-Urbnisi Church Council and is recorded in the inscription of this council: “... Andrew the Apostle, brother of his apostle Peter, ascended to us and preached the living sermon of the Gospel to all the lands of Georgia”.[27]

Traditions about St. Andrew the Apostle have been preserved among the people in Didajara, where the ruins of a church have been preserved to this day, which, according to tradition, was built by St. Andrew the First-Called himself. In Samegrelo (Martvili), Samtskhe (Andriatsminda), Kakheti (Martkopi), Khevi (Gergeti). Andrew, who set out from Didajara, had to pass through the villages of Iremadzeebi, Satsikhuri, Agara, Ghorjomi, Tsivtskaro Mountain, Kvabisjvari, and Mamlis Mountain. The ruins of churches on this road are marked on old maps. It is worth noting that the route of the Apostle Andrew, as described by ancient Georgian historians, includes Trabzon, Apsari (Gonio), Didachara, Odzrkhe, Atskuri, Western Georgia, Tskhum (Sebastopolis), Nikopsia...

In order for the Way of St. Andrew to become an international religious tourist route, preparatory work must first be carried out in Georgia, both in terms of the detailed determination and marking of routes, as well as in terms of arranging the infrastructure on this route. In this regard, the presentation of the spatial arrangement of the country presented by the Georgian government gives great hope, where it was stated that “the employment of the population in their native regions should be promoted, tourists should be able to visit all regions without delay, and we should turn all regions of Georgia into four-season resort destinations”.

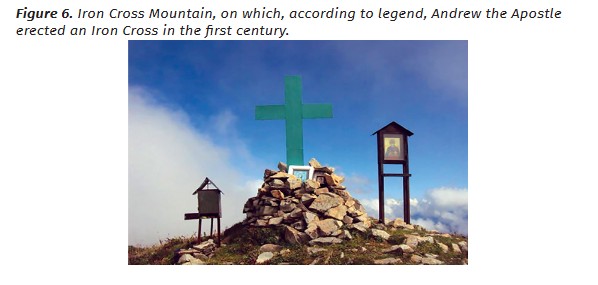

On June 18, 2020, the Ministry of Education, Science, Culture, and Sports of Georgia awarded a certificate to the new cultural route “The Way of St. Andrew the Apostle”. “The Way of St. Andrew the Apostle” is a pilgrimage route, the main theme of which is an excursion pilgrimage trip. Mount Rakminjvari is one of the symbols of the Borjomi-Kharagauli National Park. Its height is 2439 meters above sea level. According to legend, St. Andrew the First-Called erected an iron cross here in the 1st century, which is why the mountain was named Rakminjvari, and the national park’s tourist trail No. 2 is named after St. Andrew the First-Called. Rakminjvari is a favorite place for Orthodox pilgrims and hikers. Figure 6 - shows Borjomi-Kharagauli National Park, Iron Cross Mountain, on which, according to legend, Andrew the First-Called erected an Iron Cross in the first century.[28]

Andrew the Apostle erected an Iron Cross in the first century.[29]

The route, based on materials preserved in Greek-Latin texts and the “Life of Kartli”, introduces us to the path taken by St. Andrew the Apostle in Georgia. At this stage, the route includes several regions of Georgia (Adjara, Imereti, Samtskhe-Javakheti) and 7 different types of objects. The organization presenting the route is the “Academy of Tourism and Management”. This route is included in the first mobile application of Georgian cultural routes, Cultural Routes Georgia. At a later stage, the route can be expanded by involving several regions of Georgia. Among them: Surami, Khashuri, Ulumbo, Mtiuleti, Samachablo, Kutaisi, Samegrelo, Svaneti, Abkhazia.

It should also be noted that Georgia became the 27th member state of the “Council of Europe’s Extended Partnership Agreement on Cultural Routes” in 2016. The Council of Europe’s Cultural Routes programme includes 38 certified routes, crossing 57 countries and over 1,500 cities.[30] Although firms operating in the field of religious tourism have appeared on the Georgian tourism market, the existing potential remains untapped. There are many reasons for this, including underdeveloped infrastructure, lack of information about places of interest, weak ties between local governments and tourism firms, and lack of qualified personnel.

For the development of religious tourism, exhibitions, congresses, and conferences are organized in various countries of the world by religious organizations and associations, as well as by companies interested in the development of the tourism industry. More activity is needed in this regard, both in Georgia and worldwide.

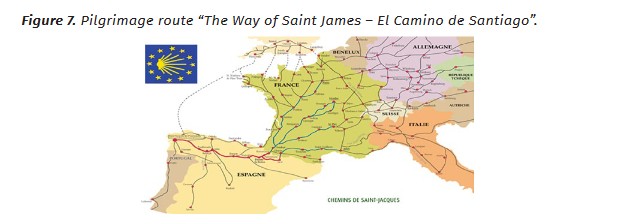

There are many pilgrimage routes in the world, one of the most famous and most famous pilgrimage routes in Europe is the “St. The Way of St. James - El Camino de Santiago”. The Camino de Santiago, translated into English, is The Way of St James. It is an ancient network of walking routes across Europe, called pilgrim routes, that meet at the tomb of St James. Since the 1980s, its popularity has been steadily increasing, and the number of pilgrims in 2013 was more than 200,000. Today, it is second only to Jerusalem and Rome in popularity. The pilgrimage “The Way of St. James – El Camino de Santiago” has become a unique event. For most travelers, it is the cheapest way to relax, a good way to get to know the countries, test your physical endurance (since you will have to walk a large part of the way), and meet interesting people, and pray at the churches and monasteries along the way. Many routes lead to this city (Figure 7).[31]

The main part of the route passes through the Pyrenees in northern Spain. You can start the journey from Spain, France, Germany, Portugal, Great Britain, or any other country. The most popular is the French Way, which is more than 800 km long. To receive a certificate in Latin for completing the Way of St. James, you must register at one of the churches along the way and walk at least 100 km; if you travel by horse, the minimum distance is 150 km, and for a cyclist, 300 km. Each participant in the journey can receive a pilgrim passport, which will contain special stamps that will serve as a document confirming the journey and will give you certain benefits in all hotels, shelters, churches, and monasteries. In every town and almost every village along the entire route, there are special shelters for pilgrims. Most of the shelters are free if you present a pilgrim’s passport. There are also private shelters, where a night’s stay costs 8-12 euros. And there are also municipal shelters, where a night’s stay costs 3-7 euros - this amount is the so-called donation. Those who wish can also stay in three- or four-star hotels.[33]

It is worth noting that the Camino de Santiago is busier during Holy Years. The next Holy Year is 2027. During Holy Years, pilgrims are entitled to a plenary indulgence, the forgiveness of all sins. During these years, the Holy Doors of the Cathedral of Santiago have been open to pilgrims.

The “Way of St. James” has been included in the UNESCO World Heritage List and has been declared a “major cultural heritage of the European route”.

To walk the Camino is a humbling experience. There were many moments when I thought I had bitten off more than I could chew despite vigorous preparation and training. But I trusted that since God permitted me to be there, He would help me accomplish this objective. He did so, and I thank Him.

The walk to Santiago de Compostela in Northern Spain, the Galician region, is something that I will never forget. The shrine is one of the three major shrines of Christendom, along with Rome and Jerusalem. I have had the good fortune to visit all three.[34]

Researchers have interesting ideas about Fisterra as a “new” final destination for pilgrims. They argue that the modern Fisterra as the end of the journey should be seen as both a result of the post-secular trend in Europe and a response to the fact that the historical destination of Santiago de Compostela is increasingly marked by commercialized mass tourism, which is disadvantageous in the context of pilgrimage.[35]

In the article “The Wrong Way: An Alternative Critique of the Camino de Santiago,” the author notes that the 11th-century Camino de Santiago, a spiritual journey to the final resting place of Saint James, has been an important pilgrimage for pilgrims for centuries. Many modern pilgrims try to travel in the same way as in ancient times. However, pilgrims who do not adhere to the perceived “authentic” behavior experience a sense of alienation.[36]

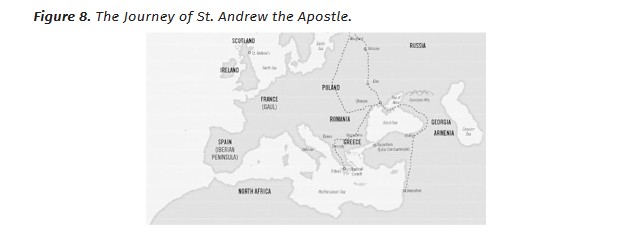

We believe that, if world experience is adapted to Georgian reality and taking into account today’s realities, it is entirely possible to implement an international pilgrimage route “The Way of St. Andrew the Apostle” in Georgia, especially if we take into account that St. Andrew traveled several times and this path passes through other countries besides Georgia (Figure 8). According to our research, the countries where Andrew the Apostle traveled are Israel, Turkey, Russia, Belarus, Ukraine, the Baltic States, Poland, Slovenia, Romania, Moldova, Macedonia, Bulgaria, and Greece.

Conclusion

In our opinion, with the help of correctly and precisely selected and planned modern PR technologies and marketing, in cooperation with international organizations, the international pilgrimage route – “The Way of St. Andrew the Apostle” has great potential.

For the development of religious tourism, we consider close coordination between central and local government bodies – between cultural institutions, healthcare organizations, physical culture and sports, tourism companies, educational institutions, public associations, and religious organizations – essential. This is a complex task, and the state, private, public, and religious institutions should participate in its solution. Only through cooperation will religious tourism have a basis for development and a basis for having a positive impact on cultural and religious dialogue, on the spiritual and economic development of the local population.[38]

To create the desired conditions for the development of religious tourism, it is necessary to:

- form a management mechanism for the development of the tourist direction;

- form a normative-regulatory base for religious tourism to stimulate the mentioned direction and attract investments in this area;

- stimulate business development in the field of religious tourism;

- stimulate the material base for the development of the tourist direction by attracting local and foreign investments - creating new facilities for the preservation and reconstruction of the technical condition of cult architecture as objects of religious tourism;

- create appropriate conditions for the development of tourist zones in the regions of Georgia in the field of tourism; harmonize social and public life, arouse interest in one’s own country, resolve issues related to the preservation of historical and cultural heritage, and protection of environmental conditions;

- create and provide an information system for tourists;

- carry out active advertising and information work, which will be aimed at the tourist image of Georgia and the growth of interest in the religious and cultural values of various confessions;

- improve a full-fledged system for the education and professional training of personnel in the field of religious tourism.

Analysis of the history and current state of the development of religious tourism allows us to draw an important conclusion: as a result of the joint and planned work of state, public, commercial and religious organizations, we can achieve that religious tourism will promote mutual understanding and respect between people from different strata of society and representatives of various traditional confessions, different parts of the country, and different countries. This is on the one hand. In addition, it should be taken into account that today the preservation of traditional values, historical and cultural heritage, and their transfer to future generations is one of the priority tasks, which in many cases cannot be solved without the development of tourism, primarily religious tourism.

References:

Ambioni. Available at: <https://www.ambioni.ge/andriaoba-rkinisjvarze>. (In Georgian);

Barber, R. (1991). Pilgrimages. Boydell Press, Suffolk. Available at: <https://archive.org/details/pilgrimages0000barb>;

Berdzenishvili, D. (2005). Essays. Georgian Historical Monuments Preservation Fund. Available at: <https://dspace.nplg.gov.ge/bitstream/1234/459308/1/Narkvevebi_2005.pdf>. (In Georgian);

Blom, T., Nilsson, M., Santos, X. (2016). The way to Santiago beyond Santiago. Fisterra and the pilgrimage’s post-secular meaning. European Journal of Tourism Research, Vol. 12. <doi.org/10.54055/ejtr.v12i.217>;

Camino Adventures. (2024). The Camino de Santiago Pilgrimage Routes in Spain. Available at: <https://www.caminoadventures.com>;

Collins-Kreiner, N. (2010). Researching Pilgrimage: Continuity and Transformations. Annals of Tourism Research, 32(2). Available at: <https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S016073830900142X?via%3Dihub>;

Digance, J. (2003). Pilgrimage at Contested Sites. Annals of Tourism Research 30(1);

Dvalishvili, G. (2025). Andrew’s Day on the Iron Cross. A public religious online magazine Pulpit. Available at: <https://www.ambioni.ge/andriaoba-rkinisjvarze>. (In Georgian);

Essays on the History of Georgia. (1970). Georgia from Ancient Times to the 4th Century AD, Volume I, Publishing House “Soviet Georgia”. Tbilisi. (In Georgian);

Frank, V. (2013). Your Camino: Santiago de Compostela. Canada. Available at: <https://caminoways.com/your-camino-santiago-de-compostela>;

Georgian National Tourism Administration. (2024). Georgian tourism in figures. Structure & Industry Data. Available at: <https://gnta.ge/en/research/annual-report>;

Georgian National Tourism Administration. (2024). Statistical overview of Georgian tourism report. Available at: <https://api.gnta.ge/storage/files/doc/saqartvelos-turizmis-statistikuri-mimokhilva-2024.pdf>. (In Georgian);

Grdzelishvili, N. (2013). Religious Tourism – as a Factor of Georgia’s Integration into the World and Regional Economy. VII Scientific Conference “Christianity and Economics. State University and the 35th Anniversary of the Enthronement of the Catholicos Patriarch of Georgia, His Holiness Ilia II. Samtavisi and Gori Diocese of the Georgian Patriarchate. (In Georgian);

Grdzelishvili, N. (2015). The factor of religion in the process of forming the tourist brand of Adjara. VIII International Scientific Conference “Christianity and Economics”. Available at: <https://dspace.nplg.gov.ge/handle/1234/487633>. (In Georgian);

Grdzelishvili, N. (2016). Pilgrimage Tourism-St. Andrew’s Way. Spiritual, Social and Economic Aspects. Proceedings of the 9th International Scientific Conference on Christianity and Economics, Kutaisi. (In Georgian);

Grdzelishvili, N. (2018). Religious Tourism. Publishing House “Centaur”, Tbilisi. (In Georgian);

Grdzelishvili, N. (2023). Religious Tourism. Georgian National Academy of Sciences. 978-9941-8-5019-6. Available at: <https://dspace.nplg.gov.ge/handle/1234/540900>. (In Georgian);

Grdzelishvili, N., Gardapkhadze, T. (2020). Factors of Religious Tourism in Georgia and Its Legal Aspects. Proceedings of the Scientific Symposium “Building Peace through Heritage - World Forum for Change through Dialogue”, Florence, March 13-15. Fondazione Romualdo Del Bianco;

International Center for Christian Research under the Georgian Orthodox Church. (2009). In the Footsteps of Andrew the First-Called. Tbilisi;

Jafaridze, A. (2019). Mother Church, Letters and Sermons. The Way of the Apostles. Available at: <https://meufeanania.com>. (In Georgian);

Janashvili, M. (1895). Excellent remains. Iveria Newspaper, N132. Available at: <http://saunje.ge/index.php?id=1684&lang=ru>. (In Georgian);

Kaldani, A. (1988). Christian monuments of Georgian origin in Ingushetia. Magazine “Monument’s Friend”, No. 79. Available at: <http://saunje.ge/index.php?id=1640&lang=en>;

Lange’s Christian Chronicle. (n.d.). Available at: <https://christian-hx.fyi/andrew>;

Metropolitan Ananias. (1991). The Way of the Apostles. Eri Newspaper, 21. VIII. Available at: <http://meufeanania.info/%E1%83%9B%E1%83%9D%E1%83%AA%E1%83%20%98%E1%83%A5%E1%83%A3%E1%83%9A%E1%83%20(bolo%20naxva%>. (In Georgian);

Ministry of Economy and Sustainable Development of Georgia. (2024). Georgia’s Tourism and Aviation Sectors - 2023 Summary Report and 2024 Plans. Available at: <https://www.economy.ge/?page=news&nw=2471&lang=en>;

Ministry of Education, Science and Youth of Georgia. (2020). Cultural Routes Georgia. The first free mobile application for cultural routes. Available at: <https://www.mes.gov.ge/content.php?id=10495&lang=geo>;

Nutsubidze, P., Chanishvili, G. (1993). Datuna Church, Magazine “Monument’s Friend”, No. 1. Available at: <http://www.saunje.ge/index.php?id=1633&lang=ru>. (In Georgian);

Orthodoxy.ge. (n.d.). Foreign fathers on our patriarch. Public Relations Service of the Patriarchate of Georgia. Available at: <https://www.orthodoxy.ge/patriarqi/utskhoelebi.htm>. (In Georgian);

Overall, J. (2019). The Wrong Way: An alternative critique of the Camino de Santiago. European Journal of Tourism Research, Vol. 22. Available at: <https://ejtr.vumk.eu/index.php/about/article/view/375/379>; <doi.org/10.54055/ejtr.v22i.375>;

Patriarchate of Georgia. (2021). Petritsoni Monastery in Bulgaria. Available at: <https://patriarchate.ge/news/1924>;

Pospisil, R. (2014). The Camino De Santiago: Cycling “The Way”. Available at: <https://theprovince.com/travel/camino-de-santiago>;

Rinschede, G. (1992). Forms of religious tourism. Annals of Tourism Research, Vol. 19 (1). Available at: <https://doi.org/10.1016/0160-7383(92)90106-Y>;

The World Bank. (2024). Georgia: Tourism Trends Analysis and Recommendations. Available at: <openknowledge.worldbank.org/server/api/core/bitstreams/7b9b850e-6dd3-42ec-aaca-3a24f47c5c9d/content>;

Timothy, D. J., Olsen, D. H. (2006). Tourism, religion and religious journeys. Routledge, London.

Footnotes

[1] Grdzelishvili, N. (2015). The factor of religion in the process of forming the tourist brand of Adjara. VIII International Scientific Conference “Christianity and Economics”, p. 40-44. Available at: <https://dspace.nplg.gov.ge/handle/1234/487633>.

[2] Grdzelishvili, N. (2013). Religious Tourism – as a Factor of Georgia’s Integration into the World and Regional Economy. VII Scientific Conference “Christianity and Economics, p. 41-48. State University and the 35th Anniversary of the Enthronement of the Catholicos Patriarch of Georgia, His Holiness Ilia II. Samtavisi and Gori Diocese of the Georgian Patriarchate.

[3] Ministry of Economy and Sustainable Development of Georgia. (2024). Georgia’s Tourism and Aviation Sectors - 2023 Summary Report and 2024 Plans. Available at: <https://www.economy.ge/?page=news&nw=2471&lang=en>.

[4] Georgian National Tourism Administration. (2024). Statistical overview of Georgian tourism report. Available at: <https://api.gnta.ge/storage/files/doc/saqartvelos-turizmis-statistikuri-mimokhilva-2024.pdf>.

[5] Ibid.

[6] The World Bank. (2024). Georgia: Tourism Trends Analysis and Recommendations. Available at: <openknowledge.worldbank.org/server/api/core/bitstreams/7b9b850e-6dd3-42ec-aaca-3a24f47c5c9d/content>.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Georgian National Tourism Administration. (2024). Georgian tourism in figures. Structure & Industry Data. Available at: <https://gnta.ge/en/research/annual-report>.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Grdzelishvili, N. (2018). Religious Tourism. Publishing House “Centaur”, Tbilisi.

[11] Rinschede, G. (1992). Forms of religious tourism. Annals of Tourism Research, Vol. 19(1), pp. 51-67. Available at: <https://doi.org/10.1016/0160-7383(92)90106-Y>.

[12] Collins-Kreiner, N. (2010). Researching Pilgrimage: Continuity and Transformations. Annals of Tourism Research, 32(2). Available at: <https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S016073830900142X?via%3Dihub>.

[13] Barber, R. (1991). Pilgrimages. Boydell Press, Suffolk. Available at: <https://archive.org/details/pilgrimages0000barb>.

[14] Digance, J. (2003). Pilgrimage at Contested Sites. Annals of Tourism Research 30(1).

[15] Timothy, D. J., Olsen, D. H. (2006). Tourism, religion and religious journeys. Routledge, London.

[16] Grdzelishvili, N. (2016). Pilgrimage Tourism-St. Andrew’s Way. Spiritual, Social and Economic Aspects. Proceedings of the 9th International Scientific Conference on Christianity and Economics, Kutaisi, pp. 59-64.

[17] Patriarchate of Georgia. (2021). Petritsoni Monastery in Bulgaria. Available at: <https://patriarchate.ge/news/1924>.

[18] Orthodoxy.ge. (n.d.). Foreign fathers on our patriarch. Public Relations Service of the Patriarchate of Georgia. Available at: <https://www.orthodoxy.ge/patriarqi/utskhoelebi.htm>.

[19] Kaldani, A. (1988). Christian monuments of Georgian origin in Ingushetia. Magazine “Monument’s Friend”, No. 79. Available at: <http://saunje.ge/index.php?id=1640&lang=en>.

[20] Nutsubidze, P., Chanishvili, G. (1993). Datuna Church, Magazine “Monument’s Friend”, No. 1, pp. 41-45. Available at: <http://www.saunje.ge/index.php?id=1633&lang=ru>.

[21] Janashvili, M. (1895). Excellent remains. Iveria Newspaper, N132, p. 2. Available at: <http://saunje.ge/index.php?id=1684&lang=ru>.

[22] Grdzelishvili, N. (2023). Religious Tourism. Georgian National Academy of Sciences. 978-9941-8-5019-6. Available at: <https://dspace.nplg.gov.ge/handle/1234/540900>.

[23] International Center for Christian Research under the Georgian Orthodox Church. (2009). In the Footsteps of Andrew the First-Called. Tbilisi.

[24] Essays on the History of Georgia. (1970). Georgia from Ancient Times to the 4th Century AD, Volume I, Publishing House “Soviet Georgia”. Tbilisi.

[25] Metropolitan Ananias. (1991). The Way of the Apostles. Eri Newspaper, 21. VIII. Available at: <http://meufeanania.info/%E1%83%9B%E1%83%9D%E1%83%AA%E1%83%20%98%E1%83%A5%E1%83%A3%E1%83%9A%E1%83%20(bolo%20naxva%>.

[26] Jafaridze, A. (2019). Mother Church, Letters and Sermons. The Way of the Apostles. Available at: <https://meufeanania.com>.

[27] Berdzenishvili, D. (2005). Essays. Georgian Historical Monuments Preservation Fund. Available at: <https://dspace.nplg.gov.ge/bitstream/1234/459308/1/Narkvevebi_2005.pdf>.

[28] Dvalishvili, G. (2025). Andrew’s Day on the Iron Cross. A public religious online magazine Pulpit. Available at: <https://www.ambioni.ge/andriaoba-rkinisjvarze>.

[29] Ambioni. Available at: <https://www.ambioni.ge/andriaoba-rkinisjvarze>.

[30] Ministry of Education, Science and Youth of Georgia. (2020). Cultural Routes Georgia. The first free mobile application for cultural routes. Available at: <https://www.mes.gov.ge/content.php?id=10495&lang=geo>.

[31] Pospisil, R. (2014). The Camino De Santiago: Cycling “The Way”. Available at: <https://theprovince.com/travel/camino-de-santiago>.

[32] Ibid.

[33] Camino Adventures. (2024). The Camino de Santiago Pilgrimage Routes in Spain. Available at: <https://www.caminoadventures.com>.

[34] Frank, V. (2013). Your Camino: Santiago de Compostela. Canada. Available at: <https://caminoways.com/your-camino-santiago-de-compostela>.

[35] Blom, T., Nilsson, M., Santos, X. (2016). The way to Santiago beyond Santiago. Fisterra and the pilgrimage’s post-secular meaning. European Journal of Tourism Research, Vol. 12. <doi.org/10.54055/ejtr.v12i.217>.

[36] Overall, J. (2019). The Wrong Way: An alternative critique of the Camino de Santiago. European Journal of Tourism Research, Vol. 22. Available at: <https://ejtr.vumk.eu/index.php/about/article/view/375/379>; <doi.org/10.54055/ejtr.v22i.375>.

[37] Lange’s Christian Chronicle. (n.d.). Available at: <https://christian-hx.fyi/andrew>.

[38] Grdzelishvili, N., Gardapkhadze, T. (2020). Factors of Religious Tourism in Georgia and Its Legal Aspects. Proceedings of the Scientific Symposium “Building Peace through Heritage - World Forum for Change through Dialogue”, Florence, March 13-15. Fondazione Romualdo Del Bianco, p. 503.

Downloads

ჩამოტვირთვები

გამოქვეყნებული

გამოცემა

სექცია

ლიცენზია

ეს ნამუშევარი ლიცენზირებულია Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 საერთაშორისო ლიცენზიით .