FinTech and Foreign Trade in Algeria: Opportunities, Challenges, and Strategic Imperatives for the Banking Sector

DOI:

https://doi.org/10.35945/gb.2025.20.002საკვანძო სიტყვები:

Financial technology, FinTech, foreign trade, Algerian banks, trade finance, digital transformation, innovation policyანოტაცია

This research explores the impact of FinTech on Algeria’s foreign trade and how the banking sector is adapting to digital innovation. Using a mixed-methods approach integrating statistical data with expert analysis, the study evaluates digital tools’ influence on trade activities. The findings reveal inconsistent progress: while some banks have embraced FinTech, reaping benefits in efficiency, risk management, and compliance, the industry still grapples with outdated infrastructure, regulatory inflexibility, and low digital literacy. However, signs of progress emerge, especially in mobile payments and blockchain technologies.

Drawing on international case studies and regional comparisons with Kenya, India, the UAE, and Brazil, the paper identifies concrete actions to propel Algeria forward through focused investment in digital infrastructure, regulatory reform, and bank-FinTech collaboration. By systematically comparing regional trends and reviewing global implementation experiences, the study proposes specific, time-bound interventions tailored to Algeria’s institutional landscape: a phased investment plan of USD 380-470 million over five years, focused on digital infrastructure upgrade, regulatory reform, strategic alliances with mature FinTech platforms, and structured capacity building.

The study sets concrete goals: cutting transaction times from 5-7 days to 24-48 hours, boosting trade finance digitization from 15-20% to 75%, and extending financial inclusion from 43% to 60% of adults by 2030. The research concludes that greater FinTech adoption in Algeria’s banking and trade sectors could improve competitiveness in global markets, but only with concerted implementation supported by institutional will and resource allocation.

Keywords: Financial technology, FinTech, foreign trade, Algerian banks, trade finance, digital transformation, innovation policy.

Introduction

The rapidly growing field of FinTech has revolutionized finance in new ways, transforming how people conduct business with banks today. More specifically, at the intersection of FinTech and foreign trade, businesses now have new ways to conduct business with other countries that are faster, safer, and more cost-effective. This paper examines the application of FinTech solutions by Algerian banks to enhance their foreign trade techniques, thereby improving the country’s economic growth and competitiveness. The potential of FinTech in Algeria is vast, and this study aims to shed light on its promising future. The paper will examine the specific strategies employed by Algerian banks to identify critical FinTech innovations that are best suited for facilitating cross-border trade. It will also help explore the challenges and opportunities of deploying these technologies and provide a viewpoint regarding their dual development paths.

To guide this investigation, the study addresses the following research questions:

- What specific FinTech solutions have Algerian banks implemented to support their foreign trade operations?

- How have these FinTech solutions influenced efficiency, cost reduction, and risk management in foreign trade processes?

- What are the main barriers and enablers for FinTech adoption in Algeria’s banking sector?

- How can Algerian banks and policymakers leverage FinTech more effectively to improve foreign trade competitiveness and economic growth?

In line with these research questions, the objectives of this study are to:

- Identify and categorize the key FinTech innovations currently used by Algerian banks, particularly in trade finance;

- Evaluate the impact of these technologies on operational performance indicators such as transaction speed, cost-efficiency, and security;

- Examine the institutional and regulatory factors influencing FinTech adoption in Algeria.

By combining regional comparisons, theoretical insights, and a contextualized understanding of the Algerian banking sector, this study aims to contribute to both academic discourse and practical policymaking in the fields of digital finance and international trade.

- FinTech and Trade Transformation

Financial technology (FinTech) represents a paradigm shift in how financial services are developed, delivered, and consumed. At its core, FinTech integrates advanced technologies, including blockchain, artificial intelligence (AI), machine learning, and big data analytics, into traditional banking systems. These technologies disrupt conventional financial operations by offering faster, more secure, and customer-centric services.[1] However, while FinTech has spurred financial inclusion in various global contexts—especially in developing regions where conventional banking systems are underdeveloped—its success is not uniform across different economies. For example, Islamic FinTech has become a niche market that meets the financial needs of people who follow Sharia law. It is growing in countries like Malaysia and the UAE, but it is still underdeveloped in Algeria.[2] The COVID-19 pandemic sped up the use of FinTech around the world, but Algeria’s progress has been much slower, showing that there is still a gap in both infrastructure and institutional readiness. This delay has made people wonder about the structural and policy-based barriers that are holding back digital financial innovation in the country.[3] Adding to this complexity, scholars have debated how much FinTech really makes it easier for everyone to get financial services. Some people say that FinTech makes it easier for people to get involved and lowers the barriers to entry. Critics, on the other hand, warn that FinTech could exacerbate digital divides and increase system vulnerabilities if there is insufficient regulation and infrastructure in place.[4] In Algeria, these worries are especially important because of the lack of regulatory action and the strong hold that state-owned banks have on the market, which together make it harder for the ecosystem to adapt to changes brought about by FinTech. The FinTech landscape is also not the same all over the place. In economies that are digitally advanced, FinTech services cover a wide range of areas, such as neo banking, regtech, digital payments, and investment platforms. In Algeria, on the other hand, FinTech is still mostly limited to mobile payments and basic e-banking services. This difference in the range of technologies used shows that Algeria is not as developed as other countries and shows that it is an important but not well-studied case in the international FinTech conversation. Foreign trade methods have also changed in response to changes in technology and politics, just like FinTech has. Modern trade is based on barter systems and has been shaped by industrialization and colonialism. It now relies heavily on electronic trading platforms, AI-powered risk management tools, and real-time currency analytics.[5] These new ideas are now standard in global trade and are necessary for making things more open, lowering costs, and making them easier to get to. As economies around the world have started to use more digital trade methods, China’s use of digital tools in its Belt and Road Initiative is an example of how big data and AI are used in trade networks to encourage strategic partnerships.[6] Algeria, on the other hand, still uses old systems and manual processes, which makes things less efficient and costs more to run. This omission illustrates a more extensive concern: the lack of a cohesive strategy that amalgamates FinTech with trade modernization and sustainability.[7] This deviation from global standards highlights a significant theoretical deficiency in the literature. Even though trade modernization is seen as important for a country’s competitiveness, there isn’t much research or thought about how digital financial infrastructure—especially in countries like Algeria.[8] Moreover, the intersection between FinTech and foreign trade has emerged as a critical theme in discussions about modern economic transformation. FinTech innovations increasingly play a pivotal role in enhancing the speed, security, and transparency of cross-border transactions. These include improved payment systems, increased access to trade finance, dynamic currency exchange tools, and more efficient supply chain management solutions. While blockchain-based platforms, such as IBM TradeLens and Contour, are now streamlining trade documentation and reducing fraud in many countries, these innovations remain virtually absent in Algeria’s banking sector.[9] At the same time, comparable emerging economies have made more substantial progress. Kenya, for instance, has enabled SME participation in international trade through M-Pesa, while India has simplified cross-border financial access using its Unified Payments Interface (UPI). Both cases illustrate how FinTech can serve as a bridge for financial inclusion and SME empowerment. In Algeria, however, despite facing similar structural challenges, these transformative models have yet to be adopted.[10] Further evidence in the literature highlights how FinTech platforms that utilize alternative data can improve credit assessments and expand access to capital for underserved enterprises.[11] In a country like Algeria, where over half the adult population remains unbanked and SMEs face bureaucratic hurdles in securing trade finance, these digital solutions could offer critical support. However, widespread adoption is hindered by low financial literacy, centralized banking control, and a lack of institutional flexibility. Additionally, FinTech’s potential in enhancing supply chain operations through smart contracts, blockchain, and real-time tracking is widely acknowledged in global trade ecosystems.[12] This study thus fills a critical analytical gap by situating FinTech within the specific financial, policy, and trade ecosystems of Algeria, offering a contextualized perspective on its opportunities and constraints.

- Methodology

This study employs a qualitative, exploratory research design, supported by descriptive and comparative analytical techniques, to investigate the adoption and impact of financial technology (FinTech) on the foreign trade operations of Algerian banks. Given the limited prior empirical research and the early stage of FinTech implementation in Algeria, this approach allows for a deep, contextual understanding of systemic barriers, institutional dynamics, and technological developments. A qualitative framework is particularly suited to examining the layered regulatory, infrastructural, and socio-political dimensions of FinTech in a low-adoption environment. While no primary data were collected, this decision was methodologically deliberate. Due to the nascent and under-documented nature of FinTech in Algeria’s trade finance sector, the study prioritized triangulated secondary data analysis to build a foundational understanding. Additionally, constraints related to access, institutional approvals, and the sensitivity of financial-sector interviews during the research timeline limited the feasibility of primary fieldwork. To offset this, a rigorous multi-source strategy was employed, ensuring analytical depth and reliability.

2.1 Data collection

Data were compiled from multiple authoritative sources to capture a comprehensive view of Algeria’s FinTech landscape, with specific attention to foreign trade practices:

- Academic and Industry Literature: Peer-reviewed journal articles, policy studies, and industry white papers (e.g., World Bank, IMF, Statista) were used to map global and regional FinTech developments and establish theoretical baselines;

- Regulatory and Governmental Documents: Key Algerian legislative texts, central banking decrees, financial sector reform reports, and regulatory guidelines were examined to assess institutional frameworks shaping FinTech integration;

- Quantitative Market and Sectoral Data: Databases providing FinTech usage statistics, mobile penetration metrics, digital transaction trends, and trade finance benchmarks (from both domestic and international sources) were reviewed for contextual comparison and empirical support;

- Case Studies and Institutional Examples: Specific FinTech platforms and financial institutions—such as Yassir, UbexPay, Natixis, and Lloyds Bank—were analyzed to illustrate business models, innovation strategies, and localized applications relevant to the Algerian banking sector.

2.2 Analytical framework

A thematic content analysis was employed to identify and organize key patterns, barriers, and enablers related to FinTech adoption in Algerian foreign trade finance. Data were coded inductively based on recurring concepts and organized around the study’s four core research questions. Thematic categories included technological integration, regulatory dynamics, institutional inertia, and trade facilitation outcomes.

To ensure robustness, the analysis incorporated:

- Triangulation of data types (qualitative themes, quantitative indicators, and legal texts);

- Cross-case comparison with regional and global benchmarks to highlight Algeria’s relative performance and constraints;

- Institutional theory lenses, especially regarding path dependency, bureaucratic rigidity, and market structure influences, to interpret adoption trajectories and policy inertia.

Although manual coding was used, consistency was maintained through repeated review cycles and synthesis matrices that mapped thematic findings against research objectives. This ensured methodological transparency and minimized subjective bias.

2.3 Scope and limitations

This study focuses exclusively on formal banking institutions involved in foreign trade finance in Algeria, with a special emphasis on digital payments, blockchain applications, and AI-powered trade tools. It does not comprehensively cover FinTech developments in insurance, crowdfunding, or cryptocurrency markets, nor does it include informal financial service providers.

Key limitations include:

- No primary fieldwork: Interviews and surveys could have provided stakeholder insights, but were excluded due to access limitations, regulatory sensitivity, and time constraints;

- Reliance on secondary data: Some information may be outdated, incomplete, or subject to institutional bias;

- Contextual specificity: Findings may not be generalizable to other MENA or developing economies without adaptation.

Nonetheless, methodological rigor was maintained through systematic source triangulation, documented coding procedures, and theoretical alignment with current scholarship on FinTech adoption in emerging markets.

2.4 Ethical considerations

This study is based entirely on publicly available secondary data, official documents, and published research. As such, it did not involve human participants and did not require institutional ethical approval.

- Global Perspectives on Fintech in Foreign Trade

To consider how innovation and payment technology (FinTech) could influence the spheres of international trade, examining interesting case studies from various economies is helpful. These are two cases that exemplify how FinTech applications have helped businesses and governments surmount trade restrictions, expand their market presence, and improve efficiency.

3.1 Case studies from leading economies

United Kingdom: Beyond the Bean, a Bristol-based company, leveraged the Lloyds Bank International Trade Portal to expand into international markets. The portal provided essential market insights, economic data, and tools for managing trade documentation, facilitating strategic market entry.

United States: Harlow Group, a metal fabrication firm, utilized Previse’s InstantAdvance to address cash flow issues and secure materials at better prices. This FinTech solution provided critical short-term funding, enabling the company to handle larger orders and improve liquidity.[13]

Brazil: Nubank, a prominent FinTech bank, has significantly expanded financial inclusion, with 46% of Brazil’s adult population using its services. This widespread adoption underscores FinTech’s role in providing accessible financial services.

China: WeBank, China’s digital bank, uses AI to offer efficient banking solutions to SMEs and the broader population. Its online-only model enhances financial accessibility and operational efficiency.[14]

Africa: Mobile money platforms, such as M-Pesa, have transformed financial services across East Africa, North Africa, and South Asia. These platforms offer essential banking services to underserved populations, illustrating the impact of FinTech on financial inclusion.[15]

3.2 Key FinTech Innovations in International Trade

Blockchain Technology: Blockchain offers a secure, decentralized ledger for the real-time tracking of goods and payments, thereby reducing fraud and enhancing transparency in international trade. Smart contracts, coded agreements that execute automatically, streamline trade processes by minimizing the need for intermediaries.

Digital Payment Platforms: FinTech innovations in technology enable real-time, cost-effective transactions that bypass traditional banking inefficiencies. Mobile wallets and currency exchange platforms reduce transaction costs and support global expansion.[16]

Crowdfunding: Crowdfunding platforms enable businesses to raise capital from a diverse group of investors, supporting SMEs in financing export activities and market expansions. This model democratizes access to capital and promotes entrepreneurial growth.[17]

Artificial Intelligence and Big Data: AI and data analytics enhance trade decision-making by predicting trends, optimizing logistics, and improving risk assessments. These technologies help businesses navigate international markets more effectively.[18]

Regulatory Adaptations: Regulatory frameworks are evolving to accommodate FinTech innovations, with sandboxes allowing startups to test new products. This adaptive approach supports FinTech growth while ensuring compliance and consumer protection.[19]

3.3. FinTech worldwide

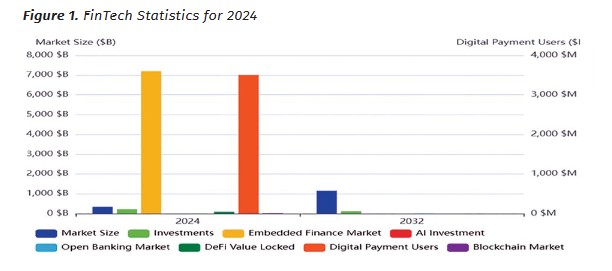

The FinTech industry in 2024 has shown significant growth and transformation across various sectors.

- Market Size and Growth: The FinTech market is expected to exceed $340 billion in 2024, with a projected compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 16.5%, reaching $1,152 billion by 2032.

- Investment Trends: Despite the overall growth, investments in FinTech have declined. In 2021, investments totaled nearly $226 billion, but by 2023, they had decreased to $113.7 billion. This indicates a more selective approach by investors.

- Embedded Finance: Embedded finance integrates financial services into non-financial businesses, representing a rapidly growing trend. The market for embedded finance is expected to reach $7.2 trillion by 2030.

- AI in Personal Finance: AI-powered FinTech startups have seen steady investment growth, from $500 million in 2017 to $2.5 billion in 2023. AI applications in personal finance include budgeting, expense tracking, investment advice, bill payment reminders, and financial planning.

- Central Bank Digital Currencies (CBDCs): Over 130 countries are exploring the development of their digital currencies. CBDCs are expected to create new opportunities for FinTech products and services.

- Open Banking: The open banking market is projected to reach $11.7 billion by 2027, doubling from $5.5 billion in 2023. Open banking enables the secure sharing of customer data through APIs, fostering the development of new FinTech products, such as account aggregators and real-time fraud detection solutions.

- Decentralized Finance (DeFi): Following a decline in investments in DeFi in 2023, an expected resurgence is anticipated in 2024. As of April 2024, the total value locked in DeFi platforms was $86.8 billion.

- Digital Payments: Digital payment users are expected to reach over 3.5 billion by 2024. UPI platforms saw a record 13.4 billion transactions in March 2024.

- Blockchain Technology: Blockchain technology is set to hit $20 billion by 2024. Digital lending through blockchain is projected to rise to $567.3 billion by 2026, with a CAGR of 26.6%.

- Artificial Intelligence: AI will power 95% of all customer interactions within the next decade, with consumers expected to prefer interaction with machines over humans.

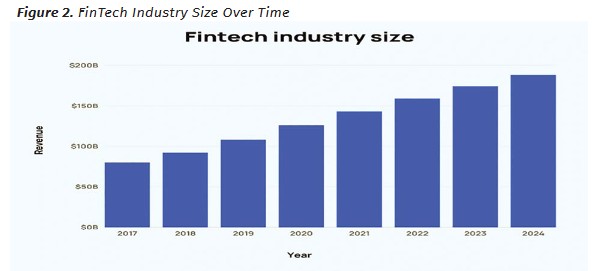

The diagram depicts the upward trend in revenue within the FinTech sector from 2017 to 2024. The graph indicates a steady and considerable rise in revenue throughout the years, highlighting the swift development of the FinTech industry globally.

Primary observations:

- 2017-2020: Consistent growth of the industry; revenues;

- 2021-2022: The growth trend continued, reaching new highs as FinTech adoption accelerated, driven in part by the global shift toward digital solutions during the pandemic;

- 2023-2024 (Projected): The chart projects further revenue increases, indicating that the FinTech industry is expected to surpass $200 billion by 2024.[22]

This growth can be attributed to the increasing digitalization of financial services, the adoption of new technologies such as blockchain and AI, and the global expansion of the FinTech ecosystem. The chart highlights the FinTech sector’s pivotal role in transforming the financial landscape and its potential for sustained growth in the years to come. For countries like Algeria, which remain on the periphery of these developments, the challenge is not only to adopt FinTech solutions but also to adapt them meaningfully within their institutional, regulatory, and economic contexts.

- The Algerian Context

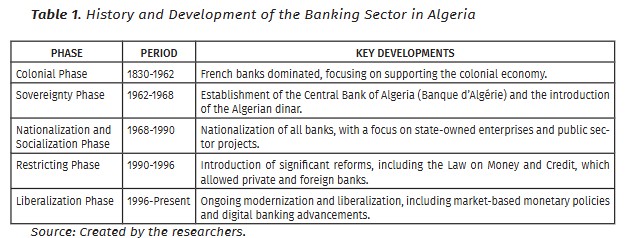

Since gaining independence in 1962, Algeria’s banking sector has undergone significant transformations shaped by political, economic, and regulatory shifts. This evolution can be categorized into distinct phases, each reflecting the broader socio-economic orientation of the state during a specific period. As shown in Table 1, these phases reflect transitions from colonial financial control to sovereign management, socialist consolidation, liberalization, and eventual modernization.

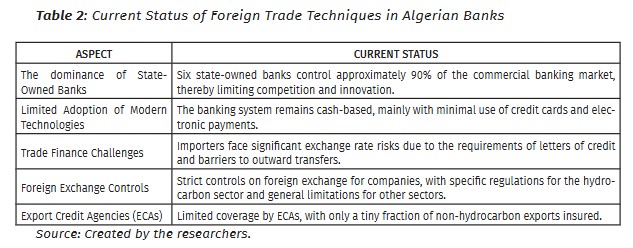

Initially, under French colonial rule, Algeria’s banking system functioned as an extension of French institutions, primarily designed to serve colonial economic interests, particularly those of the agricultural sector. Following independence, Algeria asserted its monetary sovereignty by establishing the Central Bank and introducing the national currency, the dinar. This was followed by a nationalization phase, during which the entire banking sector was brought under state control. The emphasis at the time was on financing state-owned enterprises and public development projects, which marginalized the role of commercial banking. Beginning in the 1990s, Algeria began to move toward liberalization. The 1990 Money and Credit Law marked a turning point by enabling private and foreign banks to operate in the country and granting the Central Bank greater autonomy. However, this phase also generated uncertainty, as liberal reforms clashed with legacy socialist structures. Since 1996, reform efforts have focused on modernizing the banking sector and aligning it with international standards. Market-oriented policies, interest rate deregulation, and the digitization of services have slowly gained traction. As of 2024, Algeria is actively pursuing reforms to enhance its financial stability and improve access to credit, laying the groundwork for greater economic competitiveness.[23] Despite these reforms, the current foreign trade practices within Algerian banks still reflect a hybrid of outdated procedures and nascent digital technologies. Table 2 summarizes the prevailing conditions and challenges faced by the sector.

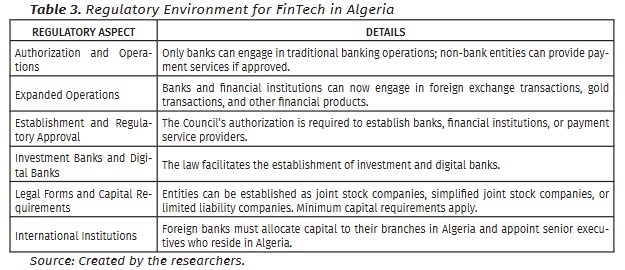

In practice, six central state-owned banks—such as the Banque Extérieure d’Algérie (BEA) and the Banque Nationale d’Algérie (BNA)—dominate the sector, stifling competition and hindering innovation. This lack of diversity in ownership has contributed to the slow adoption of modern financial technologies. The banking infrastructure remains overwhelmingly cash-based, with limited use of credit cards, scarce ATM networks, and underdeveloped digital platforms. Moreover, importers continue to face burdensome requirements such as letters of credit, which expose them to significant exchange rate volatility. Payments to foreign suppliers are typically delayed, and the inefficient domestic transfer system exacerbates transaction costs and delays. Currency control policies also pose challenges. For sectors outside of hydrocarbons, only 50% of export revenues can be retained in U.S. dollars, with the remaining 50% mandatorily converted into the local currency. Exporters within the hydrocarbons sector face even stricter restrictions. Compounding these issues, the role of Export Credit Agencies (ECAs) remains limited. The primary ECA, Compagnie Algérienne d’Assurance et de Garantie des Exportations (CAGEX), provides minimal insurance for non-hydrocarbon exports, limiting support for export diversification.[24] Given this landscape, it becomes clear that structural constraints persist despite policy ambitions. However, recent shifts in Algeria’s regulatory environment suggest emerging opportunities for integrating FinTech. As shown in Table 3, the country has introduced several regulatory updates aimed at fostering innovation while maintaining financial stability.

Key institutions involved in oversight include the Bank of Algeria, the Money and Credit Council, the Banking Commission, and COSOB (the securities market regulator). Foundational regulations such as Banking Law 90-10 and Law №23–09 (passed in June 2023) establish the framework for surveillance and FinTech licensing.[25] Additionally, Executive Decree 20-254 (2020) supports startups by offering incentives and defining legal parameters for innovative ventures.

These regulatory reforms aim to boost financial inclusion by encouraging the development of digital financial services (DFS), including mobile money and e-payments. However, despite regulatory progress, structural barriers persist—most notably, regulatory rigidity, limited digital infrastructure, and low levels of digital literacy. These factors continue to inhibit the scalability of FinTech innovation in Algeria.[26]

In summary, Algeria’s banking and trade finance environment reflects a complex blend of historical legacies, slow-moving reforms, and growing—but constrained—interest in digital innovation. While the institutional landscape is gradually evolving, the challenge remains to accelerate modernization in a way that not only enhances operational efficiency but also promotes inclusivity, competitiveness, and integration with global trade systems.

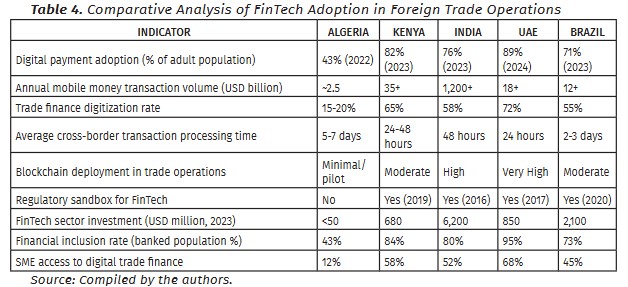

4.1 Comparative positioning: Algeria in the regional and global context

Understanding Algeria’s position requires more than isolated observation—it demands systematic comparison with economies that have faced similar developmental challenges. The countries selected for this analysis share key characteristics with Algeria: predominantly cash-based economies transitioning toward digital finance, significant informal sectors, regulatory frameworks in flux, and ambitions to diversify away from commodity dependence. Yet their trajectories have diverged considerably in recent years, offering instructive contrasts. The following analysis examines five core dimensions: payment digitalization, trade finance modernization, technological infrastructure, regulatory maturity, and financial inclusion outcomes.

This comparison shows differences that are both quantitative and structural. The gap in basic digital payment adoption seems to be getting smaller—Algeria’s 43% is only four decades behind Kenya’s 82%—but the gap in trade finance digitization is a more worrisome story. Algeria’s 15–20% is lower than the UAE’s 72% and lower than economies with similar or lower per capita incomes. Kenya’s experience with M-Pesa shows that infrastructure problems don’t have to be a deal breaker. The platform processes more than $35 billion a year, even though it mostly runs on basic mobile networks. This was possible because of a strategic choice: building on the widespread use of mobile phones instead of waiting for a full banking system to be set up.

India’s path teaches us something else. The Unified Payments Interface (UPI) started in 2016 with clear government support and required banks to take part. Within seven years, it had a transaction volume of $1.2 trillion per year. This wasn’t natural market growth; it was planned policy architecture. The government required interoperability, paid for the first infrastructure costs, and set up legal systems that made it possible for transactions to fail in digital form instead of cash. Algeria’s voluntary adoption model, on the other hand, doesn’t have these forcing mechanisms.

The UAE has a high digitization rate (72%) because the rules are clear and they are enforced. Trade documentation rules clearly favor electronic submissions, processing fees punish transactions done on paper, and government procurement rules require digital payment rails. These aren’t just suggestions; they’re structured incentives with clear results. Algeria’s current system doesn’t have any rewards or punishments that are similar in size.

Brazil’s moderate performance (55%), even though it has problems like Algeria’s, such as geographic dispersion, income inequality, and a fragmented banking sector, suggests that there are possible solutions. The central bank’s PIX project, which started in 2020, made it possible to make free, instant payments without going through commercial banks. In just three years, PIX handled more transactions than all credit cards put together. The lesson is not how advanced the technology is, but how committed the institutions are to getting rid of friction.

In the context of Algeria, three specific gaps need to be addressed. The lack of regulatory sandboxes makes it harder to try out new ideas that might work in a specific area. Second, transaction processing times that are 3 to 7 times longer than those in benchmark countries cost both exporters and importers directly. Third, there is still very little use of blockchain technology, even though there are clear benefits to using it to cut down on fraud. The technology is available, and there are examples of successful use, but uptake is still very low. These are not gaps in knowledge; they are gaps in implementation.

4.2 Lessons from comparative experience: adaptation strategies and pitfalls to avoid

A comparative analysis shows not only where things could be better, but also how to get there, if lessons are adapted instead of copied exactly. What works in one situation might not work in another, but the basic ideas behind it usually still apply. The difficulty is in telling the difference between portable insights and implementations that are specific to a certain situation.

Kenya’s “mobile-first” strategy is worth a lot of thought. Kenyan banks didn’t see sparse branch networks as problems that needed to be fixed at a high cost. Instead, they saw mobile phones as the main way to deliver services. This means that Algeria should focus on integrating mobile wallets with trade finance services instead of opening more branches. A clear goal is to have 15 million mobile banking users by 2028, up from about 8 million now. Agent banking networks, which are retail stores that can do basic banking transactions, can reach areas that don’t have a lot of banks at about one-tenth the cost per transaction of traditional branches. The infrastructure is already there; it just needs to be turned on instead of being built.

India’s requirement that UPI be interoperable gives us a second lesson that can be applied to other situations. The 20 licensed banks in Algeria currently have digital systems that don’t work well together, which means that customers and businesses must keep multiple accounts. By 2027, all licensed banks would have to use compatible APIs, which would eliminate this problem. Data from India shows that these kinds of rules can quadruple the number of transactions in three years, but not by creating new demand; instead, they can do this by removing barriers to existing demand.

Other countries should copy the UAE’s clear rules about when to digitize things. Instead of making vague calls for digital adoption, Emirati regulators set clear goals: By a certain date, half of trade finance would be digitized, and by another date, 75% would be digitized, with clear consequences for those who didn’t comply. This change made digitization a business necessity instead of just an option. Algeria could do something similar, with 50% digitization by 2027 and 75% by 2029. There would be penalties for those who don’t keep up and tax breaks for those who do.

Brazil’s central bank runs an instant payment system called PIX, which is the fourth model. The central bank built infrastructure that all institutions could use on equal terms instead of waiting for commercial banks to work together. A “DinarPay” system run by the central bank and linking all licensed financial institutions could make 2 million transactions happen every day in Algeria by 2028. This solves a problem in Algeria: state-owned banks, which make up the majority of the sector, have little reason to come up with new ideas, and private banks don’t have the size to make big changes. A central platform gets rid of both problems.

Kenya’s slow regulatory process is a warning. For seven years, M-Pesa ran without strict financial rules. When those rules finally caught up, the company had to spend more than $200 million to bring its operations up to code, putting millions of users at risk in the meantime. Before expanding FinTech solutions, Algeria should set up regulatory sandboxes. This means making rules for technologies that haven’t been used yet, which is hard for regulators who like to regulate things they know about, but it’s necessary to stop Kenya’s expensive fixes.

India’s cybersecurity holes during the quick growth of UPI are another warning. Fraud rates were 0.03% of the total number of transactions, which may not seem like a lot, but it added up to hundreds of millions of dollars a year. The rush to grow came before putting money into fraud detection systems. Algeria’s plan should require AI-powered fraud detection and multi-factor authentication from the start. According to the World Bank’s evaluations of similar systems, adding security later costs three to five times as much as building it in from the start.

The UAE’s high implementation costs—about $1.2 billion across the banking sector over five years—are due to the fact that they don’t have any transition periods between top-down mandates. Algeria has a smaller banking sector and stricter budget rules, so it can’t afford to spend as much. A phased voluntary adoption model, with tax breaks for early adopters (like 20% tax credits on FinTech investments for the first three years), would spread the costs over time while keeping the momentum going.

4.3 Algeria-specific limitations

Some problems are unique to Algeria and require a specific approach for resolution. State-owned banks, which control 90% of the commercial banking market, hinder innovation. These organizations don’t have to compete to modernize, and their bureaucratic structures hinder their ability to do so. One potential forcing mechanism is to mandate that 15% of state bank IT budgets be allocated to partnerships with FinTech firms by 2026. This redirects existing resources rather than requiring new appropriations, while creating structured demand for FinTech solutions. Currency controls represent a second Algeria-specific barrier. The requirement to convert 50% of export revenues to local currency deters exporters who face exchange rate volatility. Tunisia’s experience offers relevant evidence: when it relaxed similar controls in 2019, non-hydrocarbon exports increased by 32% over the following three years. The mechanism was straightforward, exporters could price more competitively when they faced less currency risk. Algeria does not need to eliminate controls; allowing 75% USD retention (up from 50%) would partially address the constraint while maintaining capital account oversight.

Infrastructure gaps, while real, are surmountable through hybrid approaches. Roughly 40% of rural areas lack reliable internet connectivity; however, this does not preclude the use of digital financial services. USSD-based services—the technology behind codes like *247# used in Kenya—operate on basic 2G networks and can reach 95% of Algeria’s population with existing telecom infrastructure. These are not ideal long-term solutions, but they enable service expansion while infrastructure catches up.

Financial literacy deficits require direct investment, not just awareness campaigns. Only 31% of Algerian adults report understanding digital banking services, according to World Bank surveys. Morocco’s five-year financial literacy program, which cost approximately $25 million, increased digital banking adoption from 38% to 67% between 2016 and 2021: the program combined school curriculum changes, adult education workshops, and mass media campaigns. Algeria could adapt this model, targeting 5 million adults over three years with a similar investment adjusted for population scale.

- Analysis and Discussion

The current landscape of FinTech in Algeria reveals growing, albeit uneven, adoption among banks. Mobile and digital payment solutions have experienced substantial growth, driven mainly by the COVID-19 pandemic. Banking applications, such as BANXY from Natixis and Barid Pay from Algeria Post, have empowered users to manage accounts, transfer funds, and pay bills directly through their smartphones.[28]

In addition, mobile wallets and peer-to-peer lending platforms are expanding access to financial services, particularly in underbanked rural areas. These digital tools help bridge long-standing service gaps left by conventional banking systems.[29]

This evolving digital shift is further illustrated by Figure 3, which outlines key statistics and projections related to Algeria’s FinTech development.

Available at: <https://www.statista.com/markets/> (Last access: 12.07.2025).

- Digital investment is the most prominent segment, with assets under management (AUM) projected to reach USD 6.02 million in 2024.

- Digital payment users are expected to increase significantly, potentially reaching 21.59 million by 2028.

Such growth signals an increase in public engagement with FinTech platforms, which in turn can enhance Algeria’s international trade operations. FinTech has already demonstrated its role in improving trade efficiency, cost-effectiveness, and security. For instance, the implementation of blockchain technology and artificial intelligence has helped streamline transaction processing and bolster risk management within Algerian banks. Additionally, the growth of digital investments and mobile banking has introduced new tools for compliance and automation in trade finance. However, realizing the full potential of FinTech in Algeria remains constrained by several challenges. These can be broadly categorized into regulatory, infrastructural, and socio-cultural aspects. From a regulatory perspective, although the Algerian government supports FinTech development, the evolving nature of its legal frameworks creates uncertainty for startups and financial institutions. This regulatory ambiguity hinders innovation and deters long-term investment.[30] Furthermore, the country’s limited venture capital ecosystem restricts funding opportunities for promising FinTech ventures. On the infrastructural front, the underdeveloped digital infrastructure in rural areas limits the reach of financial technologies. Although Algeria’s mobile broadband penetration exceeds the MENA average, it remains relatively insufficient to support large-scale digital transformation.[31] Financial literacy deficits and deep-rooted cultural preferences for traditional banking exacerbate these issues. Only 43% of Algerians had a formal banking relationship in 2022, a statistic that highlights the persistent gap in financial inclusion. Moreover, limited financial knowledge and skepticism toward digital platforms pose significant challenges to the widespread adoption of FinTech.[32] Despite these challenges, Algeria’s youthful and tech-savvy population, high mobile penetration rates, and supportive government initiatives offer promising prospects for FinTech innovation. Overcoming these hurdles requires concerted efforts from both the public and private sectors to enhance infrastructure, refine regulatory frameworks, and promote financial literacy. Most innovation in the Algerian FinTech space is found in leading startups such as Yassir and UbexPay. Streamlined regulatory reforms and increasing investments in the sector are likely to propel Algeria into a significant position within the global FinTech stage. The Algerian FinTech sector holds enormous potential for future growth, driven by some critical factors:

The Algerian government’s stance towards FinTech, as evident in various initiatives and regulatory updates, provides a favorable environment for startups to thrive. Ongoing efforts to modernize regulations foster innovation and attract investment. [33] Additionally, Algeria’s young, tech-oriented population and widespread mobile connectivity create a strong demand base for mobile banking and payment solutions. The significant gap in financial inclusion represents both a challenge and an opportunity. With many Algerians unbanked or underbanked, FinTech platforms can play a crucial role in democratizing access to financial services.[34] Digital identity systems already in place can ease onboarding processes and support compliance with anti-money laundering (AML) and know-your-customer (KYC) requirements. Meanwhile, growing adoption of digital payments indicates a market that is gradually embracing financial technology.

Success stories from startups like Yassir, UbexPay, and My-Tree Online highlight Algeria’s innovation potential in this sector.[35] Moreover, several emerging FinTech trends are expected to transform Algeria’s financial landscape further. Islamic FinTech, for example, could provide Sharia-compliant solutions to meet the needs of Algeria’s majority-Muslim population. Open banking also holds promise for promoting competition and interoperability in the financial sector.[36] Closing these gaps in the digital divide and ensuring that investment opportunities remain open is crucial in realizing the full potential of financial technology in Algeria. By grasping these opportunities, Algeria can become a forerunner in FinTech for economic development.[37] The study concludes with the following recommendations for Algerian banks to enhance foreign trade using FinTech:

- Invest in FinTech Infrastructure: Banks should allocate resources to modern technological infrastructure, with a focus on blockchain for secure transactions and AI for risk assessment:

- Form Strategic Partnerships: Collaborating with FinTech companies can help develop specialized solutions for trade finance;

- Develop Customer-Centric Solutions: Banks should implement FinTech solutions that address specific customer needs in foreign trade, such as faster processing and greater transparency;

- Invest in Training: Staff should be provided with training programs to build their capacity and understanding of FinTech applications in foreign trade.

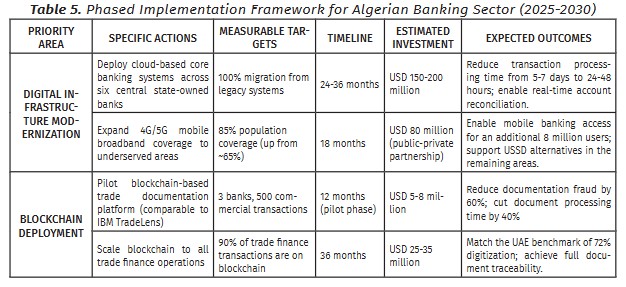

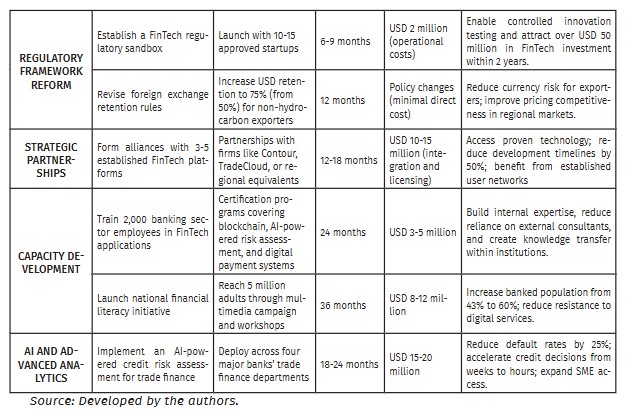

- Strategic Implementation Roadmap: Actionable Recommendations (2025-2030)

Moving from analysis to action requires specificity. Vague exhortations to “invest in infrastructure” or “encourage innovation” offer little practical guidance. What follows is a structured implementation framework built around measurable targets, realistic timelines, and cost estimates derived from comparable deployments in similar economies. These recommendations are not theoretical ideals—they reflect what has worked elsewhere, adapted to Algerian constraints and capabilities.

Investment Phasing and Fiscal Implications:

These investments, although substantial, represent roughly 0.2-0.25% of Algeria’s GDP annually over the five years, comparable to the allocations made by Brazil (0.18% annually) and India (0.22% annually) for similar modernization efforts. The phasing matters as much as the total:

Phase 1 (2025-2026): Foundation Building - USD 180-220 million. Priority is given to infrastructure and regulatory frameworks. The cloud migration of core banking systems and the establishment of a regulatory sandbox create an environment that enables subsequent innovations. This phase focuses on removing constraints rather than deploying solutions.

Phase 2 (2027-2028): Scaling and Integration - USD 120-150 million. With infrastructure in place, this phase scales blockchain deployment beyond pilots and integrates AI-powered systems. The focus shifts from capability-building to operational deployment. Partnership agreements signed in Phase 1 begin generating returns as integrated systems go live.

Phase 3 (2029-2030): Optimization and Expansion - USD 80-100 million. The. The final phase concentrates on refining deployed systems, addressing identified gaps, and expanding successful models. Investments decline as earlier outlays begin generating efficiency savings that partially offset continued modernization costs.

Total Five-Year Investment: USD 380-470 million.

These are not theoretical projections. Brazil’s PIX system cost approximately $40 million to build and generated $200 million in transaction cost savings within three years—a 500% return on investment. India’s UPI investment of roughly $60 million now processes transactions that would cost $3-4 billion annually through traditional banking channels. The economic case does not rest on optimistic assumptions; it relies on documented outcomes from comparable systems.

Critically, these investments require coordination across multiple institutions—the Central Bank, commercial banks, the Ministry of Finance, and regulatory agencies must operate within a unified framework. Nigeria’s failed attempt at similar modernization in the early 2010s saw resource waste exceeding 40% due to uncoordinated initiatives by different agencies. Algeria can avoid this by establishing a centralized implementation authority with clear mandates and promoting cross-institutional participation.

Conclusion

This Study shows the possibilities that FinTech can offer to improve foreign trade techniques in Algerian banking usage. The significant conclusions for this research work are as follows:

- Algerian banks increasingly adopt FinTech solutions, particularly in digital payments and trade finance;

- FinTech has the potential to significantly improve efficiency, reduce costs, and mitigate risks in foreign trade;

- Challenges such as regulatory barriers, infrastructure limitations, and gaps in financial literacy hinder the full potential of FinTech adoption;

- Even though there are problems, there are good chances for growth in the future, such as using new technologies like blockchain and AI.

Strategic Recommendations for Banks to Enhance Foreign Trade Using FinTech:

- Digital Infrastructure: Allocate 2–3% of GDP over five years to invest in digital infrastructure, including payment networks, blockchain platforms, and AI-based risk management systems:

- Financial Inclusion: Increase the share of the population with formal banking access from 43% (2022) to 65% by 2030:

- Cashless Transactions: Target 50% of all transactions to be cashless by 2030, compared to current levels of approximately 30% in Egypt and 36% in Morocco:

- Regulatory Sandbox: Establish a regulatory sandbox by 2026, enabling at least 20 FinTech startups to test innovations annually;

- SME Trade Finance: Double the access of small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) to trade finance by 2028 through digital platforms.

References:

Al Khatib, A. M., Alshaib, B. M., Kanaan, A. (2023). The interaction between financial development and economic growth: A novel application of transfer entropy and a nonlinear approach in Algeria. SAGE Open, 13(4). Available at: <https://doi.org/10.1177/21582440231222980>;

Allen, T., Moen, M., Wohlgenannt, G. (2021). The impact of artificial intelligence on financial services: Innovations and challenges. Journal of Business and Management Studies, 7(4);

Almubarak, S. (2024). Growth opportunities in Algerian FinTech. Economic Development Journal, 5(1);

Bellahcene, A., Latreche, F. (2023). Digital Banking and Financial Inclusion in Algeria. Journal of Digital Finance, 1(2);

Benachour, A., Tarhlissia, L. (2024). The evolution and development of electronic payment in a bank. Case study: CPA-Bank. Financial Markets, Institutions, and Risks, 8(1);

Carè, R., Boitan, I. A., Stoian, A. M., Fatima, R. (2025). Exploring the landscape of financial inclusion through the lens of financial technologies: A review. Finance Research Letters, 72. <doi.org/10.1016/j.frl.2024.106500>;

Chatterjee, S. (2023). Digital payments and global trade. Journal of Economic Integration, 31(1);

Chen, Q. (2024). FinTech innovation in micro and small business financing. International Journal of Global Economics and Management, 2(1);

Dahdal, E. M. (2020). Regulatory sandboxes for FinTech innovation. Regulatory Policy Journal, 15(1);

GSMA. (2024). State of the Industry Report on Mobile Money 2024. London: GSMA Intelligence. Available at: <https://www.gsma.com/mobilefordevelopment/resources/state-of-the-industry-report-on-mobile-money-2024/>;

Hacini, I., Mohammedi, K., Dahou, K. (2022). Determinants of the capital structure of small and medium enterprises: Empirical evidence in the public works and hydraulics sector from Algeria. Small Business International Review, 6(1);

Hamid, A., Widjaja, W. S., Napu, F., Sipayung, B. (2024). The role of FinTech in enhancing financial literacy and inclusive financial management in MSMEs. TECHNOVATE: Journal of Information Technology and Strategic Innovation Management, 1(2);

IMF. International Monetary Fund. (2024). Financial Access Survey 2024: Digital Finance in Emerging Markets. Washington, DC: IMF Statistics Department. Available at: <https://data.imf.org/FAS>;

King, M. R., Osler, C., Rime, D. (2012). Foreign Exchange Market Structure, Players, and Evolution. In: Handbook of exchange rates;

Kumar, N., Kumar, K., Aeron, A., Verre, F. (2025). Blockchain technology in supply chain management: Innovations, applications, and challenges. Telematics and Informatics Reports, 18(2). <doi.org/10.1016/j.teler.2025.100204>.

Liu, W., Dunford, M., Gao, B., Lu, Z. (2018). The Belt and Road Initiative: Reshaping global trade and development. Journal of Contemporary China, 27(112);

Lloyds Bank. (2024). International Trade Portal case studies. Lloyds Bank. Available at: <https://www.lloydsbank.com/business/resource-centre/international-trade-portal.html> (Last Seen: 12.07.2025);

Mansour, R. (2024). Infrastructure limitations in Algeria: A Challenge for FinTech Expansion. North African Economic Review, 10(4);

Meltzer, J. P. (2023). FinTech and international trade: Advancing economic growth through innovation. World Economy, 46(5);

Moro-Visconti, R., Rambaud, S. C., Pascual, J. L. (2020). Sustainability in FinTech: An explanation through business model scalability and market valuation. Sustainability, 12(24), 10316. Available at: <https://doi.org/10.3390/su122410316>;

Musa, B. O. (2022). Effect of financial innovations on financial inclusion: A case of small and medium enterprises in urban informal settlements in Nairobi County. Kenya (Doctoral dissertation, University of Nairobi), University of Nairobi;

Muza, O. (2024). Innovative governance for transformative energy policy in sub-Saharan Africa after COVID-19: Green pathways in Egypt, Nigeria, and South Africa. Heliyon, 10(9). <doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e26600>;

Oguntuase, O. J. (2025). Consumer-focused transition to a bio-based, sustainable economy in Africa. In: Sustainable bioeconomy development in the Global South: Volume I - Status and perspectives, Springer Nature Singapore;

Previse. (2024). InstantAdvance and trade finance. Available at: <https://previse.co/en-gb/success/harlow-group-on-financing-stock/> (Last access: 12.07.2025);

Pu, X., Nguyen, V. (2021). Growth of digital payments in emerging markets: The case of Algeria. Journal of Financial Services and Innovation, 11(3);

Riaz, S. (2023). The Regulatory Environment for FinTech in Algeria: Challenges and Prospects. Journal of Financial Regulation, 8(2);

Saif-Alyousfi, A. Y. (2024). Bank depositors in Arab economies amidst the COVID-19 pandemic. Forum for Economic and Financial Studies, 2(1);

Seddiki, S. (2023). The role of financial technology (FinTech) in overcoming the financing gap for MSMEs in Algeria. El-Bahith Review, 23(1);

Senyo, P. K. (2022). Big data analytics in trade. Trade Analytics Review, 16(1);

Statista. (2024). Industry overview. Available at: <https://www.statista.com/markets/> (Last access: 12.07.2025);

WeBank. (2024). Available at: <https://www.webank.com.tn/fr/> (Last access: 12.07.2025);

Webb, H. C. (2024). Sectoral system of innovation in Islamic FinTech in the UAE’s regulatory sandbox. In: The Palgrave Handbook of FinTech in Africa and the Middle East: Connecting the Dots of a Rapidly Emerging Ecosystem, Singapore: Springer Nature Singapore.

World Bank. (2023). Global Findex Database 2021: Financial Inclusion, Digital Payments, and Resilience in the Age of COVID-19. Washington, DC: World Bank Group. Available at: <https://www.worldbank.org/en/publication/globalfindex>;

Xu, D., Xu, D. (2020). Concealed risks of FinTech and goal-oriented responsive regulation: China’s background and global perspective. Asian Journal of Law and Society, 7(2);

Zhang, B. Z., Ashta, A., Barton, M. E. (2021). Do FinTech and financial incumbents have different experiences and perspectives on adopting artificial intelligence? Strategic Change, 30(3).

Footnotes

[1] Allen, T., Moen, M., Wohlgenannt, G. (2021). The impact of artificial intelligence on financial services: Innovations and challenges. Journal of Business and Management Studies, 7(4), p. 232.

[2] Webb, H. C. (2024). Sectoral system of innovation in Islamic FinTech in the UAE’s regulatory sandbox. In: The Palgrave Handbook of FinTech in Africa and the Middle East: Connecting the Dots of a Rapidly Emerging Ecosystem, Singapore: Springer Nature Singapore, p. 12.

[3] Muza, O. (2024). Innovative governance for transformative energy policy in sub-Saharan Africa after COVID-19: Green pathways in Egypt, Nigeria, and South Africa. Heliyon, 10(9), p. 266. <doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e26600>.

[4] Xu, D., Xu, D. (2020). Concealed risks of FinTech and goal-oriented responsive regulation: China’s background and global perspective. Asian Journal of Law and Society, 7(2), p. 312.

[5] King, M. R., Osler, C., Rime, D. (2012). Foreign Exchange Market Structure, Players, and Evolution. In: Handbook of exchange rates, pp. 1-4.

[6] Liu, W., Dunford, M., Gao, B., Lu, Z. (2018). The Belt and Road Initiative: Reshaping global trade and development. Journal of Contemporary China, 27(112), p. 451.

[7] Oguntuase, O. J. (2025). Consumer-focused transition to a bio-based, sustainable economy in Africa. In: Sustainable bioeconomy development in the Global South: Volume I - Status and perspectives, Springer Nature Singapore, p. 347.

[8] Seddiki, S. (2023). The role of financial technology (FinTech) in overcoming the financing gap for MSMEs in Algeria. El-Bahith Review, 23(1), p. 56.

[9] Carè, R., Boitan, I. A., Stoian, A. M., Fatima, R. (2025). Exploring the landscape of financial inclusion through the lens of financial technologies: A review. Finance Research Letters, 72, p.165. <doi.org/10.1016/j.frl.2024.106500>.

[10] Musa, B. O. (2022). Effect of financial innovations on financial inclusion: A case of small and medium enterprises in urban informal settlements in Nairobi County. Kenya (Doctoral dissertation, University of Nairobi), University of Nairobi, p. 78.

[11] Hamid, A., Widjaja, W. S., Napu, F., Sipayung, B. (2024). The role of FinTech in enhancing financial literacy and inclusive financial management in MSMEs. TECHNOVATE: Journal of Information Technology and Strategic Innovation Management, 1(2), p. 85.

[12] Kumar, N., Kumar, K., Aeron, A., Verre, F. (2025). Blockchain technology in supply chain management: Innovations, applications, and challenges. Telematics and Informatics Reports, 18(2), p. 204. <doi.org/10.1016/j.teler.2025.100204>.

[13] Previse. (2024). InstantAdvance and trade finance. Available at: <https://previse.co/en-gb/success/harlow-group-on-financing-stock/> (Last access: 12.07.2025).

[14] WeBank. (2024). Available at: <https://www.webank.com.tn/fr/> (Last access: 12.07.2025).

[15] Lloyds Bank. (2024). International Trade Portal case studies. Lloyds Bank. Available at: <https://www.lloydsbank.com/business/resource-centre/international-trade-portal.html> (Last Seen: 12.07.2025).

[16] Chatterjee, S. (2023). Digital payments and global trade. Journal of Economic Integration, 31(1), p. 25.

[17] Chen, Q. (2024). FinTech innovation in micro and small business financing. International Journal of Global Economics and Management, 2(1), p. 286.

[18] Senyo, P. K. (2022). Big data analytics in trade. Trade Analytics Review, 16(1), p. 42.

[19] Dahdal, E. M. (2020). Regulatory sandboxes for FinTech innovation. Regulatory Policy Journal, 15(1), pp. 78-95.

[20] Statista. (2024). Industry overview. Available at: <https://www.statista.com/markets/> (Last access: 12.07.2025).

[21] Ibid.

[22] Ibid.

[23] Benachour, A., Tarhlissia, L. (2024). The evolution and development of electronic payment in a bank. Case study: CPA-Bank. Financial Markets, Institutions, and Risks, 8(1), p. 9.

[24] Saif-Alyousfi, A. Y. (2024). Bank depositors in Arab economies amidst the COVID-19 pandemic. Forum for Economic and Financial Studies, 2(1), p. 338.

[25] Al Khatib, A. M., Alshaib, B. M., Kanaan, A. (2023). The interaction between financial development and economic growth: A novel application of transfer entropy and a nonlinear approach in Algeria. SAGE Open, 13(4). Available at: <https://doi.org/10.1177/21582440231222980>.

[26] Hacini, I., Mohammedi, K., Dahou, K. (2022). Determinants of the capital structure of small and medium enterprises: Empirical evidence in the public works and hydraulics sector from Algeria. Small Business International Review, 6(1), p. 13.

[27] World Bank. (2023). Global Findex Database 2021: Financial Inclusion, Digital Payments, and Resilience in the Age of COVID-19. Washington, DC: World Bank Group. Available at: <https://www.worldbank.org/en/publication/globalfindex>; GSMA. (2024). State of the Industry Report on Mobile Money 2024. London: GSMA Intelligence. Available at: <https://www.gsma.com/mobilefordevelopment/resources/state-of-the-industry-report-on-mobile-money-2024/>; IMF. International Monetary Fund. (2024). Financial Access Survey 2024: Digital Finance in Emerging Markets. Washington, DC: IMF Statistics Department. Available at: <https://data.imf.org/FAS>.

[28] Moro-Visconti, R., Rambaud, S. C., Pascual, J. L. (2020). Sustainability in FinTech: An explanation through business model scalability and market valuation. Sustainability, 12(24), 10316. Available at: <https://doi.org/10.3390/su122410316>.

[29] Zhang, B. Z., Ashta, A., Barton, M. E. (2021). Do FinTech and financial incumbents have different experiences and perspectives on adopting artificial intelligence? Strategic Change, 30(3), p. 226.

[30] Mansour, R. (2024). Infrastructure limitations in Algeria: A Challenge for FinTech Expansion. North African Economic Review, 10(4), p. 215.

[31] Riaz, S. (2023). The Regulatory Environment for FinTech in Algeria: Challenges and Prospects. Journal of Financial Regulation, 8(2), p. 85.

[32] Meltzer, J. P. (2023). FinTech and international trade: Advancing economic growth through innovation. World Economy, 46(5), p. 1030.

[33] Bellahcene, A., Latreche, F. (2023). Digital Banking and Financial Inclusion in Algeria. Journal of Digital Finance, 1(2), p. 8.

[34] Almubarak, S. (2024). Growth opportunities in Algerian FinTech. Economic Development Journal, 5(1), p. 12.

[35] Pu, X., Nguyen, V. (2021). Growth of digital payments in emerging markets: The case of Algeria. Journal of Financial Services and Innovation, 11(3), p. 140.

[36] Almubarak, S. (2024). Ibid., p. 13.

[37] Benachour, A., Tarhlissia, L. op-cit, p. 11.

Downloads

ჩამოტვირთვები

გამოქვეყნებული

გამოცემა

სექცია

ლიცენზია

ეს ნამუშევარი ლიცენზირებულია Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 საერთაშორისო ლიცენზიით .