Globalization’s Double-Edged Sword: Resource Dependency and Geo-Politics of Oil in Petróleos de Venezuela (PDVSA)

DOI:

https://doi.org/10.35945/gb.2025.19.010Keywords:

Embedded autonomy, resource nationalism, state-owned oil company, rentier socialismAbstract

Combining institutional theory of the firm with resource dependency analysis, this study explores the ever-changing geopolitics of oil and challenges of overproduction in Venezuela’s national oil company (NOC), PDVSA. It analyzes a state company's structural crisis and its limitations for growth through the lens of resource dependency theory and geopolitics of oil. Despite the recent easing of US sanctions, our findings suggest that an alternative firm strategy is rarely, if ever, viable for the company due to its international and geopolitical dependency. This paper further argues that PDVSA’s performance reflects greater alignment of crisis management with the geopolitics of resource-based development. PDVSA has pursued a strategy of ‘jockeying’ between transnational oil interests (privately-owned, Western MNEs) and non-Western oil companies from allied nations like Russia and China. Furthermore, since much of the oil windfall resulted from currency overvaluation by inefficient national and foreign capital, PDVSA has been unable to maintain a competitive advantage that could enhance its performance. This study is limited to the oil sector in Latin America, but a few examples of ‘resource nationalism’ emerging from other countries are briefly discussed. The paper concludes by discussing the policy implications of the research for oil industry managers in the context of ongoing globalization.

Keywords: Embedded autonomy, resource nationalism, state-owned oil company, rentier socialism

Introduction

This paper examines the evolving corporate performance and crisis of Venezuela’s state-owned oil company, PDVSA, from early 2000 up to the present. Venezuela suffered an unprecedented economic collapse, most intensified by the 2017 debt default and the COVID-19 pandemic most recently. From 2013 to 2018, GDP contracted by a cumulative 47.8 percent, with inflation reaching 130,060.2 percent in 2018.[1] As oil production consistently fell for more than a decade, it collapsed after 2016, forcing President Nicolás Maduro to seek a restructuring of sovereign debt and to renegotiate oil contracts. From 2017 to 2022, disruptions in oil shipments, a declining workforce, and US sanctions on crude oil exports occurred.

With the Nationalization Law of 1976, former President Carlos Andres Perez created PDVSA (Petroleos de Venezuela, S.A.)—the state-owned oil and natural gas company and a holding company for the oil industry that was initially structured to run as a corporation with minimal government interference. Elected in 1998 on a populist authoritarian platform, President Chavez extended direct state control over PDVSA, also to align its governance with his ‘symbolic nation-building project’ called the Bolivarian Revolution.[2] Today, as the largest employer in Venezuela, PDVSA “accounts for a significant share of the country’s gross domestic product (GDP), government revenue, and export earnings”.[3]

Scholarly interest in NOCs has increased in recent years due to a global commodity boom (2000-2004) and the resurgence of ‘resource nationalism’[4] in different parts of the world. For Venezuela, in addition to resource dependency, fiscal over-reliance on oil makes PDVSA highly relevant for discussions[5] on ‘rent capitalism’, ‘rentier socialism’, ‘resource nationalism’, ‘extractive institutions’, ‘rentier state’, or even a ‘petrostate’. These models define the ‘paradox of plenty’[6] as a condition in which developing countries become overly dependent on oil and gas production. This form of dependency leads to potential economic windfalls that typically contribute between one-third and one-half of their GDP.[7] Natural resource-based development, however, is not unique to Venezuela. In most rentier states based on oil, economists point to a ‘resource curse’ that is associated with poor economic growth, lack of democratic institutions, and a weak domestic productive sector.[8] Resource-based development is characterized by highly volatile revenue. Due to a narrow tax base, the government enjoys absolute freedom and has an active role in oil production, a feature less typical of more diversified economies.[9] Being the main distributor of wealth with a monopoly on oil and direct control of the oil industry, the government encounters fewer market pressures to guide the administration of oil wealth.

This study examines the multitude of stakeholders that constitute oil policy-making in PDVSA. After deconstructing the rentier oil strategy as outlined below, it analyzes how the key institutional stakeholders (national government, international oil companies, and their respective governments) have shaped PDVSA’s corporate strategy and performance over time. In our analysis, we draw on the institutional theory of the firm and consider the fragmented and opportunistic nature of the rent distribution system in the global oil market.[10] This paper argues that PDVSA’s performance reflects greater alignment of crisis management with the geopolitics of resource-based development. Against the backdrop of resource dependency and loss of oil rent since 2016, PDVSA has pursued a strategy of ‘jockeying’ between transnational oil interests (privately-owned, Western MNEs) and non-Western oil companies from allied nations like Russia and China. Furthermore, since much of the oil windfall resulted from currency overvaluation by both inefficient foreign and national capital,[11] PDVSA has been unable to maintain a competitive advantage that could enhance its performance. PDVSA’s ties with China and Russia extend beyond mere financial support, they are also influenced by hostile relations with the US. Despite China’s increasing control of the global oil market, North America remains the top destination for PDVSA’s crude oil exports. The U.S. is the dominant player as the main creditor and investor in the international oil market. Using a case study of Venezuela’s national oil company in crisis, this study aims to explore the interaction between firm strategy and evolving geopolitics of oil in natural resource-dependent economies.

- Literature Review: Oil Industry and Natural Resource Dependency

The research on rentier states originates from ‘resource curse’ analysis[12] and ‘paradox of plenty’.[13] These models refer to a problem of over-relying on oil and gas reserves as a potential source of commodity windfalls for developing countries. Mahdavy, who gave the rentier state its contemporary meaning, defined the rentier state as one that relies almost exclusively on the export of raw materials such as oil, gas, or minerals. This includes nations that are financially weak but well-endowed in natural resources.[14] The term ‘external rent’ is used to designate the financial proceeds from sales of the commodity to foreign companies or governments, as opposed to the profits generated typically by manufacturing or productive economic sectors. The extent of this reliance is such that it generates harmful outcomes for development, such as poor economic growth, a weak domestic productive sector, endemic corruption, weak property rights, and unequal distribution of wealth.[15] While the rentier model is common in the Arab world, states that depend on exporting petroleum and distributing its windfall also include Venezuela, Nigeria, Indonesia, Botswana, and Russia.[16]

NOCs serve crucial policy functions for rentier states. They secure a ‘ruling bargain’[17] between political elites and society based on concessions in exchange for populist economic policies. In this framework, public officials secure regime legitimacy through forming loyal constituencies (‘patron-client networks’) that support the petrostate in return for a portion of oil income captured by NOCs.[18] This analysis is pertinent to NOCs that operate as state monopolies in markets with imperfect competition and direct access to economic rent (above-normal profits). While some of these nations do have substantial financial assets, such as Saudi Arabia and Qatar, most are barely capable of funding development in profit-generating, labor-intensive enterprises. Therefore, they do not have a strong domestic productive sector. Venezuela is not even the most extreme example of dependency. Angola and other African petroleum exporting nations are even more vulnerable to the boom-and-bust cycles of the global oil market.

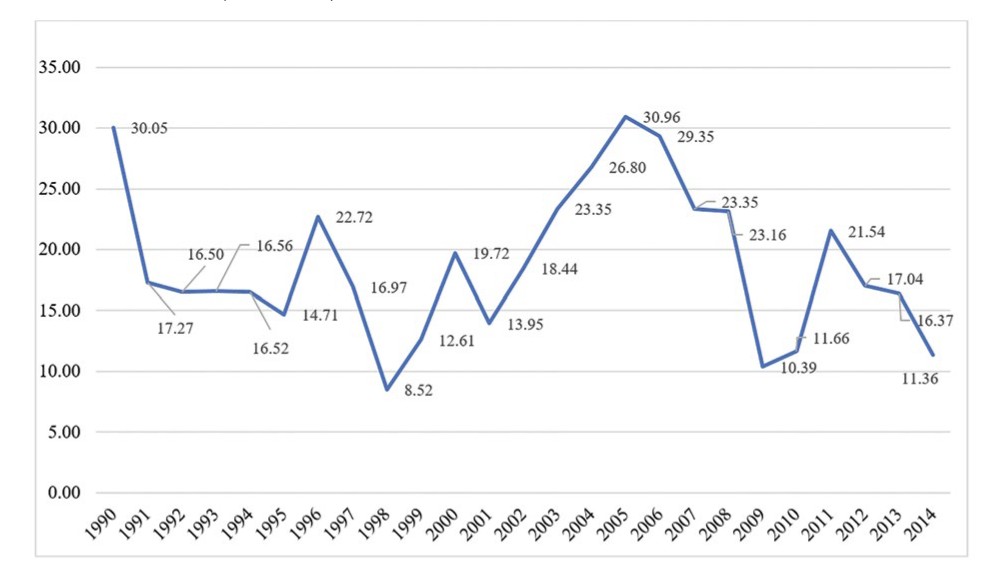

FIGURE 1. VENEZUELA: PETROLEUM INDUSTRY AS SHARE OF EXPORTS %

Source: Figure is the author’s own. Data from UN Comtrade, The Observatory of Economic Complexity (2021), via Statista - The Statistics Portal

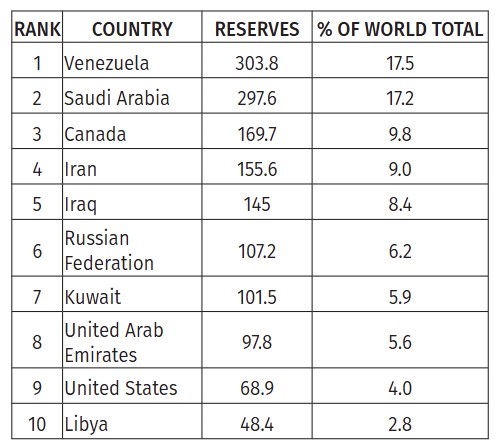

FIGURE 2. OIL RENTS (% OF GDP)

Source: Figure is the author’s own. Data from World Bank (2022), World Development Indicators database

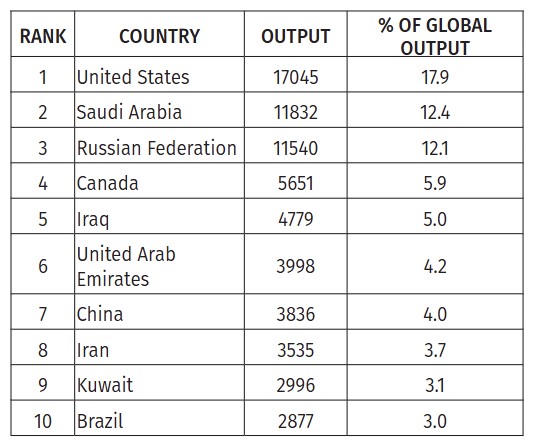

Table 1. Top ten countries with the largest oil reserves in 2019 (thousand million barrels)

Source: Table is the author’s own. Data from BP Statistical Review of World Energy (2020), p. 14.

PDVSA stands out as the quintessential example of a rentier oil company. Venezuela’s supply of oil is substantial, compared to both the size of its economy and most other countries.[19] In 2019, crude petroleum accounted for 83.1 percent of the value of Venezuelan exports. The industry represented 88.3 percent of all export earnings, including refined petroleum, with the highest contribution made in 2013, at nearly 96 percent (Figure 1). Figure 2 displays Venezuela’s oil rents as a percentage of GDP in 1990-2014, starting with the oil opening of the 1990s. Table 1 shows the top ten countries with the largest oil reserves in 2019. Table 2 shows the largest oil producers in 2019. The Orinoco Belt is by far the largest and remaining source of oil in Venezuela, with a reputation for largest extra-heavy oil deposit in the world. Compared to lighter oil, extra-heavy oil consumes more water and energy, is costly to produce, and generates higher mineral pollution and other waste by-products.[20]

Table 2. The top ten largest oil-producing countries in 2019 (thousands of barrels per day, b/d)

Source: Table is the author’s own. Data from BP Statistical Review of World Energy (2020), p.16.

- Theoretical Argument: The Government-Business Relations

Given Venezuela’s over-reliance on oil income, it is imperative to understand the geopolitics of oil and the multitude of stakeholders interacting with the state oil company. As summarized above, the rentier theory predominantly focuses on the national government (‘rent-seeking elites’) and tends to disregard other stakeholders, especially transnational, and their institutional environments that might shape the dynamics of resource dependency. The political capture argument is implicitly deterministic in that it does not consider the potential conflicts of interest or, inversely, mutual dependency between the government and business relations. Various stakeholders—NOC, national authorities, private multinational firms, and their home and host governments—actively shape how the government extracts oil income. Other studies of government interventions in NOCs have analyzed the outcomes, considering the factors of capital intensity, cost structure, and risk exposure in the oil industry. Rather than simply reacting to national interests, Noreng[21] suggests that senior executives of NOCs actively strive for independence from their governments’ resource dependency analysis; however, it doesn’t sufficiently explore how rent-seeking politicians are limited in their ability to continually capture or influence oil policy.[22]

Furthermore, NOCs are unique economic structures. Their decision-making depends on the inherent risks involved in the oil sector, such as geological uncertainty, price volatility, and geopolitical factors. These factors limit government control over oil. Furthermore, exploration, extraction, transportation, and refining affect the cost structure of firms. The global oil market dynamics, including supply and demand, global competition, and the influence of organizations like OPEC, constantly interact with government influence on NOC. In this regard, this paper follows Singh and Chen in viewing NOCs as “complex organizations that bear new developmental capacities rather than vessels of rent-seeking interest”.[23] Originating in Evans,[24] our view of the NOC aligns with the institutional theory of the firm as having an ‘embedded autonomy’ (EA) in the local and institutional environment of the global oil market. According to Styhre, EA implies that modern corporation is embedded in a variety of social practices and stakeholders that are “simultaneously anchored in, for example, corporate legislation and regulatory practices, on the national, regional… and transnational levels, while at the same time being granted the right to operate with significant degrees of freedom within legal-regulatory model”.[25]

The institutional theory of the firm provides a dynamic and contextual framework for understanding the corporate strategies followed by NOCs in various contexts or in different periods in time. It highlights the dynamic interaction in the local and international environments—both the mutually dependent and contradictory relations between the economy, firm, and their state owners. As exemplified by PDVSA, most National Oil Companies (NOCs) are “legally independent firms with direct ownership by the state”,[26] which often leads to highly restricted management autonomy. However, how much the NOC depends on the global economy can also play a significant role in its independence from the government. The nature of global political landscapes determines the modalities of interaction between NOCs and the destinations of their FDI, as well as their engagement with home and host state authorities.

Synthesizing the institutionalist analysis presented above with the geopolitics of power, this paper advances the following argument: PDVSA’s corporate strategy has been shaped by its dynamic relationships within the local institutional environment, global conditions, and the company’s investment strategy, all within the framework of its long-standing reliance on the U.S., particularly the North American oil market. This has led to a persistent crisis for the company, reflecting the ever-changing geopolitics of oil and the challenges of overproduction in a resource-dependent economy.

- Institutional Stakeholders: Government as ‘Sole Owner’

Since the onset of Chavista administration in 1999, PDVSA has been instrumental in channeling the oil wealth to support both the Venezuelan Treasury and the public.[27] Rosales refers to Venezuela as an “example of a neo-extractivist country that pursues a developmental model based on wealth redistribution sustained by oil rents”.[28] As stated in its original governance (Nationalization Law of 1976), PDVSA is fully owned by the government, which controls all the company’s shares. PDVSA’s common stock is not publicly traded; “Pursuant to Article 303 of the Venezuelan Constitution”, the company’s “shares may not be transferred or encumbered”.[29] Since the oil industry generates a substantial portion of foreign exchange and funds the state budget, it would have been impossible to import the goods necessary to satisfy the population’s basic needs without oil income. After benefiting from the commodity boom during the 2000s, Venezuela used the oil windfall to advance ‘economic populism’, i.e., prioritizing social programs and expanding direct government subsidies for energy and food through PDVSA, which provided oil at lower prices to the domestic market. While other presidents also used PDVSA as a political tool to subsidize domestic consumption, Chavez substantially increased debt as a share of GDP by taking on debt and printing money.[30] The state not only used oil to buy influence abroad through the Petrocaribe alliance, but also to secure legitimacy at home by redistributing income directly with revenues from PDVSA.

Oil strategy remained pivotal to ‘nationalist reform policy’, particularly as oil prices began to rise in the early 2000s. According to Lopez-Maya,[31] there were four main attributes of Chavez’s energy reform. A primary goal of the reform was to centralize oil policy design and implementation within the executive branch. The goal was to reverse the 1990s market liberalization by placing PDVSA under the Ministry of Petroleum and transforming it into the sector’s ‘political leader’. This action would soon be challenged by PDVSA managers who did not want to give up the power they had acquired under La Apertura Petrolera. Second, the oil reform sought to maximize oil rent by privileging royalties on sales over taxes on profits. A persistent and worrisome drop in oil income occurred during the 1990s, due to revenue being generated through taxes rather than direct royalties. Besides, depending on international prices and volume of production, royalties involve much simpler processes, whereas taxes are subject to more complicated accounting methods. Third, the reform also aimed to bolster Venezuela’s commitments to OPEC. Fourth, and finally, the reform aimed to slow down the trend towards privatization and deregulation of PDVSA that was in motion but failed to materialize during the 1990s. The last two objectives became a source of conflict with the US government over time.

While Chávez proclaimed a move towards ‘21st Century Socialism’, his ‘rentier socialism’ mirrored the state capitalism of Carlos Pérez’s first presidency in the 1970s, a period marked by soaring oil prices. Like Pérez’s Plan of the Nation (La Gran Venezuela), Chávez’s policies re-centralized the petrostate, cancelled debts, and nationalized oil projects. The commodity boom was short-lived, and by the time oil prices began to fall in the 1980s, it left Venezuela indebted and poor.[32] Using oil revenue to pay for generous social welfare programs and nationalization of the oil industry, Perez’s first presidential term (1974-1979) was called ‘Saudi Venezuela’. In his second term (1989-1993), Perez adopted IMF austerity policies and privatization reforms; oil prices declined, and the people turned against the government in the same way they have turned against the current president, Nicolas Maduro.[33] Inaugurated to a five-year term in February 1989, Perez became the target of massive protests and street violence, which paved the way for Hugo Chávez's attempted coup and subsequent rise to power from 1998 to 2013.[34]

PDVSA began to lose autonomy as salient frictions within the government surfaced at the onset of Chavez’s arrival, which culminated in a big oil strike in December 2002. Also known as the ‘oil lockout’, the strike led to the temporary shutdown of PDVSA for two months.[35] Facing an undemocratic backlash, PDVSA overhauled the entire organization just to solidify the state control of the oil industry. Chavez replaced PDVSA’s board with political allies and merged it with the Ministry of Petroleum. After assuring that he would be directly involved in making decisions about the way PDVSA should run its business, Chavez fired nearly 18,000 workers (around 40 percent of PDVSA’s skilled employees) who participated in the strike.[36] The economic consequences of this action were dire. In the first quarter of 2003, Venezuela’s GDP diminished by 27 percent, forcing the country to import oil to satisfy domestic demand, while unemployment increased by a third, reaching 20.3 percent.[37]

The main difference in oil policy under Chavez was the degree to which PDVSA subsidized social programs for the most marginalized segments of the population. After purging the company of political opponents in 2003, PDVSA still managed to bring in large amounts of oil revenue due to high oil prices and large crude reserves. The overhauled PDVSA had greatly extended responsibilities to the state, including a mandate that PDVSA finance and manage social programs known as Misiones Boliviarianas (Bolivarian Missions). Progressive, partially effective, and ‘clientelistic’ in nature, the Misiones provided aid to the country’s lower classes through literacy training, infrastructure projects, agricultural activities, and health care. In some cases, PDVSA’s responsibilities for its social contributions were excessive. From 2008 onward, PDVSA financed two key operations through a subsidiary: a ‘price-controlled food distribution network’[38] and Fonden-Fondo de Desarrollo Nacional (National Development Fund), a politically motivated program with military participation. Founded in 2005, Fonden served as ‘off-budget military funding’ for economic development.[39]

Benefiting from the commodity boom, one can understand that the PDVSA could tolerate greater public spending on ambitious social programs. At the peak of oil prices, Venezuela made important strides in reducing inequality. From 2003 to 2008, the company spent more than $23 billion on social programs. PDVSA’s social investments improved some of the social indicators, such as tripling of spending per capita among households.[40] Over 5.25 years upon takeover, real GDP grew by 94.7% or 13.5% annually, which was considered remarkable by international standards among some observers.[41] Poverty decreased from 50 percent in 1998 to about 30 percent in 2014. The Gini index was indicative of major changes as well. In 1998, it was 0.49, but by 2012 it had declined to 0.40 (smaller numbers indicate greater equality), which the World Bank[42] regarded as one of the lowest in Latin America. Although this gave some analysts the impression that Venezuela was becoming ‘socialist’, these social programs have been criticized as being temporary and unable to address structural inequalities that are intrinsic to the Venezuelan economy.

- International Stakeholders: From ‘Hands off’ to ‘Obsolescing’ Bargaining

PDVSA’s corporate governance is rooted in the institutional framework for the energy sector and the merger of multinational companies that controlled oil production before 1976. In 1976, President Carlos Perez nationalized the oil industry, creating the state-owned PDVSA as a holding company for a group of oil and gas companies. Even though the law began expropriation by terminating oil MNE concession agreements, the oil industry was structured as it had been before nationalization—all private firms with operating licenses were fully compensated and converted into 15 state-owned companies. PDVSA was formed as a central company with 14 affiliates. For instance, Standard Oil became Lagoven, Shell became Maraven, Mobil became Llanoven, and so on.[43] PDVSA enjoyed the status of a ‘commercial entity’, independently managed and staffed with the local workforce of the former companies.[44] As a result, “corporate structures that existed before nationalization were maintained while Article 5 of the Nationalization Law left room for foreign involvement in the Venezuelan oil industry as long as it was deemed to be in the interest of the Venezuelan state”.[45]

During the 1990s, when oil prices declined, PDVSA took major steps to expand foreign operations and liberalize the oil sector as part of the government’s Apertura Petrolera. Given the extra-heavy crude in the Orinoco Oil Belt, which entailed heavy extraction and refining costs, the oil sector desperately needed joint ventures. PDVSA’s leaders, seeking to solidify management autonomy, successfully lobbied for the ‘Opening’ of the oil industry to foreign investors for the first time since 1976. As Giusti, the former CEO of PDVSA noted,[46] Apertura partially privatized PDVSA by permitting operational service agreements and strategic associations (‘equivalent to joint ventures but requiring congressional approval’), all signed with private — mostly foreign — investors, including ExxonMobil, ConocoPhillips, Shell, BP, Equinor (then Statoil), Total, Repsol YPF, China National Petroleum Corp.[47] Depending on the type of agreement, the government offered incentives to participating foreign companies that included “general corporate tax regime, reduced royalty periods, and access to international arbitration”.[48] Key Apertura deals included ExxonMobil and ConocoPhillips profit-sharing agreements in La Ceiba and the Coronoco fields, the joint venture with Veba Oel in Germany, and the acquisition of CITGO’s share in the US.[49]

Apertura’s oil deals drew criticism for potentially undermining national sovereignty. In contrast, after Chavez, PDVSA’s dealings with multinational enterprises (MNEs) demonstrated ‘obsolescing bargain’ dynamics. Increasingly becoming subservient to the state, PDVSA adopted in 2001 the controversial Hydrocarbons Organic Law (HOL). HOL established a mechanism to assign a leading role for PDVSA in all new private investments, further enabling it to lead the expropriation process. Under the law, either the state directly (through PDVSA) or mixed companies (Empresas Mixtas)—joint ventures where PDVSA had a majority participating stake—would carry out all upstream oil activities. Such activities required majority PDVSA ownership (at least 51 percent) of all future joint exploration and production ventures, as well as the payment of higher royalties by international oil companies. While HOL mandated that ‘only’ PDVSA could commercialize and export crude oil, it still allowed private corporations to carry out downstream operations, including the exportation of refined products or upgraded oil. The HOL also raised the royalty rate to 30 percent from 16.67 percent and lowered the income tax rate to 50 percent to offset the effect of the increased royalty. Although the Chavez government assured investors that HOL would not retroactively apply to existing contracts or projects, it “created a more limited role for investors than the Apertura contracts had provided. It also limited the applicability of international arbitration”.[50]

Monaldi et al[51] argue that it took nearly 5 years for Chavez to complete the expropriation process. In the case of Venezuela, commodity boom seemed crucial but various factors created strong incentives PDVSA’s nationalization, including 1) the end of the investment cycle in the oil sector; hence, the need for placement of sunken investments, 2) significant increase in the price of oil within the context of Apertura contracts that were ‘fiscally regressive’, 3) weak ‘deterrence’ of international arbitration because of the grave short-term gains against the low cost of nationalization (i.e., MNE compensation claims and legal fees under bilateral treaties), 4) delays in taking absolute control of formerly autonomous PDVSA and using it towards renationalization. Against an oil price increase from 17$ to 37$ per barrel between 1999 and 2004, the royalty rate was just 34 percent, implying that PDVSA benefited less from the global price boom than foreign MNEs.[52]

In the early 2000, PDVS reversed the market-oriented reforms that had been implemented in the 1990s. Although the 2001 HOL was consistent with the Venezuelan law that prohibited the retroactive application of laws to existing contracts, nationalization accelerated with the announcement of a new oil strategy in October 2004.[53] PDVSA had asked in January 2002 some of the foreign companies to cut output to help meet its OPEC production quota; Venezuela agreed to trim output by 6 percent, or 173,000 barrels a day, as part of OPEC’s cut of 1.5 million barrels a day.[54] In late 2004, the government declared major changes to all Apertura contracts—32 operating agreements signed during the 1990s— technically forcing investors into renegotiation of existing projects. Legislation in 2006 raised the royalty and income taxes on the four strategic associations to 33.35 percent and 50 percent, respectively.[55] It also increased the royalties on the Orinoco belt heavy oil projects from 1 percent to 16.67 percent. Then it imposed an ‘extraction’ tax in 2006, which included 1/3 of the value of all hydrocarbons produced, and a ‘windfall’ tax in 2008.[56]

By the end of 2005, major MNEs holding operating agreements signed ‘transitory agreements’ to migrate their existing contracts to PDVSA, with the noticeable exception of ExxonMobil, which had resented the royalty hikes and contractual changes earlier. Chevron, like other major foreign oil companies, agreed to pay higher royalties and taxes and gave up majority interests in their projects.[57] The 2001 HOL had already provided the background of renationalization with a minimum of 51 percent stake for PDVSA in the mixed companies. However, the government further claimed that PDVSA could take a bigger stake depending on the level of foreign investments. In October 2005, Oil Minister Rafael Ramirez pressured foreign MNEs to agree to transfer their contracts to joint ventures by the December 30th deadline, warning that if they failed to do so, they should either leave the country or face state takeover of their operations.[58]

In 2007, PDVSA concluded the partial expropriation process. This resulted in a major increase in state ownership and control over oil operations as well as a significant decline in privately owned oil production. Congress approved the remaining batch of joint venture agreements that gave CVP, a PDVSA unit, a minimum of 60% share in most of the new projects. During this takeover, PDVSA increased its ownership in four of the strategic associations from 40 percent to an average of 78 percent. Total, Statoil, Chevron, and BP agreed to give up their shares and have remained as minority partners in their Venezuelan projects. By contrast, companies like Exxon Mobil and ConocoPhillips refused to agree to PDVSA’s terms and pulled out of joint ventures. After refusing to relinquish controlling stakes, they faced full expropriation of their assets, in return for a book value reparation, considerably below market value. Exxon and Conoco, after suing PDVSA and the Chavez government, escalated their dispute by filing for arbitration in international courts.[59]

- Stagnation and the Overproduction Crisis

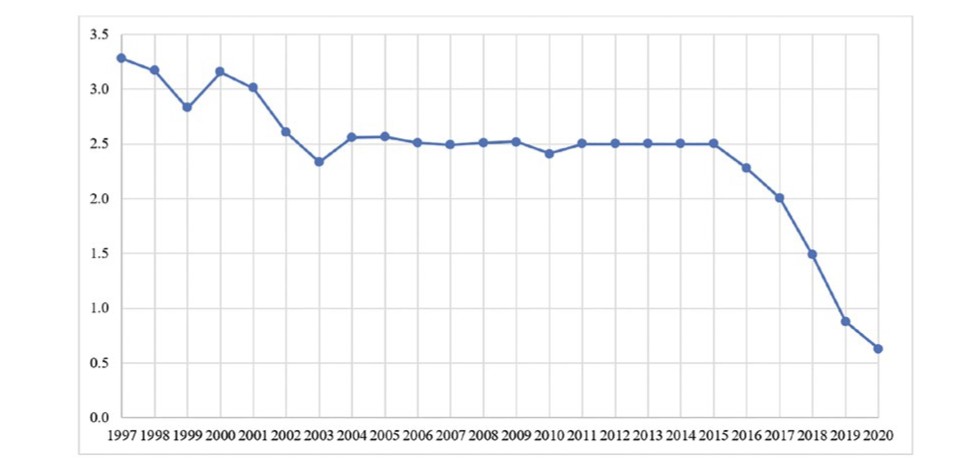

PDVSA has been facing an acute crisis since 2017. Its revenues have dropped. The reasons include shipping issues for oil, poor maintenance, fewer workers, and US sanctions on selling crude oil (2019-2022). At a time when greater FDI was needed in the oil industry, PDVSA took great risks in forcing foreign companies to pay higher taxes and produce oil in joint ventures that were majority-owned by the state. Such contractual changes not only caused uncertainty by leading to falling output from the joint ventures, but they also reduced reinvestments needed just to maintain oil production—$2.5 billion per year. In October 2005, PDVSA announced that it expected joint ventures to increase production up to 50,000 b/d under the new contract. Yet, these companies typically produced around 500,000 b/d during the oil opening in the 1990s.[60]

Source: Figure is the author’s own. Data from the U.S. Energy Information Administration (2020).

Since Maduro’s succession to the Presidency in 2013, the oil industry has descended into further economic turmoil. The oil-dependent state began to deteriorate rapidly as hyperinflation and severe food shortages set in. The World Bank issued a report calling attention to Venezuela’s current woes, which were a product of declining oil prices. In addition, it blamed the Maduro government for failing to create a ‘savings fund’ to offset what might have been an expected downturn. World Bank further noted that “during the economic boom, Venezuela did not accumulate savings to mitigate a reversal in terms of trade or to cushion the necessary macroeconomic adjustment”.[61] However, there were probably few reasons for the government to anticipate such a development since ‘peak oil’ was widely accepted as a probable outcome in world supplies. To some extent, Venezuela was a victim of a massive expansion in fracking that has made the US the world’s largest oil and gas exporter. That said, there was no doubt that the pro-Chavista government made little attempt to diversify economically. Food continued to be imported, and manufacturing made little contribution to GDP. The underdevelopment of non-energy output is, of course, a hazard for rentier states historically.

Oil prices have declined precipitously in Venezuela since the end of the commodity boom. In 2013, a barrel of Venezuelan crude oil sold for $100. A year later, the price had dropped to $88.42, and another year later it was $44.65. In early 2016, it had plummeted to $24.25. Such a steep decline would prompt most governments to rethink their development model, but the Venezuelan government has shown no signs of moving away from oil dependency so far. On the other hand, even if it did conceive of an alternative, funding for new infrastructure would be difficult to come by given the nation’s virtual bankruptcy, sharp drop in FDI, and surmounting economic problems.[62] Such problems have been so serious that by January 2017, Venezuelan oil tankers with 4 million barrels of oil and other fuels were abandoned in the Caribbean Sea. PDVSA lacked the cash to pay for safety inspections for ships carrying oil exports.[63] Figure 3 shows Venezuela’s declining annual average crude oil production from 1997 to 2020. If the global supply of oil had remained constant, Venezuela’s problems would not have been so acute. However, new technologies and offshore drilling created a spike in production that defied ‘peak oil’ expectations. By late 2015, supply mounted to 97 million barrels per diem, exceeding demand by more than a million per day. This surplus led to a severe drop in oil prices.[64]

- Transnational Oil Alliances: Russia and China in the Global Oil Market

Since 2015, PDVSA has been saddled with debt that appears unlikely to be paid from the state treasury. October-November 2017 was the acid test for the government since it was the deadline for paying bondholders $3.5 billion. This has put downward pressure on PDVSA bonds, which are a major source of revenue historically for the state.[65] Perhaps the only mitigating factor in this financial crunch was the apparent willingness of the Russian government to restructure Venezuelan debt to Russia, which stood at $3.15 billion. Signed in November 2017, the debt deal stipulated full repayment in ten years and ‘minimal’ repayments over the next six years.[66]

Rosneft, Russia’s second biggest state-controlled oil company, was one of the largest foreign creditors and a ‘financial savior’ of the Maduro regime. As early as 2013, President Putin expressed greater financial interest in Venezuela when the CEO of Rosneft, Igor Sechin, announced plans to invest $13 billion in Venezuelan oil and gas assets in the next 5 years. Russia’s involvement in PDVSA, through Rosneft and a consortium of private Russian oil companies, was aimed at: 1) promoting Russian geopolitical interests in the Caribbean region, 2) advancing economically feasible investment deals.[67] In early 2016, Rosneft announced a partnership with PDVSA in Petro Monagas, an investment of $500 million in the Orinoco Oil Belt, for offshore gas drilling.[68] Rosneft also advanced prepayments to PDVSA for crude and refined products when China, Venezuela’s other major ally, delayed its payments. In 2014, PDVSA received 6.5 million dollars in loans and advanced payments from Rosneft when the Maduro government was experiencing foreign currency shortages. In December 2016, Rosneft “also provided a $1.5 billion loan collateralized with 49.9 percent of Citgo Holdings, PDVSA’s refinery in the US”.[69]

China is PDVSA’s other major financial supporter, although, unlike Russia, it has declined to restructure Venezuela’s outstanding loans.[70] China and Russia’s relations with Venezuela are part of a global strategy to recruit allies in building a new multipolar, anti-US world order. While China seems to be more commercially driven in its foreign investments, Russia seeks both commercial and geopolitical interests in Venezuela, one which has “grown with the intent to disrupt western democracies and achieve a firm foothold in the Western Hemisphere’s largest oil reserve”.[71] China has provided Venezuela with economic and political support in exchange for future oil shipments. According to Guevara, “with roughly $67 billion invested since 2007, China has become a main source of Venezuela’s external financing, and an important partner of its oil-based economy”.[72] Indeed, in 2001, Venezuela was the first Latin American country to form a ‘strategic development partnership’ with China,[73] followed by a series of bilateral trade, infrastructure, and energy co-operation deals.

Excessive reliance on oil rent, with a sharp drop in FDI (post-2006) has deepened PDVSA’s dependence on Chinese financial support. An example of Asian foreign aid, China seeks to promote FDI through ‘bilateral lending’ and ‘opportunistic’ (‘state-to-state’)[74] alliances rather than through multilateral channels or US involvement. Such bilateral aid has been consistent with China’s ‘go-global strategy’ of promoting Chinese firms internationally since 1998. The other goals have been to meet the country’s long-term energy demands and secure access to raw materials.[75] Of particular importance is the energy deal signed in 2008 that would give a big boost to oil exports to China.[76] However, by 2012, PDVSA’s underperformance allowed export of only 640,000 barrels of oil a day to China; 200,000 of that export revenue simply went to service the country’s debts to China.[77] In the first quarter of 2018, China imported only 381,300 barrels of oil from Venezuela, hitting ‘the lowest in nearly 8 years’.[78] Other recent deals include a $5 billion credit line from China to finance investments in infrastructure, electricity, and agricultural development, including a joint-venture agreement between the PDVSA and a Chinese state-owned company, Heilongjiang Xinliang.[79]

Paradoxically, China’s ‘go-global strategy’ and bilateral diplomacy face limitations in Venezuela. The Chinese market potential has yet to be realized due to conflicts of interest in the global oil industry. In addition to limited refinery capacity, China has little proximity to Venezuela, which brings with it the high cost of transporting Venezuelan oil. The other obstacle is Venezuela’s ability to pay sovereign debt, which undermines China’s continued investments in the Orinoco Oil Belt. PDVSA only signed short-term sales contracts because of China’s interest in cheap fuel oil, whereas PDVSA seeks to increase the price of its heavy oil products. Finally, China has “signaled its willingness to work with opposition leaders” (Juan Guaido) for debt repayment, which indicates China’s declining confidence in the Maduro government.[80] Until China’s potential is fully realized, Central and North America remain the most important markets for PDVSA’s crude oil export.

- CITGO: The US Overreach and Sanctions Dilemma

Welcomed at one time for its charitable donations of fuel oil in the USA, CITGO has become a major player in the ongoing crisis with the US government. In the last decade or so, Venezuela’s relationships with the US are the opposite of those with Russia and China, which are generally aligned with states considered America’s adversaries. PDVSA bought CITGO in 1990, a Houston-based oil company that has been in business since 1910 and exports close to a million barrels of oil to the US annually. CITGO—fully owned PDVSA’s subsidiary—accounts for the largest share of Venezuela’s foreign downstream (refinery) operations in the US, along with operations in the Caribbean and Europe.[81] At its peak in 2007, Venezuela exported an average of 1.1 million b/d of crude oil to the US.

In the first round of sanctions that began in August 2017, the US issued “an executive order that limited access to debt capital and prevented PDVSA from receiving cash distributions from CITGO”.[82] In January 2019, the White House imposed broader sectoral sanctions on PDVSA’s crude oil shipments to the US. The sanctions were aimed at unseating President Nicolas Maduro, whose last election in 2018 the US viewed as illegitimate. Pursuant to President Trump’s Executive Order, the US Treasury banned access to US financial markets and oil supplies for all PDVSA joint ventures and its subsidiaries, including a blockage on PDVSA’s property under US jurisdiction and a ban on all US companies and individuals from ‘engaging in transactions’ with PDVSA[83]. As a result, all U.S. imports of Venezuela’s crude oil were discontinued in March 2019.[84] In April 2019, the US Treasury’s Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) took steps to exempt certain transactions from US sanctions under amended licenses that would allow “only transactions necessary for the maintenance of ‘essential operations’ through June 1, 2022”.[85]

Even after securing special permissions, the ban on export authorizations for PDVSA’s foreign partners negatively impacted US oil interests in Venezuela. Such an embargo left oil companies like Chevron, Eni, Repsol “with billions of dollars in unpaid dividends and debts that had been settled through Venezuelan oil cargos”.[86] While hoping to unseat the Maduro government through economic sanctions, the White House left CITGO out of the equation from the beginning since it was a strategically important part of the American business. CITGO is the operator of three of the largest oil refineries that provide 750,000 barrels per day (b/d), including one in Chicago that is a regional energy hub. For instance, in 2015, CITGO provided 15 billion gallons of gasoline to American drivers.[87]

Given the strategic importance of CITGO to American oil interests, the US expects to carry on buying oil from PDVSA with little disruption. This depends on the continued viability of CITGO- PDVSA’s most valued asset abroad. However, CITGO had already become liable for Venezuela’s debt when foreign companies attempted to seize PDVSA’s CITGO shares as compensation for expropriated assets in 2006-2007. Therefore, the US Treasury (OFAC) took further steps in October 2019 to safeguard CITGO “from seizure in legal challenges against Venezuela to preserve the asset for the interim government if it takes power”.[88] This indicated that bondholders would be unable to recover their collateral, which consists of shares in CITGO, until January 22, 2020, even in the event of a default on those bonds. In May 2020, CITGO’s new board, appointed by the interim (US-backed) government of Juan Guaido, reached an agreement with bondholders to prevent creditors from liquidating CITGO’s assets until May 2020. OFAC extended the protection for CITGO through October 20, 2020.[89]

Furthermore, obstacles remain to the full lifting of US sanctions. Given the oil shortage caused by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, President Biden initiated talks with Venezuelan officials about easing some of the sanctions before the expiry date (June 1, 2022). Around March 2022, traders were speculating that such a move might lead to the relaxation of restrictions on Venezuelan bond purchases as well. However, since the Biden administration does not officially acknowledge Maduro as the leader of Venezuela, US investors are still prohibited from buying the country’s debt, unlike European investors who are aggressively buying the bonds.[90]

Ironically, US sanctions against PDVSA resulted in increased isolation and consolidation of power for the Maduro regime. The desired effect, namely the strengthening of the Guaido-led provisional government and a democratic transition, failed to materialize. Furthermore, the provisional government was unable to maintain control over CITGO’s management. This makes CITGO’s future uncertain, as the board of directors keeps changing and PDVSA tries to regain control of the company under any future settlement with the US.

- Policy Implications of the Research for Oil Industry Managers

This paper has examined PDVSA’s strategic importance for North America and its dependence on the US as a ‘lender of last resort’ and leading global trader. When PDVSA defaulted on sovereign bonds, the US kept CITGO secure by renewing exemptions from US sanctions. This prevented creditors from liquidating PDVSA’s CITGO shares—‘American cash cow’ and the most valued asset PDVSA holds abroad.[91] Big US oil companies like Chevron benefited from the exemption and further easing of US sanctions in 2022, which would help resume their operations in Venezuela. While Chevron remains committed to investing in Venezuela, CITGO appears to benefit significantly from reopening trade with PDVSA.[92] This goes contrary to the emergence of a multi-polar world order (China, Russia) that would undermine US oil interests in Venezuela.

US oil industry managers are capitalizing on the increasing tensions between PDVSA and its trading partners, which are occurring against the backdrop of Western sanctions on Russian oil. Although PDVSA has repeatedly expressed interest in increasing oil trade with China to diversify oil exports from the US, it must come up with a feasible strategy. Chinese and Russian investments are high risk and have far bigger liabilities than originally thought, as they are no longer reliable markets for Venezuelan oil. Even when oil prices were high, there were structural fault lines in PDVSA that would open further after prices dropped. Rosneft’s exit from Venezuela in March 2020 amid US sanctions was a loss of financial and technical capacity for PDVSA.[93] On the other hand, given PDVSA’s drop in oil production and the drop in oil prices after the commodity boom, China finds it harder to trust Venezuela with its outstanding loans (around $20 billion)[94] and may be even reluctant to make more oil investments. China seems to be “focused more on getting its payments back than strengthening its diplomatic relations”.[95] Until China’s potential is fully realized as a trading partner, North America remains the dominant market for PDVSA’s crude oil export.

As for the recommendations and directions for future research, it is conceivable that as oil prices keep rising, PDVSA may once again achieve a modicum of normalcy. This is an area of research that needs to be further investigated. In June 2022, the US State Department gave the green light to two European companies, Italy’s Eni and Spain’s Repsol, to resume shipments of Venezuelan oil to Europe. This could potentially benefit US oil companies by helping to reduce Europe’s dependence on Russia and redirecting some of PDVSA’s shipments from China.[96] With recovering oil prices lately, “Venezuelan oil production recovered from a historically low level of 500,000 barrels per day (b/d) in 2020 to a yearly average of 636,000 b/d in 2021 and, most recently, 788,000 b/d in February 2022”.[97] However, this still begs the question of how PDVSA can stave off another crisis that seems almost inevitable for rentier states based on oil.

Conclusion

Combining institutional theory of the firm with resource dependency analysis, this paper examined the evolving corporate strategy of Venezuela’s state-owned oil company, PDVSA. It has examined the multitude of stakeholders involved in oil policy making, including local institutional actors and transnational oil interests. Certainly, obstacles remain to PDVSA’s performance and potential for investment arising from rentier economy distortions, especially since the rise of President Chavez in 1998 and subsequently. As of August 2020, Venezuela produced 360,000 barrels a day (b/d) of crude oil (excluding condensates)—the lowest amount ever recorded since 1973. Several factors continue to drive down crude oil production, such as a lack of investments, maintenance problems in oil infrastructure, a shortage of heavy oil diluents, and loss of human capital. US sanctions in 2019 and 2020 decreased foreign investment and limited markets for Venezuelan oil.[98]

Since the easing of US sanctions in 2022, US oil industry managers need much stronger incentives to resume business talks with PDVSA. Because of the changing political climate and increased tariffs on Venezuelan oil under President Trump, however, these talks might be significantly delayed. To boost oil output, the Venezuelan government signed new oil deals in late 2018 with seven companies, akin to private investments (‘operating agreements’) nationalized by Chavez. Although the plan seemed like a gesture to allow more foreign participation, it faced several hurdles before the closing of the deal. Most of the companies involved were small and little known, with no recognized experience operating oil fields, and US sanctions have prevented experienced firms from working with PDVSA.[99]

With the resumption of diplomatic talks in 2022, the US can utilize other incentives, such as promoting private sector investments. Such investments should target stronger technical expertise, managerial, and organizational resources. In CITGO’s case, for instance, “the United States could encourage the company to make targeted investments to update pipeline infrastructure in Venezuela”.[100] Another significant challenge lies in creating compelling incentives for former PDVSA employees to return to work in Venezuela. Consequently, should a regime change occur, the central question becomes which oil companies will work with PDVSA, rather than focusing solely on FDI. However, domestic institutions and U.S. oil policy in Latin America could significantly affect the outcomes of these incentives.

Overall, this paper has argued that PDVSA’s oil strategy can’t overcome the paradox of “rentier socialism”, geared towards using oil income as a windfall for development. In the long run, PDVSA’s resource dependence and its alliance-based trading will only temporarily mask the underlying over-production crisis. Moreover, the US will struggle to control Venezuelan oil, a situation compounded by Donald Trump's executive order set to begin in early April 2025. This order mandated a 25% tariff on U.S. trades for any nation buying oil or gas from Venezuela.[101] In addition to higher oil prices in the US and reduced imports of Venezuelan oil, China (as the largest buyer of Venezuelan oil) will face greater costs, potentially reducing its imports of Venezuelan crude. With a loss of export income, the state-owned PDVSA is structurally limited in its ability to diversify resources and operate effectively in the global market.

Bibliography:

- Acemoglu, D., Robinson, J. (2012). Why Nations Fail: The Origins of Power, Prosperity, and Poverty, ed. New York: Crown;

- Aizhu, C., Tan, F. (2018, June 15). Venezuela oil exports to China slump, may hit lowest in nearly 8 years: sources, data. Reuters;

- Associated Press. (2002, January 10). Venezuela asks foreign oil companies to trim output;

- Beblawi, H. (1987). The Rentier State in the Arab World. Arab Studies Quarterly, 9(4). Available at: <http://www.jstor.org/stable/41857943>;

- Berg, R. (2021, October 12). The Role of the Oil Sector in Venezuela’s Environmental Degradation and Economic Rebuilding. Available at: <https://www.csis.org/analysis/role-oil-sector-venezuelas-environmental-degradation-and-economic-rebuilding>;

- BP Statistical Review of World Energy. (2020). Statistical Review of World Energy 2020. 69th Available at: <https://www.bp.com/content/dam/bp/business-sites/en/global/corporate/pdfs/energy-economics/statistical-review/bp-stats-review-2020-full-report.pdf>;

- Bull, W. (2008, September 25). Venezuela signs Chinese oil deal, BBC News;

- Cardin, P. (1993). Rentierism and the Rentier State: A Comparative Examination. McGill University, PhD thesis;

- (2019). Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela: General Trends, in Economic Survey of Latin America and the Caribbean. Available at: <https://repositorio.cepal.org/bitstream/handle/11362/44675/144/EEI2019_Venezuela_en.pdf>;

- (2021, April 28). Venezuela: Background and U.S. Relations. Available at: <https://sgp.fas.org/crs/row/R44841.pdf>;

- (2022, May 23). Venezuela: Overview of U.S. Sanctions. Available at: <https://sgp.fas.org/crs/row/IF10715.pdf>;

- Cuervo-Cazurro, A., Inkpen, A., Musacchio, A., Ramaswamy, K. (2014). Government as Owners: State-owned multinational companies. 923, Journal of International Business Studies, Vol. 45, August;

- Cunningham, N. (2017, August 8). Venezuela’s deteriorating crisis could send oil to $80 a barrel. Business Insider;

- Dachevsky, F., Kornblihtt J. (2017). The Reproduction and Crisis of Capitalism in Venezuela under Chavismo. Latin American Perspectives, 44(1): 78-93;

- De La Cruz, A. (2020, April 10). Rosneft’s Withdrawal amid U.S. Sanctions Contributes to Venezuela’s Isolation. Available at: <https://www.csis.org/analysis/rosnefts-withdrawal-amid-us-sanctions-contributes-venezuelas-isolation>;

- Di John, J. (2010). From Windfall to Curse? Oil and Industrialization in Venezuela, 1920 to the Present. Pennsylvania University Press;

- El-Katiri, L. (2014). The Guardian State and its Economic Development Model. Journal of Development Studies, 50:1;

- Evans, P. (1995). Embedded Autonomy: States and Industrial Transformation. Princeton University Press: New Jersey, USA;

- Gallas, D. (2017, November 15). Russia and Venezuela agree debt deal. BBC News;

- Garcia, I. (2021, December 22). The Future of the Sino-Venezuelan Relationship: Make or Break? Harvard International Review;

- Garip, P. (2021, August 12). Venezuela Negotiating Agenda in Crosscurrent. Argus Media;

- Giusti, L. E. (1999). La Apertura: The Opening of Venezuela’s Oil Industry. Journal of International Affairs, Fall, Vol. 53, No. 1;

- Gokay, B. (2017, April 10). Venezuela crisis is the hidden consequence of Saudi Arabia’s oil price war. Available at: <https://theconversation.com/venezuela-crisis-is-the-hidden-consequence-of-saudi-arabias-oil-price-war-82178>;

- Gramer, R. (2017, January 26). Venezuela is so Broke it can’t even Export Oil. Foreign Policy;

- Guevara, C. (2020, January 13). China’s support for the Maduro regime: Enduring or fleeting? Atlantic Council;

- Hermoso, J., Fermin. V. (2019, January 14). Venezuela-China explained: The Belt and Road. SupChina;

- Hertog, S. (2010). Defying the Resource Curse: Explaining Successful State-Owned Enterprises in Rentier States. 261, World Politics, Vol. 62, No. 2, April;

- Hults, D. R. (2011). Petróleos de Venezuela, S.A. (PDVSA): from independence to subservience. 436, in D. G. Victor, D. R. Hults, & Thurber M. C. (eds), Oil and Governance: State-Owned Enterprises and the World Energy Supply. Cambridge University Press;

- International Business Times (2022, March 31). Exclusive-Venezuela’s PDVSA Seeks Oil Tankers in Anticipation of US Sanctions Easing;

- Jaffe, A. M. (2018, January 23). How Much Worse Can It Get for Venezuela’s State Oil Firm PDVSA? Council on Foreign Relations. Available at: <https://www.cfr.org/blog/how-much-worse-can-it-get-venezuelas-state-oil-firm-pdvsa>;

- Jaffe, A. M. (2019, February 21). Amid Political Uncertainties, Venezuela’s Oil Industry Situation Worsens. Council on Foreign Relations. Available at: <https://www.cfr.org/blog/amid-political-uncertainties-venezuelas-oil-industry-situation-worsens>;

- Jones, B. (2007). Hugo! The Hugo Chavez Story from Mud Hut to Perpetual Revolution. Steerforth Press, Hanover: New Hampshire Jones;

- Kaplan, S. B., Penfold, M. (2019). China-Venezuela Economic Relations: Hedging Venezuelan Bets with Chinese Characteristics. 6, Wilson Center, Washington D.C: United States;

- Karl, T. L. (1997). The Paradox of Plenty: Oil Booms and Petro-States. Berkeley: University of California Press;

- Kerr, J. (2006, January 3). Venezuela Enters New Year with New Oil Contracts. IHS Global Insight;

- Koivumaeki, R. I. (2015). Evading the Constraints of Globalization: Oil and Gas Nationalization in Venezuela and Bolivia. Comparative Politics, 113, Vol.48, No.1, October;

- Kott, A. (2012). Assessing Whether Oil Dependency in Venezuela Contributes to National Instability. Journal of Strategic Security, Vol. 5, No. 3, Fall;

- Krauss, C. (2018, October 1). Venezuela’s Crisis Imperils Citgo, Its American ‘Cash Cow’. New York Times;

- Labrador, R. C. (2019, February 5). Maduro’s Allies: Who Backs the Venezuelan Regime? Council on Foreign Relations. Available at: <https://www.cfr.org/in-brief/maduros-allies-who-backs-venezuelan-regime>;

- Lander, E. (2016). The implosion of Venezuela’s rentier state. Transnational Institute New Politics Papers. Available at: <https://www.tni.org/en/publication/the-implosion-of-venezuelas-rentier-state>;

- Lander, L., Lopez-Maya, M. (2002). Venezuela’s Oil Reform and Chavismo. NACLA Report on the Americas, 36 (1): 21–23;

- Lander, L. E. (2007). Venezuela’s balancing act: Big oil, OPEC and national development. NACLA Report on the Americas, 25, Vol. 34, Issue. 4, (Jan/Feb): 25-30;

- Lopez-Maya, M. (2014). The Political Crisis of Post-Chavismo. Social Justice, Vol. 40, No. 4 (134);

- Losman, D. L. (2010). The Rentier State and National Oil Companies: An Economic and Political Perspective. Middle East Journal, Vol. 64, No. 3, Summer;

- P. J., Weinthal, E. (2006). Rethinking the Resource Curse: Ownership Structure, Institutional Capacity, and Domestic Constraints. Annual Review of Political Science, Vol. 9;

- Mahdavy, H. (1970). The Pattern and Problems of Economic Development in Rentier States: The Case of Iran, in Cook, M. A. (eds), Studies in the Economic History of the Middle East. Oxford University Press: Oxford, London;

- Malleson, T. (2010). Cooperatives and the ‘Bolivarian Revolution’ in Venezuela. Affinities: A Journal of Radical Theory, Culture, and Action, 157, Volume 4, Number 1, Summer;

- Manzano, O., Monaldi, F. (2010). The Political Economy of Oil Contract Renegotiation in Venezuela., in H. William, F. Sturzenegger (eds.) The Natural Resources Trap: Private Investment without Public Commitment. MIT Press: MA, Cambridge;

- Mares, D. R., Altamarino, N. (2007). Venezeula’s PDVSA and World Energy Markets: Corporate Strategies and Political Factors Determining Its Behavior and Influence. The James Baker III Institute for Public Policy, Rice University, March;

- Mommer, B. (1990). Oil Rent and Rent Capitalism: The Example of Venezuela, Review. Fernand Braudel Center, Vol.13, No.4, Fall;

- Monaldi, F., Hernandez, I., La Rosa, J. (2020). The Collapse of the Venezuelan Oil Industry: The Role of Above-Ground Risks Limiting FDI, Working Paper. 11, Center for Energy Studies, Rice University’s Baker Institute for Public Policy;

- Negroponte, D. V. (2018, June 19). Russian Interests in Venezuela: A New Cold War? American Quarterly;

- Noreng, O. (1994). National Oil Companies and Their Government Owners: The Politics of Interaction and Control. The Journal of Energy and Development, 198, Spring, Vol. 19, No. 2;

- Palacios, L., Monaldi F. (2022, March 23). Venezuela Oil Sanctions: Not an Easy Fix. Available at: <https://www.energypolicy.columbia.edu/research/commentary/venezuela-oil-sanctions-not-easy-fix#_edn6>;

- Parraga, M., Spetalnick, M. (2022, June 6). U.S. to let Eni, Repsol ship Venezuela oil to Europe for debt. Reuters;

- Parraga, M. (2013, September 4). Venezuela lacked good faith ConocoPhillips Seizure-World Bank. Reuters;

- Parraga, M. (2021, October 28). Exclusive-U.S. Oil Refiner Citgo Petroleum Readies New Board Shakeup. Reuters;

- Parraga, M. (2025, March 25). Oil loading slows at Venezuela’s ports amid US tariffs, license termination, data shows. Reuters.

- Plummer, R. (2013, March 5). Hugo Chavez leaves Venezuela in economic muddle. BBC News;

- Pons, C. (2018, September 10). Exclusive: Venezuela signs oil deals similar to ones rolled back under Chavez – document. Reuters;

- Ravell, A. F. (2011). A brief overview of Venezuela’s Oil Policies. Available at: <https://www.lexology.com/library/detail.aspx?g=01cf61f2-9591-4ac3-9ceb-59ac37090e13>;

- Rosales, A. (2016). Deepening Extractivism and Rentierism: China’s Role in Venezuela’s Bolivarian Developmental Model. 560, Canadian Journal of Development Studies, 37, Issue. 4, 560-7, December;

- Rosales, A. (2018). Pursuing foreign investment for nationalist goals: Venezuela’s hybrid resource nationalism. Business and Politics, 443, Vol. 20, Issue 3;

- Ross, M. (2015). What Have We Learned about the Resource Curse? Annual Review of Political Science. 18: 239–259.

- Sachs, J. D., Warner, A. (1999). The Big Rush, Natural Resource Booms and Growth. Journal of Development Economics, 59 (1, Jun).

- Sachs, J. D., Warner, A. (1995). Natural Resource Abundance and Economic Growth. NBER Working Paper No. 5398. Available at: <https://www.nber.org/papers/w5398>.

- SEC Filing. (2016). PDVSA: Petróleos de Venezuela, S.A. SEC, 128, Edgar Archives. Available at: <https://www.sec.gov/Archives/edgar/data/906424/000119312516712239/d171369dex99t3e.htm>;

- Sigalos, M. (2019, February 7). China and Russia loaned billions to Venezuela — and then the presidency went up for grabs. CNBC;

- Singh, J.M., Chen, G. C. (2018). State-owned enterprises and the political economy of state–state relations in the developing world. Third World Quarterly, 39:6, 1077-1097.

- Smith, B., Waldner, D. (2021). Rethinking the Resource Curse. Cambridge University Press: London, UK.

- Smith, M. (2013, January 11). Venezuela, Oil and Chavez: A Tangled Tale. Available at: <www.com>;

- Stein, P. (2009, November 16). Venezuela: The Background. APS Review of Oil Market Trends, Vol. 73, Issue 20;

- Styhre, A. (2019). The institutional theory of the firm: Embedded Autonomy. Routledge: London, UK;

- Strønen, I. Å. (2020). Venezuela’s oil specter: Contextualizing and historicizing the Bolivarian attempt to sow the oil. History and Anthropology, 33(4), pp. 472–495. Available at: <https://doi.org/10.1080/02757206.2020.1762588>;

- Suggett, J. (2010, August 4). Latest Venezuela-China Deals: Orinoco Agriculture, Civil Aviation, Steel, and $5 Billion Credit Line. Available at: <www.com>;

- Sullivan, M. P. (2009, July 28). Venezuela: Political Conditions and U.S. Policy. Congressional Research Service (CRS), 3-4, RL32488, Washington, DC;

- The Independent. (2010, December 29). Carlos Andres Perez: President of Venezuela during the oil boom who was later forced out of office;

- Tian, N., Lopes da Silva, D. (2019, April 2). The crucial role of the military in the Venezuelan crisis. Available at: <https://www.sipri.org/commentary/topical-backgrounder/2019/crucial-role-military-venezuelan-crisis>;

- UN Comtrade, The Observatory of Economic Complexity. (2021, May 12). Venezuela: petroleum industry as share of exports 2010-2019.Statista - The Statistics Portal;

- US Energy Information Administration. (2019, January 7). Background Reference: Venezuela. Available at: <https://www.eia.gov/international/content/analysis/countries_long/Venezuela/background.htm>;

- US Energy Information Administration. (2020, November 30). Venezuela: Executive Summary-Analysis. Available at: <https://www.eia.gov/international/analysis/country/VEN>.

- Venables, A. (2016). Using Natural Resources for Development: Why Has It Proven So Difficult? Journal of Economic Perspectives.30 (1): 161–184;

- Vizcaino, M. E., Yapur, N. (2022, March 8). Defaulted Venezuela Bonds Are Luring Buyers Betting on US Deal. Bloomberg;

- Wilson, J. (2015). Understanding resource nationalism: economic dynamics and political institutions. Contemporary Politics, 2015, Vol. 21, No. 4, 399-416. 400-401;

- Wiseman, C., Beland, D. (2010). The Politics of Institutional Change in Venezuela: Oil Policy During the Presidency of Hugo Chávez. Canadian Journal of Latin American and Caribbean Studies, Vol. 35, No. 70 (2010);

- World Bank. (2017). The World Bank in Venezuela. Available at: <http://www.worldbank.org/en/country/venezuela/overview>;

- World Bank. (2022, May 22). Oil Rents as % of GDP. The World Bank Data Catalog. Available at: <https://datacatalog.worldbank.org/country/benin?page=29>;

- Yates, D. A. (1996). The Rentier State in Africa: Oil Rent Dependency and Neo-Colonialism In the Republic of Gabon. Africa World Press. Trenton: NJ.

Footnotes

[1] CEPAL. (2019). Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela: General Trends, in Economic Survey of Latin America and the Caribbean. Available at: <https://repositorio.cepal.org/bitstream/handle/11362/44675/144/EEI2019_Venezuela_en.pdf>.

[2] Strønen, I. Å. (2020). Venezuela’s oil specter: Contextualizing and historicizing the Bolivarian attempt to sow the oil. History and Anthropology, 33(4), pp. 472–495. Available at: <https://doi.org/10.1080/02757206.2020.1762588>.

[3] US Energy Information Administration. (2019, January 7). Background Reference: Venezuela. Available at: <https://www.eia.gov/international/content/analysis/countries_long/Venezuela/background.htm>.

[4] Wilson, J. (2015). Understanding resource nationalism: economic dynamics and political institutions. Contemporary Politics, 2015, Vol. 21, No. 4, pp. 399–416, 400-401.

[5] Mommer, B. (1990). Oil Rent and Rent Capitalism: The Example of Venezuela, Review. Fernand Braudel Center, Vol. 13, No. 4, Fall, pp. 417-437; Cardin, P. (1993). Rentierism and the Rentier State: A Comparative Examination. McGill University, PhD thesis; Karl, T. L. (1997). The Paradox of Plenty: Oil Booms and Petro-States. Berkeley: University of California Press; Acemoglu, D., Robinson, J. (2012). Why Nations Fail: The Origins of Power, Prosperity, and Poverty, ed. New York: Crown; Losman, D. L. (2010). The Rentier State and National Oil Companies: An Economic and Political Perspective. Middle East Journal, Vol. 64, No. 3, Summer, pp. 427-445; Lopez-Maya, M. (2014). The Political Crisis of Post-Chavismo. Social Justice, Vol. 40, No. 4 (134), pp. 68-87; Wilson, J., 399–416; Lander, E. (2016). The implosion of Venezuela’s rentier state. Transnational Institute New Politics Papers. Available at: <https://www.tni.org/en/publication/the-implosion-of-venezuelas-rentier-state>.

[6] Karl, T. L. (1997).

[7] Di John, J. (2010). From Windfall to Curse? Oil and Industrialization in Venezuela, 1920 to the Present. Pennsylvania University Press. A rentier state or economic model tends to emerge when “mineral and fuel production is at least 10 percent of GDP and mineral, and fuel exports are at least 40 percent of total exports” (Di John. (2010). p. 79).

[8] Sachs, J. D., Warner, A. (1999). The Big Rush, Natural Resource Booms and Growth. Journal of Development Economics, v. 59 (1, Jun), pp. 43-76; Venables, A. (2016). Using Natural Resources for Development: Why Has It Proven So Difficult? Journal of Economic Perspectives. 30(1): 161–184; Ross, M. (2015). What Have We Learned about the Resource Curse? Annual Review of Political Science. 18: 239–259; Sachs, J. D., Warner, A. (1995). Natural Resource Abundance and Economic Growth. NBER Working Paper No. 5398. Available at: <https://www.nber.org/papers/w5398>.

[9] Manzano, O., Monaldi, F. (2010). The Political Economy of Oil Contract Renegotiation in Venezuela., in H. William, F. Sturzenegger (eds.), The Natural Resources Trap: Private Investment without Public Commitment; MIT Press: MA, Cambridge.

[10] Wiseman, C., Beland, D. (2010). The Politics of Institutional Change in Venezuela: Oil Policy During the Presidency of Hugo Chávez. Canadian Journal of Latin American and Caribbean Studies, Vol. 35, No. 70 (2010), pp. 141-164.; Styhre, A. (2019). The institutional theory of the firm: Embedded Autonomy, Routledge: London, UK.

[11] Dachevsky, F., Kornblihtt J. (2017). The Reproduction and Crisis of Capitalism in Venezuela under Chavismo. Latin American Perspectives, 44(1): 78-93, p. 78.

[12] Luong. P. J., Weinthal, E. (2006). Rethinking the Resource Curse: Ownership Structure, Institutional Capacity, and Domestic Constraints. Annual Review of Political Science, Vol. 9, pp. 241-263.

[13] Karl, T. L. (1997).

[14] Mahdavy, H. (1970). The Pattern and Problems of Economic Development in Rentier States: The Case of Iran, in Cook, M. A. (eds). Studies in the Economic History of the Middle East, Oxford University Press: Oxford, London, pp. 427-476.

[15] Sachs, J. D., Warner, A., (1999), pp. 43-76.; Smith, M. (2013, January 11). Venezuela, Oil and Chavez: A Tangled Tale. Available at: <www.oilprice.com>; Smith, B., Waldner, D. (2021). Rethinking the Resource Curse. Cambridge University Press: London, UK.

[16] Beblawi, H. (1987). The Rentier State in the Arab World. Arab Studies Quarterly, 9(4), pp. 383–398. Available at: <http://www.jstor.org/stable/41857943>; Yates, D. A. (1996). The Rentier State in Africa: Oil Rent Dependency and Neo-Colonialism In the Republic of Gabon. Africa World Press. Trenton: NJ.; Losman, D. L., pp. 427-445; Wilson, J., pp. 400-401.

[17] El-Katiri, L. (2014). The Guardian State and its Economic Development Model. Journal of Development Studies, 50:1, pp. 22-34; Wilson, J. (2015). p. 405.

[18] Di John, J. (2010). p. 79.

[19] Hults, D. R. (2011). Petróleos de Venezuela, S.A. (PDVSA): from independence to subservience. 436, in D. G. Victor, D. R. Hults, & Thurber M. C. (eds). Oil and Governance: State-Owned Enterprises and the World Energy Supply. Cambridge University Press, pp. 418-477.

[20] Hults, D. R. (2011). p. 437.

[21] Noreng, O. (1994). National Oil Companies and Their Government Owners: The Politics of Interaction and Control. The Journal of Energy and Development, 198, Spring, Vol. 19, No. 2, pp. 197-226.

[22] Di John, J. (2010). pp. 83-86.

[23] Singh, J. M., Chen, G. C. (2018). State-owned enterprises and the political economy of state–state relations in the developing world. 1077, Third World Quarterly, 39:6, pp. 1077-1097.

[24] Evans, P. (1995). Embedded Autonomy: States and Industrial Transformation. Princeton University Press: New Jersey, USA.

[25] Styhre, A. (2019). p. 1.

[26] Cuervo-Cazurro, A., Inkpen, A., Musacchio, A., Ramaswamy, K. (2014). Government as Owners: State-owned multinational companies. 923, Journal of International Business Studies, Vol. 45, August, pp. 919-942.

[27] Mares, D. R., Altamarino, N. (2007). Venezeula’s PDVSA and World Energy Markets: Corporate Strategies and Political Factors Determining Its Behavior and Influence. The James Baker III Institute for Public Policy, Rice University, March, p. 15; Hertog, S. (2010). Defying the Resource Curse: Explaining Successful State-Owned Enterprises in Rentier States. 261, World Politics, Vol. 62, No. 2, April, pp. 261-301; Lander, E. (2016). The implosion of Venezuela’s rentier state. Transnational Institute New Politics Papers. Available at: <https://www.tni.org/en/publication/the-implosion-of-venezuelas-rentier-state>.

[28] Rosales, A. (2016). Deepening Extractivism and Rentierism: China’s Role in Venezuela’s Bolivarian Developmental Model. 560, Canadian Journal of Development Studies, Vol. 37, Issue 4, 560-7, December.

[29] SEC Filing. (2016). PDVSA: Petróleos de Venezuela, S.A. SEC, 128, Edgar Archives. Available at: <https://www.sec.gov/Archives/edgar/data/906424/000119312516712239/d171369dex99t3e.htm>.

[30] CRS. (2021, April 28). Venezuela: Background and U.S. Relations, p. 2. Available at: <https://sgp.fas.org/crs/row/R44841.pdf>.

[31] Lander, L., Lopez-Maya, M. (2002). Venezuela’s Oil Reform and Chavismo. NACLA Report on the Americas, 36 (1): 21–23.

[32] Lopez-Maya, M. (2014). p. 74.

[33] The Independent. (2010, December 29). Carlos Andres Perez: President of Venezuela during the oil boom who was later forced out of office.

[34] Sullivan, M. P. (2009, July 28). Venezuela: Political Conditions and U.S. Policy. Congressional Research Service (CRS), 3-4, RL32488, Washington, DC.

[35] Smith, M. (2013, January 11). Venezuela, Oil and Chavez: A Tangled Tale. Available at: <www.oilprice.com>.

[36] Kott, A. (2012). Assessing Whether Oil Dependency in Venezuela Contributes to National Instability. Journal of Strategic Security, Vol. 5, No. 3, Fall, pp. 69-86.

[37] Jones, B. (2007). Hugo! The Hugo Chavez Story from Mud Hut to Perpetual Revolution. Steerforth Press, Hanover: New Hampshire Jones, p. 43.

[38] Hults, D. R. (2011). p. 434.

[39] Tian, N., Lopes da Silva, D. (2019, April 2). The crucial role of the military in the Venezuelan crisis. Available at: <https://www.sipri.org/commentary/topical-backgrounder/2019/crucial-role-military-venezuelan-crisis>.

[40] Kott, A. (2012). p. 79.

[41] Malleson, T. (2010). Cooperatives and the ‘Bolivarian Revolution’ in Venezuela. Affinities: A Journal of Radical Theory, Culture, and Action, 157, Vol. 4, Number 1, Summer, pp. 155-175.

[42] World Bank. (2017). The World Bank in Venezuela. Available at: <http://www.worldbank.org/en/country/venezuela/overview>.

[43] Lander, L. E. (2007). Venezuela’s balancing act: Big oil, OPEC and national development. NACLA Report on the Americas, 25, Vol. 34, Issue 4, (Jan/Feb): 25-30.

[44] Giusti, L. E. (1999). La Apertura: The Opening of Venezuela’s Oil Industry. Journal of International Affairs, Fall, Vol. 53, No. 1, pp. 117-128; Ravell, A. F. (2011). A brief overview of Venezuela’s Oil Policies. Available at: <https://www.lexology.com/library/detail.aspx?g=01cf61f2-9591-4ac3-9ceb-59ac37090e13>.

[45] Wiseman, C., Beland, D. (2010). p. 144.

[46] Giusti, L. E. (1999) p. 188.

[47] Jaffe, A. M. (2019, February 21). Amid Political Uncertainties, Venezuela’s Oil Industry Situation Worsens, Council on Foreign Relations. Available at: <https://www.cfr.org/blog/amid-political-uncertainties-venezuelas-oil-industry-situation-worsens>.

[48] Ravell, A. F. (2011).

[49] CRS. (2021). p. 10.

[50] Monaldi, F., Hernandez, I., La Rosa, J. (2020). The Collapse of the Venezuelan Oil Industry: The Role of Above-Ground Risks Limiting FDI, Working Paper. 11, Center for Energy Studies, Rice University’s Baker Institute for Public Policy.

[51] Monaldi, F., Hernandez, I., La Rosa, J. (2020). p. 13.

[52] Koivumaeki, R. I. (2015). Evading the Constraints of Globalization: Oil and Gas Nationalization in Venezuela and Bolivia. Comparative Politics, 113, Vol. 48, No. 1, October, pp. 107-125.

[53] Koivumaeki, R. I. (2015). p. 113.

[54] Associated Press. (2002, January 10). Venezuela asks foreign oil companies to trim output.

[55] Stein, P. (2009, November 16). Venezuela: The Background. APS Review of Oil Market Trends, Vol. 73, Issue 20.

[56] Monaldi, F., Hernandez, I., La Rosa, J. (2020). p. 12.

[57] Parraga, M. (2013, September 4). Venezuela lacked good faith ConocoPhillips Seizure-World Bank. Reuters.

[58] Kerr, J. (2006, January 3). Venezuela Enters New Year with New Oil Contracts. IHS Global Insight.

[59] Stein, P. (2009, November 16); Monaldi, F., Hernandez, I., La Rosa, J. (2020). p. 12.

[60] Kerr, J. (2006, January 3).

[61] World Bank. (2017). The World Bank in Venezuela. Available at: <http://www.worldbank.org/en/country/venezuela/overview>.

[62] Lander, E. (2016). pp. 2-3

[63] Gramer, R. (2017, January 26). Venezuela is so Broke it can’t even Export Oil. Foreign Policy.

[64] Gokay, B. (2017, April 10). Venezuela crisis is the hidden consequence of Saudi Arabia’s oil price war. Available at: <https://theconversation.com/venezuela-crisis-is-the-hidden-consequence-of-saudi-arabias-oil-price-war-82178>.

[65] Cunningham, N. (2017, August 8). Venezuela’s deteriorating crisis could send oil to $80 a barrel. Business Insider.

[66] Gallas, D. (2017, November 15). Russia and Venezuela agree debt deal. BBC News.

[67] De La Cruz, A. (2020, April 10). Rosneft’s Withdrawal amid U.S. Sanctions Contributes to Venezuela’s Isolation. Available at: <https://www.csis.org/analysis/rosnefts-withdrawal-amid-us-sanctions-contributes-venezuelas-isolation>.

[68] Negroponte, D. V. (2018, June 19). Russian Interests in Venezuela: A New Cold War? American Quarterly.

[69] De La Cruz, A. (2020, April 10).

[70] Labrador, R. C. (2019, February 5). Maduro’s Allies: Who Backs the Venezuelan Regime? Council on Foreign Relations. Available at: <https://www.cfr.org/in-brief/maduros-allies-who-backs-venezuelan-regime>.

[71] Negroponte, D. V. (2018, June 19).

[72] Guevara, C. (2020, January 13). China’s support for the Maduro regime: Enduring or fleeting? Atlantic Council.

[73] Hermoso, J., Fermin. V. (2019, January 14). Venezuela-China explained: The Belt and Road. SupChina.

[74] Rosales, A. (2018). Pursuing foreign investment for nationalist goals: Venezuela’s hybrid resource nationalism. Business and Politics, 443, Vol. 20, Issue 3, pp. 438-464.

[75] Kaplan, S. B., Penfold, M. (2019). China-Venezuela Economic Relations: Hedging Venezuelan Bets with Chinese Characteristics. 6, Wilson Center, Washington D.C: United States, pp. 1-40.

[76] Bull, W. (2008, September 25). Venezuela signs Chinese oil deal. BBC News.

[77] Plummer, R. (2013, March 5). Hugo Chavez leaves Venezuela in economic muddle. BBC News.

[78] Aizhu, C., Tan, F. (2018, June 15). Venezuela oil exports to China slump, may hit lowest in nearly 8 years: sources, data. Reuters.

[79] Suggett, J. (2010, August 4). Latest Venezuela-China Deals: Orinoco Agriculture, Civil Aviation, Steel, and $5 Billion Credit Line. Available at: <www.venezuelanalysis.com>.

[80] Kaplan, S. B., Penfold, M. (2019). p. 38.

[81] US Energy Information Administration. (2019, January 7).

[82] CRS. (2021). p. 22

[83] CRS, (2022).

[84] US Energy Information Administration, (2020).

[85] CRS, (2022).

[86] International Business Times News. (2022, March 31). Exclusive-Venezuela’s PDVSA Seeks Oil Tankers in Anticipation of US Sanctions Easing.

[87] Jaffe, A. M. (2018, January 23). How Much Worse Can It Get for Venezuela’s State Oil Firm PDVSA? Council on Foreign Relations. Available at: <https://www.cfr.org/blog/how-much-worse-can-it-get-venezuelas-state-oil-firm-pdvsa>.

[88] CRS, (2021), p. 11.

[89] CRS, (2021), p. 13.

[90] Vizcaino, M. E., Yapur, N. (2022, March 8). Defaulted Venezuela Bonds Are Luring Buyers Betting on US Deal. Bloomberg.

[91] Krauss, C. (2018, October 1). Venezuela’s Crisis Imperils Citgo, Its American ‘Cash Cow’. New York Times.

[92] Garip, P. (2021, August 12). Venezuela Negotiating Agenda in Crosscurrent. Argus Media.

[93] De La Cruz, A. (2020, April 10).

[94] Sigalos, M. (2019, February 7). China and Russia loaned billions to Venezuela — and then the presidency went up for grabs. CNBC.