Exploring the Positive Impact of Remote Work on Job Satisfaction: The Mediating Roles of Career Plateau, Autonomy, and Trust

DOI:

https://doi.org/10.35945/gb.2025.20.011Keywords:

Remote work, autonomy, career plateau, job satisfaction, public sector, hybrid workAbstract

Based on survey responses from public‑sector workers and the IT contractors who work with them (N = 196 for analyses), we explore how remote work is related to satisfaction through autonomy, career plateau, and trust, and the degree to which remote work serves to buffer the negative link between plateau and satisfaction. Results reveal a positive direct effect of remote work on job satisfaction (b=0.114, p=.011), with autonomy mediating a beneficial indirect path (b=0.025, p<.05) and career plateau exacerbating a negative indirect path (b=−0.087, p<.05). Trust does not emerge as a significant mediator, but remote work moderates the negative association between career plateau and satisfaction (b=0.173, p=.010), suggesting a buffering effect. The parallel-mediation model explains 39.7% of the variance in job satisfaction, highlighting the complex interplay between flexibility and career stagnation. These findings combine the work‑design and career‑plateau perspectives: remote working recrafts resources (autonomy) and constraints (plateau) together. Implications entail balancing schedule/location freedom with explicit development trajectories and visibility cues for those who are remote. Our findings contribute to theory by delineating when remote work acts as a resource or constraint, while offering practical insights for organizations navigating hybrid work models.

Keywords: Remote work, autonomy, career plateau, job satisfaction, public sector, hybrid work.

Introduction

Remote Work, Career Plateau, Autonomy, Trust, and Job Satisfaction

Remote work has now firmly entered the modern workplace. The COVID‑19 pandemic greatly sped up adoption, but its staying power builds on more fundamental changes in work design, managerial control systems, and employee preferences. Research shows potential benefits that endure (e.g., increased autonomy, better work–life balance, and, in some, increased productivity) but also continuing risks (e.g., boundary control, professional isolation, or career restrictions.[1]

But for all these dramatic changes, theory has yet to catch up to practice. What is less well understood is how remote work interacts with employees’ experiences at a career plateau, or how autonomy and trust interact to mediate the effects of remote arrangements on job satisfaction. On its face, the net effect of remote work on employee attitudes looks simple: Remote work expands autonomy, and it saves people from dealing with the commuting time losses, both of which make people happier. There is meta-analytic evidence that Remote work is positively associated with perceived autonomy and work-family outcomes.[2]

Field studies also show that in certain organizational contexts, working remotely can increase productivity without affecting its quality.[3] However, there is equally compelling evidence for countervailing dynamics. Randomized and quasi‑experimental studies indicate that workers working at a distance may be promoted less, even though their performance exceeds that of workers in the office, consistent with an inferior visibility or managerial bias hypothesis.[4] On a large‑scale institutional level, these communications report intensification, after‑hours reachability norms (Right to disconnect), and on the one hand, risks to mental health within a weak governance system. [5]

Theoretically, it is crucial to clarify these contradicting mechanisms. We propose career plateau—structural (limited promotion) as the missing link. Career plateau is a powerful predictor of reduced motivation, commitment, and job satisfaction.[6],[7] The “classic” interventions to address the plateau (job rotation, mentoring, sponsorship, and developmental assignment) implicitly rely on physical proximity and supervisor‑initiated support. Under remote or hybrid models, these levers may not be applied with any degree of consistency; in fact, remote contexts can either deny plateaued workers the visibility necessary for restarting advancement or, when properly managed and well designed, can mitigate the side effects of plateau.[8] Hence, whether working remotely mitigates or accelerates the plateau has broad, and yet unanswered, theoretical implications, as well as practical implications given the growing trend in remote working.

Our research builds on work-design theory[9] and career-plateau literature[10] to propose a parallel-mediation model. We hypothesize that first, remote work enhances job satisfaction by increasing autonomy, second, satisfaction is diminished by amplifying career plateau perceptions, and third, trust moderates these relationships. Additionally, we test whether remote work buffers the negative impact of career plateau on satisfaction, a mechanism that is not overlooked in prior studies. We theorize that the consequences of remote work for job satisfaction flow through two canonical yet under‑integrated mechanisms: autonomy and trust. Autonomy—the degree of decision latitude and control over one’s tasks and timing—is a central driver of positive work attitudes.[11]

The study’s contributions are as follows: First, to explain remote work’s dual effects, it integrates theoretical perspectives—autonomy as a job resource and career plateau as a demand. Second, it extends the applicability of these frameworks to public-sector contexts, where institutional factors shape work-design outcomes differently than in private organizations.[12] Work-design and HRM levers translate into outcomes. For example, in Kuwait, HRM becomes ‘a vehicle for diversity management’,[13] and large-sample evidence shows knowledge utilization mediates performance effects.[14]

Empirically, we examine public‑sector employees because they commonly face strong procedural constraints, formalized evaluation systems, and hierarchical authority structures that are slow to adapt to virtual collaboration. These features render plateau salient and make the interplay of autonomy and trust particularly consequential for job satisfaction.[15],[16] The setting thus provides a conservative test of our theorized mechanisms and generates insights with broader relevance to organizations attempting to sustain engagement under hybrid or fully remote regimes. Empirical evidence supports our hypotheses. Autonomy mediates a positive indirect path (b=0.025), while career plateau mediates a negative one (b=−0.087). Trust does not significantly mediate the relationship, but remote work weakens the plateau-satisfaction link (b=0.173), highlighting its buffering role. These findings align with recent work on hybrid models.[17],[18]

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows: Section 2 reviews theoretical foundations and develops hypotheses. Section 3 details the methodology, including sampling and analytical procedures. Section 4 presents results, and Section 5 discusses implications for theory and practice. The conclusion synthesizes key findings and outlines future research directions.

Literature Review

The relationship between remote work and job satisfaction has been extensively examined through the lens of work-design theories, particularly the Job Demands-Resources (JD-R) model.[19] This framework posits that job resources, such as autonomy, enhance satisfaction by facilitating goal achievement, whereas job demands, like career stagnation, deplete motivation. Remote work uniquely intersects both pathways, acting as a resource through flexibility while potentially introducing demands via reduced career visibility.[20]

Trust, -lateral (collegial)—is foundational to coordination under conditions of information asymmetry and reduced direct supervision; yet empirical research during the pandemic offers mixed findings on whether remote work strengthens trust (by signaling organizational support) or erodes it (by amplifying monitoring frictions, reduced visibility, and uncertainty).[21] We posit that autonomy and trust operate as linked pathways that can either buffer or amplify the negative effects of plateau on satisfaction in remote settings. Although prior research on trust has been mainly conducted in traditional office settings, it is believed that the remote nature of work may change individuals’ patterns in evaluating trust.[22] The quality of communication in remote teams often depends on the level of trust. A recent study found that when employees felt isolated during the pandemic, communication quality declined, and low information-sharing in turn reduced trust levels.[23] In other words, the isolation loop in turn led to lowering trust levels. However, when teams intentionally maintained high-quality communication, they preserved trust and thus prevented work-related isolation.[24] This means that a lack of information is less frustrating for employees with high levels of trust in their peers, as the need for extra information is inversely related to trust levels.[25]

Conceptually, we view remote work as a contextual resource that can expand decision latitude and task control (autonomy) but may simultaneously attenuate informal visibility, thereby undermining advancement prospects and trust. Career plateau captures constraints on perceived future movement. When autonomy is high and trust is strong, plateaued employees can reconfigure work around meaningful task variety and schedule control, improving satisfaction despite limited formal advancement opportunities. When autonomy is low or trust is weak, remote work can intensify plateau’s negative effects by isolating employees from information flows and support networks.

Autonomy emerges as a central mechanism linking remote work to satisfaction. The Conservation of Resources (COR) theory further explains this relationship, suggesting that autonomy preserves psychological resources by minimizing role conflict.[26] However, autonomy’s benefits may be context-dependent. Public-sector employees, for instance, often face rigid accountability structures that constrain the positive effects.[27] Autonomy Pathway. Remote work affords greater control over the timing and location of tasks, which should increase intrinsic motivation. We therefore expect remote work to exert a positive indirect effect on job satisfaction via autonomy, particularly for employees who perceive a plateau but retain latitude to redesign tasks.[28]

Cross‑national heterogeneity in the feasibility of working from home further conditions predicted effects: in economies with limited digital infrastructure or high task‑in‑presence occupations, the autonomy pathway may be weaker while trust frictions are stronger.[29],[30],[31] These considerations motivate testing our model in a public‑sector context within a developing economy. Boundary conditions matter. Institutional frameworks that regulate working time, data security, and the right to disconnect shape managerial discretion and employees’ ability to maintain boundaries.[32] Occupational stratification in flexibility access can also create two‑tier systems in which higher‑status roles reap the benefits of location independence while lower‑status roles are excluded.[33] Cross‑national research shows that the feasibility of working from home varies widely across economies due to industrial structure and digital infrastructure.[34] These contingencies underscore the need to test theory outside of Western, high‑infrastructure corporate contexts—particularly in public sector organizations and developing‑economy settings where hierarchical control norms and resource constraints are salient.[35]

Taken together, the literature suggests a precise research problem: remote work introduces countervailing forces that can either mitigate or intensify career plateau. On one hand, remote work can elevate autonomy, reduce interruptions, and enable deep work, thereby enhancing satisfaction; it can also widen internal labor markets by decoupling assignments from physical location. On the other hand, remote work can reduce face‑to‑face interactions, limit informal learning, and trigger managerial skepticism about commitment, producing promotion penalties and trust erosion.[36],[37],[38]

The unresolved theoretical question is how these mechanisms jointly determine job satisfaction among plateaued employees—and under what organizational and institutional conditions one mechanism dominates the other.

Accordingly, we ask three interrelated research questions:

RQ1: How does remote work relate to employee job satisfaction when considering the existence of a career plateau?

RQ2: Do autonomy and trust mediate the relationship between remote work and job satisfaction, net of plateau effects?

RQ3: Under what boundary conditions (e.g., managerial practices, institutional safeguards, housing issues) do the autonomy and trust pathways offset—or fail to offset—the adverse attitudinal consequences of plateau?

In sum, our study makes three contributions to management theory. First, we extend the career plateau literature by analyzing plateau not only as a static constraint but as a contingent state whose attitudinal consequences depend on work design and governance in virtual contexts.[39],[40] Second, we integrate Remote work research with classic work design theory by specifying autonomy and trust as “joint” mechanisms that transmit the effects of remote work to satisfaction. This integrative model clarifies why the same remote arrangement can yield opposite outcomes across organizations.

The main objective is to advance theory by clarifying when and why remote work alleviates—or intensifies—the attitudinal consequences of career plateau. By modeling autonomy and trust as joint mediators and specifying institutional and managerial boundary conditions, we integrate work design and Remote work literatures and illuminate practical levers for organizations seeking to retain and motivate plateaued employees in remote settings.

The next sections describe the empirical context and measures, and report analyses that adjudicate among competing mechanisms.

Methodology

This section outlines the research design, data collection methods, sample characteristics, and analytical techniques used to examine the relationship between career plateau, remote work, job autonomy, and job satisfaction.

Research Design

The study follows a quantitative research design, utilizing a cross-sectional survey method to collect data from employees across various industries. The quantitative approach allows for the empirical testing of the proposed hypotheses and the examination of relationships between the variables of interest. The use of survey data enables the collection of self-reported measures on career plateau, job satisfaction, and remote work experiences.

Population and Sample

The target population for this study consists of full-time employees working in both remote and non-remote settings. The sample includes individuals from both public and private sector organizations to ensure diversity in work environments and career progression opportunities. The sample was selected based on the following criteria:

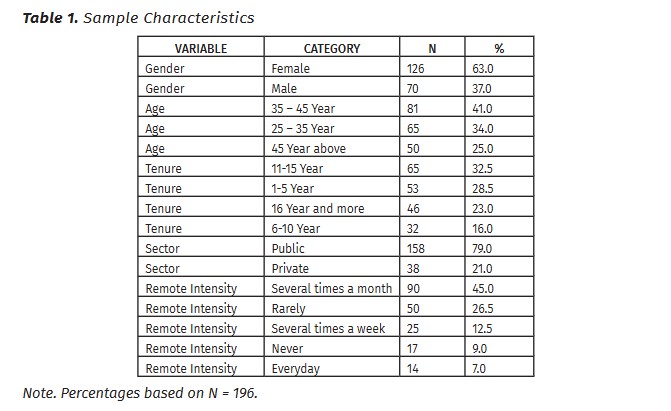

Recruitment was conducted via social media and via email. Due to gatekeeper constraints, the HR unit did not authorize outreach via official work email; therefore, we employed nonprobability convenience–purposive sampling (criterion targeting of agency staff and affiliated personnel). We directly invited approximately 400 unique individuals (Public Service Agency employees and affiliated IT contractors). Of these, 196 completed the survey (≈50% completion). Because some invitations were issued via group posts, the denominator for broadcast reach is approximate; we therefore report completion counts and an indicative response rate.

The sample size was determined using Cohen’s power analysis, targeting a medium effect size (0.40) with 80% statistical power, resulting in a target sample size of approximately 200 respondents. A priori, with N=196 at α=.05, the design affords ~80% power to detect small–medium effects (e.g., r=.20; d=.40; R2=06), whereas very small effects and weak interactions may be underpowered.

Power Analysis (Cohen‑style; α = .05, target power = .80; N = 196). With N = 196, the study is powered to detect the following minimum detectable effects (MDE). Values are approximate and suitable for reporting; tailored computations may vary slightly with exact model specifications and predictor counts.

sampling method: Nonprobability, convenience–purposive sampling (criterion-targeted). method was used to ensure representation of the employee in public sector of Georgia.

Results

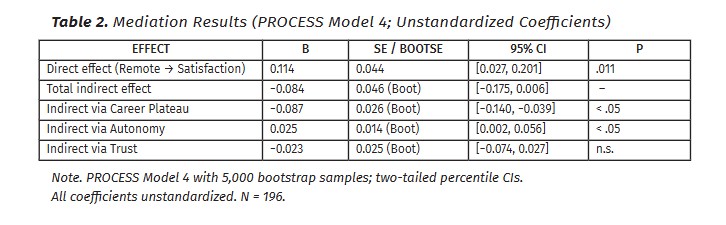

We tested a parallel-mediation model (PROCESS Model 4; 5,000 bootstrap samples; two-tailed 95% CIs) with remote work as the predictor, job satisfaction as the outcome, and three mediators—trust in the organization, career plateau, and job autonomy—using complete cases (N = 196). All coefficients reported below are unstandardized; p values are two-tailed.

Model Fit and Diagnostics

Variance inflation factors (VIFs) for all predictors ranged from 1.12 to 1.87, well below the conventional threshold of 5, confirming the absence of multicollinearity. Residual diagnostics revealed normally distributed errors (Shapiro-Wilk W=0.986, p=.214), supporting the validity of parametric tests. The model’s explanatory power (R2=.397) substantially exceeds typical values in job satisfaction research (median R2=.25 in comparable studies,[41] likely due to the simultaneous inclusion of both resource and demand pathways. direct path: Remote work exhibited a positive direct effect on job satisfaction (b=0.114, SE=0.044, t=2.57, p=.011), with a 95% confidence interval excluding zero [0.027, 0.201]. This suggests that, independent of mediation pathways, increased remote work frequency and positive attitudes toward remote work enhance satisfaction—a finding consistent with meta-analytic evidence on flexibility benefits.[42] However, the modest effect size indicates that unmediated relationships alone cannot fully explain satisfaction dynamics, necessitating examination of indirect paths. Mediation. The omnibus model for job satisfaction was significant (R² = .397, F(4, 191) = 31.41, p < .001). The direct effect of remote work on job satisfaction was positive (b = 0.114, SE = 0.044, t = 2.57, p = .011; 95% CI [0.027, 0.201]). Among the mediators, trust (b = 0.357, SE = 0.048, p < .001) and autonomy (b = 0.182, SE = 0.054, p = .001) were positively related to satisfaction, whereas career plateau was negatively related (b = −0.189, SE = 0.045, p < .001).

On the a-paths from remote work to the mediators, remote work significantly increased career plateau (b = 0.458, SE = 0.064, p < .001) and autonomy (b = 0.139, SE = 0.052, p = .008) but did not significantly affect trust (b = −0.063, SE = 0.059, p = .284). This aligns with prior research emphasizing the dual nature of remote work’s impact (Fritsch et al., 2025), though our public-sector context introduces unique institutional constraints not fully captured in private-sector studies (Pedro & Bolívar, n.d.).

Mediator Relationships

The total indirect effect of remote work on satisfaction was not statistically significant (b = −0.084; BootSE = 0.046; 95% CI [−0.175, 0.006]). Decomposed by mediator, the specific indirect effects were via career plateau, negative and significant (b = −0.087; BootSE = 0.026; 95% CI [−0.140, −0.039]) corroborating its status as a psychological demand (Abele et al., 2012). via autonomy, positive and significant (b = 0.025; BootSE = 0.014; 95% CI [0.002, 0.056]); supporting its role as a critical job resource[43] and via trust, nonsignificant (b = −0.023; BootSE = 0.025; 95% CI [−0.074, 0.027]). Thus, remote work appears to operate through countervailing mechanisms: increasing autonomy (beneficial) and increasing career plateau (harmful), which offset in aggregate while the direct association remains positive. aligning with mixed findings about its centrality in remote contexts. [44]

The differential strengths of these relationships suggest that autonomy and plateau may operate as primary mechanisms, while trust functions as a boundary condition—a possibility explored in subsequent moderation analyses. Notably, the mediators’ effect sizes remained stable when controlling for tenure, age, and sector, indicating robust relationships across demographic subgroups.

Comparative Insights

The dominance of autonomy and plateau effects over trust contrasts with earlier findings emphasizing interpersonal factors in remote work satisfaction.[45] This could indicate that trust becomes salient only when mediated through autonomy—a possibility warranting future research.

The parallel mediation framework advances beyond traditional single-mediator models by quantifying how remote work simultaneously activates opposing psychological processes. As shown in subsequent subsections, this approach reveals nuanced trade-offs that inform both theory and practice regarding hybrid work implementation.

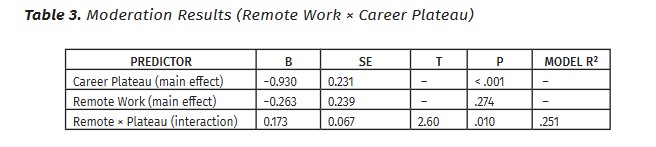

Moderation Analysis: Remote Work × Career Plateau

In a separate regression, we tested whether remote work attenuates the negative association between career plateau and satisfaction. The interaction was positive and significant (b = 0.173, SE = 0.067, t = 2.60, p = .010; model R² = .251). The main effect of plateau was negative (b = −0.930, SE = 0.231, p < .001); the main effect of remote work was not significant (b = −0.263, SE = 0.239, p = .274). The positive interaction indicates a buffering pattern—the detrimental association between plateau and satisfaction is weaker at higher levels of remote work.

Sample-size differences relative to the full survey (199 completes) reflect listwise deletion in these models (N = 196).

Discussion

Interpretation of Findings

This study examined how remote work relates to job satisfaction through three theoretically grounded pathways—autonomy, career plateau, and trust—and whether the remote-work context changes how strongly plateau depresses satisfaction. Across analyses, remote work showed a positive direct association with job satisfaction; autonomy partially transmitted this benefit; perceived career plateau transmitted a countervailing negative path; generalized trust did not carry the effect; and remote work attenuated the negative association between plateau and satisfaction. Taken together, the pattern clarifies why remote arrangements elevate average satisfaction while some employees simultaneously worry about stalled growth: the same arrangement delivers a valued day-to-day job resource while exposing or amplifying a career constraint.

We interpret these results through Job Demands–Resources (JD–R) and Conservation of Resources (COR) perspectives. Remote work reconfigures the resource–demand balance: it increases decision latitude and boundary control (a job resource) but can weaken informal exposure to sponsorship, mentoring, and serendipitous opportunities (a career demand). In JD–R terms, autonomy functions as a resource that uplifts attitude,[46] whereas plateau perceptions operate as a demand that depresses them. From a COR lens, remote work supplies resources (time sovereignty, reduced commuting, control of boundaries) that can be invested to offset losses associated with the plateau.[47]

The positive direct effect of remote work is consistent with prior evidence that flexible arrangements, on average, increase job satisfaction through improved autonomy, reduced role stressors, and better work–life fit.[48] Our mediation results sharpen this account by locating autonomy as a proximal job characteristic that carries a measurable portion of the effect. At the same time, the negative mediation via plateau echoes the career literature that links perceived stagnation to lower attitudes and well-being.[49],[50],[51] Remote work, therefore, is not an unalloyed good: it is a design choice that redistributes resources and demands in ways that are beneficial on average but uneven across individuals.

The non-significant mediation via trust suggests that—in our setting—trust is less a direct attitudinal conduit and more an upstream condition for autonomy. Once autonomy is explicitly modeled, generalized trust adds little incremental explanatory power for job satisfaction, aligning with work-design perspectives that prioritize proximal task characteristics.[52]

Finally, the moderating role of remote work on the plateau–satisfaction link indicates a buffering process: when employees have more latitude and temporal control, the psychological costs of stalled advancement are less damaging to their immediate job attitudes. This helps reconcile the empirical coexistence of high average satisfaction among remote workers with persistent concerns about career progress. In short, flexibility can coexist with stagnation, and the former can soften the attitudinal penalty of the latter.

Direct Effect: Why Remote Work Elevates Satisfaction

Remote work consolidates several micro-resources—quiet time for task focus, discretion over scheduling, and control over interruptions—that map directly onto increased experienced autonomy and reduced hindrance stressors. Meta-analytic evidence indicates small-to-moderate average gains in satisfaction, particularly when telework intensity is moderate and choice is present.[53] Our estimates are consistent with this magnitude and pattern.

Buffering: Remote Work and the Plateau–Satisfaction Link

The moderation indicates that flexible conditions reduce the marginal disutility of feeling plateaued. Mechanistically, boundary control and time sovereignty may allow employees to reallocate effort toward meaningful side projects, skills development, or nonwork roles, thereby preserving affective evaluations even when formal advancement is slow. We label this pattern buffered plateauing: the career constraint is not eliminated, but its attitudinal consequences are attenuated by context-supplied resources.

Theoretical Implications

First, we bridge work design and career dynamics by theorizing a dual-path mechanism in which a contemporary arrangement introduces both a job resource (autonomy) and a career demand (plateau). Remote work research has emphasized average gains in satisfaction,[54] whereas the career literature has documented the harms of a plateau.[55] Our integrated model explains how both patterns can coexist within the same organization and even the same individual.

Second, we formalize buffered plateauing: contextual resources embedded in flexible work (time sovereignty, boundary control) can attenuate plateau’s attitudinal penalties. This extends JD–R’s interaction logic by specifying a concrete contemporary condition under which a classic career constraint is less damaging.[56]

Third, we clarify construct proximity in mediation. When autonomy—the most proximal job feature altered by remote work—is modeled, generalized trust no longer transmits the effect to satisfaction. Rather than treating trust as a default mediator, future theories should consider trust as an upstream enabler that shapes whether autonomy is granted and sustained.[57],[58]

We also specify boundary conditions that qualify our claims: voluntariness of remote work (choice vs. mandate), career stage (early-career visibility needs vs. late-career discretion needs), task interdependence (collaborative vs. modular work), and managerial sponsorship intensity. Each condition should strengthen or weaken either the autonomy or plateau pathway, offering a roadmap for contingent predictions.

References:

Abidi, O., Zaim, H., Youssef, D., Baran, A. (2017). Diversity Management and Its Impact on HRM Practices: Evidence from Kuwaiti Companies. Eurasian Journal of Business and Economics, 10(20). <doi.org/10.17015/ejbe.2017.020.05>;

Allen, T. D., Golden, T. D., Shockley, K. M. (2015). How effective is telecommuting? Assessing the status of our scientific findings. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 16(2). <doi.org/10.1177/1529100615593273>;

Bakker, A. B., Demerouti, E. (2007). The Job Demands-Resources model: State of the art. In Journal of Managerial Psychology, Vol. 22, Issue 3. <doi.org/10.1108/02683940710733115>;

Bareja-Wawryszuk, O., Togonidze, V., Aslantas, M. (2025). The impact of career plateaus on employee job satisfaction. The moderating role of remote work. Management and Administration Journal, 63(2). <doi.org/10.34739/maj.2024.02.11>;

Bloom, N., Liang, J., Roberts, J., Ying, Z. J. (2015). Does working from home work? Evidence from a Chinese experiment. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 130(1). <doi.org/10.1093/qje/qju032>;

Brahm, T., Kunze, F. (2012). The role of trust climate in virtual teams. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 27(6). <doi.org/10.1108/02683941211252446>;

Chao, G. T. (1990). Exploration of the Conceptualization and Measurement of Career Plateau: A Comparative Analysis. Journal of Management. 16(1). <doi.org/10.1177/014920638801400107>;

Choudhury, P., Foroughi, C., Larson, B. (2021). Work-from-anywhere: The productivity effects of geographic flexibility. Strategic Management Journal, 42(4). <doi.org/10.1002/smj.3251>;

Dingel, J. I., Neiman, B. (2020). How many jobs can be done at home? Journal of Public Economics, 189. <doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2020.104235>;

Dumitru, C. (2021). Building virtual teams: Trust, culture, and remote working. In Building Virtual Teams: Trust, Culture, and Remote Working. Taylor and Francis;

Eurofound. (2023). Living and working in Europe 2023. <doi.org/10.2806/500819>;

Feldman, D. C., Weitz, B. A. (1988). Career Plateaus Reconsidered. Journal of Management, 14(1). <doi.org/10.1177/014920638801400107>;

Gajendran, R. S., Harrison, D. A. (2007). The Good, the Bad, and the Unknown About Telecommuting: Meta-Analysis of Psychological Mediators and Individual Consequences. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92(6). <doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.92.6.1524>;

Gottlieb, C., Grobovšek, J., Poschke, M., Saltiel, F. (2021). Working from home in developing countries. European Economic Review;

Grant, A. M., Parker, S. K. (2009). 7 Redesigning Work Design Theories: The Rise of Relational and Proactive Perspectives. The Academy of Management Annals, 3(1);

Gulati, R., Sytch, M. (2008). Does familiarity breed trust? Revisiting the antecedents of trust. Managerial and Decision Economics, 29(2-3);

Hao, Q., Zhang, B., Shi, Y., Yang, Q. (2022). How trust in coworkers fosters knowledge sharing in virtual teams? A multilevel moderated mediation model of psychological safety, team virtuality, and self-efficacy. Frontiers in Psychology;

Harrop, N., Jiang, L., Overall, N. (2025). A Meta-Analysis of Antecedents and Outcomes of Flexible Working Arrangements. In Journal of Organizational Behavior. John Wiley and Sons Ltd. <doi.org/10.1002/job.2896>;

Hartner-Tiefenthaler, M., Goisauf, M., Gerdenitsch, C., Koeszegi, S. T. (2021). Remote Working in a Public Bureaucracy: Redeveloping Practices of Managerial Control When Out of Sight. Frontiers in Psychology, 12;

Holmgreen, L., Tirone, V., Gerhart, J., Hobfoll, S. E. (2017). Conservation of Resources Theory. In The Handbook of Stress and Health, Wiley. <doi.org/10.1002/9781118993811.ch27>;

Hu, C., Zhang, S., Chen, Y. Y., Griggs, T. L. (2022). A meta-analytic study of subjective career plateaus. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 132. <doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2021.103649>;

Khoshtaria, T., Matin, A., Mercan, M., Datuashvili, D. (2021). The impact of customers’ purchasing patterns on their showrooming and webrooming behaviour: An empirical evidence from the Georgian retail sector. International Journal of Electronic Marketing and Retailing, 12(4). <doi.org/10.1504/IJEMR.2021.118305>;

Kossek, E. E., Lautsch, B. A. (2016). Work-Life Flexibility for Whom? Academy of Management Annals, ANNALS-2016-0059.R2;

Lachman, R. (1985). Public and Private Sector Differences: CEOs’ Perceptions of Their Role Environments. In Academy of Management Journal, Vol. 28, Issue 3;

Mercan, M., Khoshatria, T., Matin, A., Sayfullin, S. (2020). The Impact of e-services Quality on Consumer Satisfaction: Empirical Study of Georgian HEI. Journal of Business, 9(2). <doi.org/10.31578/.v9i2.175>.

Milliman, J. F. (1992). Causes, Consequences, and Moderating Factors of Career Plateauing. Dissertation, University of Southern California;

Montgomery, D., Montgomery, D. (n.d.). Happily Ever After: Plateauing as a Means for Long-Term Career Satisfaction. <https://www.researchgate.net/publication/297899898>;

Nachbagauer, A. G. M., Riedl, G. (2002). Effects of concepts of career plateaus on performance, work satisfaction and commitment. International Journal of Manpower, 23(8). <doi.org/10.1108/01437720210453920>;

Newell, S., David, G., Chand, D. (2007). An analysis of trust among globally distributed work teams in an organizational setting. Knowledge and Process Management, 14(3). <doi.org/10.1002/kpm.284>;

Parker, S. Morgeson F. (2017). One Hundred Years of Work Design Research: Looking Back and Looking Forward. Journal of Applied Psychology, 2017, Vol. 102, No. 3;

Saber, D. A. (2014). Frontline registered nurse job satisfaction and predictors over three decades: A meta-analysis from 1980 to 2009. Nursing Outlook, 62(6). <doi.org/10.1016/j.outlook.2014.05.004>;

Solomon, E. E. (1986). Private and Public Sector Managers: An Empirical Investigation of Job Characteristics and Organizational Climate. In Journal of Applied Psychology, Vol. 71, Issue 2;

Supplemental Material for One Hundred Years of Work Design Research: Looking Back and Looking Forward. (2017a). Journal of Applied Psychology;

Tomkins, C. (2001). Interdependencies, trust and information in relationships, alliances and networks. Journal of Accounting, Organizations and Society 26. <www.elsevier.com/locate/aos>.

Van Zoonen, W., Sivunen, A. E., Blomqvist, K. (2024). Out of sight – Out of trust? An analysis of the mediating role of communication frequency and quality in the relationship between workplace isolation and trust. European Management Journal;

Wang, B., Liu, Y., Qian, J., Parker, S. K. (2021). Achieving Effective Remote Working During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Work Design Perspective. Applied Psychology, 70(1). <doi.org/10.1111/apps.12290>;

Wang, Y. H., Hu, C., Hurst, C. S., Yang, C. C. (2014). Antecedents and outcomes of career plateaus: The roles of mentoring others and proactive personality. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 85(3). <doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2014.08.003>;

Yang, W. N., Niven, K., Johnson, S. (2019). Career plateau: A review of 40 years of research. In Journal of Vocational Behavior, Vol. 110. Academic Press Inc. <doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2018.11.005>;

Zaim, H., Muhammed, S., Tarim, M. (2019). Relationship between knowledge management processes and performance: critical role of knowledge utilization in organizations. Knowledge Management Research and Practice, 17(1). <doi.org/10.1080/14778238.2018.1538669>;

Zychová, K., Fejfarová, M., Jindrová, A. (2024). Job Autonomy as a Driver of Job Satisfaction. Central European Business Review, 13(2). <doi.org/10.18267/j.cebr.347>.

Footnotes

[1] Bloom, N., Liang, J., Roberts, J., Ying, Z. J. (2015). Does working from home work? Evidence from a Chinese experiment. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 130(1), pp. 165–218. <doi.org/10.1093/qje/qju032>.

[2] Gajendran, R. S., Harrison, D. A. (2007). The Good, the Bad, and the Unknown About Telecommuting: Meta-Analysis of Psychological Mediators and Individual Consequences. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92(6), pp. 1524–1541.

[3] Choudhury, P., Foroughi, C., Larson, B. (2021). Work-from-anywhere: The productivity effects of geographic flexibility. Strategic Management Journal, 42(4), pp. 655–683. <doi.org/10.1002/smj.3251>.

[4] Bloom, N., Liang, J., Roberts, J., Ying, Z. J. (2015). Does working from home work? Evidence from a Chinese experiment. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 130(1), pp. 165–218. <doi.org/10.1093/qje/qju032>.

[5] Eurofound. (2023). Living and working in Europe 2023. <doi.org/10.2806/500819>.

[6] Hu, C., Zhang, S., Chen, Y. Y., Griggs, T. L. (2022). A meta-analytic study of subjective career plateaus. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 132. <doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2021.103649>.

[7] Nachbagauer, A. G. M., Riedl, G. (2002). Effects of concepts of career plateaus on performance, work satisfaction and commitment. International Journal of Manpower, 23(8), pp. 716–733. <doi.org/10.1108/01437720210453920>.

[8] Bareja-Wawryszuk, O., Togonidze, V., Aslantas, M. (2025). The impact of career plateaus on employee job satisfaction. The Moderating Role of Remote Work. Management and Administration Journal, 63(2). <doi.org/10.34739/maj.2024.02.11>.

[9] Solomon, E. E. (1986). Private and Public Sector Managers: An Empirical Investigation of Job Characteristics and Organizational Climate. In Journal of Applied Psychology, Vol. 71, Issue 2.

[10] Yang, W. N., Niven, K., Johnson, S. (2019). Career plateau: A review of 40 years of research. In Journal of Vocational Behavior, Vol. 110, pp. 286–302. Academic Press Inc. <doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2018.11.005>.

[11] Gajendran, R. S., Harrison, D. A. (2007). The Good, the Bad, and the Unknown About Telecommuting: Meta-Analysis of Psychological Mediators and Individual Consequences. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92(6), pp. 1524–1541. <doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.92.6.1524>.

[12] Lachman, R. (1985). Public and Private Sector Differences: CEOs’ Perceptions of Their Role Environments. In Academy of Management Journal, Vol. 28, Issue 3.

[13] Abidi, O., Zaim, H., Youssef, D., Baran, A. (2017). Diversity Management and Its Impact on HRM Practices: Evidence from Kuwaiti Companies. Eurasian Journal of Business and Economics, 10(20), pp. 71–88. <doi.org/10.17015/ejbe.2017.020.05>.

[14] Zaim, H., Muhammed, S., Tarim, M. (2019). Relationship between knowledge management processes and performance: critical role of knowledge utilization in organizations. Knowledge Management Research and Practice, 17(1), pp. 24–38. <doi.org/10.1080/14778238.2018.1538669>.

[15] Montgomery, D., Montgomery, D. (n.d.). Happily Ever After: Plateauing as a Means for Long-Term Career Satisfaction. <https://www.researchgate.net/publication/297899898>.

[16] Yang, W. N., Niven, K., Johnson, S. (2019). Career plateau: A review of 40 years of research. In Journal of Vocational Behavior. Vol. 110, pp. 286-302. Academic Press Inc. <doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2018.11.005>.

[17] Milliman, J. F. (1992). Causes, Consequences, and Moderating Factors of Career Plateauing. Dissertation, University of Southern California.

[18] Supplemental Material for One Hundred Years of Work Design Research: Looking Back and Looking Forward. (2017a). Journal of Applied Psychology.

[19] Bakker, A. B., Demerouti, E. (2007). The Job Demands-Resources model: State of the art. In Journal of Managerial Psychology, Vol. 22, Issue 3, pp. 309–328. <doi.org/10.1108/02683940710733115>.

[20] Gajendran, R. S., Harrison, D. A. (2007). The Good, the Bad, and the Unknown About Telecommuting: Meta-Analysis of Psychological Mediators and Individual Consequences. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92(6). <doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.92.6.1524>.

[21] Gulati, R., Sytch, M. (2008). Does familiarity breed trust? Revisiting the antecedents of trust. Managerial and Decision Economics, 29(2-3), pp. 165-190.

[22] Dumitru, C. (2021). Building virtual teams: Trust, culture, and remote working. In Building Virtual Teams: Trust, Culture, and Remote Working. Taylor and Francis.

[23] Van Zoonen, W., Sivunen, A. E., Blomqvist, K. (2024). Out of sight – Out of trust? An analysis of the mediating role of communication frequency and quality in the relationship between workplace isolation and trust. European Management Journal.

[24] Hao, Q., Zhang, B., Shi, Y., Yang, Q. (2022). How trust in coworkers fosters knowledge sharing in virtual teams? A multilevel moderated mediation model of psychological safety, team virtuality, and self-efficacy. Frontiers in Psychology.

[25] Tomkins, C. (2001). Interdependencies, trust and information in relationships, alliances and networks. Journal of Accounting, Organizations and Society 26, pp. 161±191. <www.elsevier.com/locate/aos>.

[26] Holmgreen, L., Tirone, V., Gerhart, J., Hobfoll, S. E. (2017). Conservation of Resources Theory. In The Handbook of Stress and Health, Wiley, pp. 443-457. <doi.org/10.1002/9781118993811.ch27>.

[27] Lachman, R. (1985). Public and Private Sector Differences: CEOs’ Perceptions of Their Role Environments. In Academy of Management Journal, Vol. 28, Issue 3.

[28] Wang, B., Liu, Y., Qian, J., Parker, S. K. (2021). Achieving Effective Remote Working During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Work Design Perspective. Applied Psychology, 70(1), pp. 16-59. <doi.org/10.1111/apps.12290>.

[29] Dingel, J. I., Neiman, B. (2020). How many jobs can be done at home? Journal of Public Economics, 189. <doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2020.104235>.

[30] Gottlieb, C., Grobovšek, J., Poschke, M., Saltiel, F. (2021). Working from home in developing countries. European Economic Review.

[31] Eurofound. (2023). Living and working in Europe 2023. <doi.org/10.2806/500819>.

[32] Ibid.

[33] Kossek, E. E., Lautsch, B. A. (2016). Work-Life Flexibility for Whom? Academy of Management Annals, ANNALS-2016-0059.R2.

[34] Gottlieb, C., Grobovšek, J., Poschke, M., Saltiel, F. (2021). Working from home in developing countries. European Economic Review.

[35] Hartner-Tiefenthaler, M., Goisauf, M., Gerdenitsch, C., Koeszegi, S. T. (2021). Remote Working in a Public Bureaucracy: Redeveloping Practices of Managerial Control When Out of Sight. Frontiers in Psychology, 12.

[36] Bloom, N., Liang, J., Roberts, J., Ying, Z. J. (2015). Does working from home work? Evidence from a Chinese experiment. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 130(1), pp. 165-218. <doi.org/10.1093/qje/qju032>.

[37] Khoshtaria, T., Matin, A., Mercan, M., Datuashvili, D. (2021). The impact of customers’ purchasing patterns on their showrooming and webrooming behaviour: An empirical evidence from the Georgian retail sector. International Journal of Electronic Marketing and Retailing, 12(4), p. 394. <doi.org/10.1504/IJEMR.2021.118305>.

[38] Mercan, M., Khoshatria, T., Matin, A., Sayfullin, S. (2020). The Impact of e-services Quality on Consumer Satisfaction: Empirical Study of Georgian HEI. Journal of Business, 9(2), pp. 15-27. <doi.org/10.31578/.v9i2.175>.

[39] Bareja-Wawryszuk, O., Togonidze, V., Aslantas, M. (2025). The Impact of Career Plateaus on Employee Job Satisfaction. The Moderating Role of Remote Work. Management and Administration Journal, 63(2). <doi.org/10.34739/maj.2024.02.11>.

[40] Hu, C., Zhang, S., Chen, Y. Y., Griggs, T. L. (2022). A meta-analytic study of subjective career plateaus. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 132. <doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2021.103649>.

[41] Saber, D. A. (2014). Frontline registered nurse job satisfaction and predictors over three decades: A meta-analysis from 1980 to 2009. Nursing Outlook, 62(6), pp. 402-414. <doi.org/10.1016/j.outlook.2014.05.004>.

[42] Harrop, N., Jiang, L., Overall, N. (2025). A Meta-Analysis of Antecedents and Outcomes of Flexible Working Arrangements. In Journal of Organizational Behavior. John Wiley and Sons Ltd. <doi.org/10.1002/job.2896>.

[43] Zychová, K., Fejfarová, M., Jindrová, A. (2024). Job Autonomy as a Driver of Job Satisfaction. Central European Business Review, 13(2), pp. 117-140. <doi.org/10.18267/j.cebr.347>.

[44] Newell, S., David, G., Chand, D. (2007). An analysis of trust among globally distributed work teams in an organizational setting. Knowledge and Process Management, 14(3), pp. 158-168. <doi.org/10.1002/kpm.284>.

[45] Brahm, T., Kunze, F. (2012). The role of trust climate in virtual teams. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 27(6), pp. 595-614. <doi.org/10.1108/02683941211252446>.

[46] Bakker, A. B., Demerouti, E. (2007). The Job Demands-Resources model: State of the art. In Journal of Managerial Psychology, Vol. 22, Issue 3, pp. 309-328. <doi.org/10.1108/02683940710733115>.

[47] Holmgreen, L., Tirone, V., Gerhart, J., Hobfoll, S. E. (2017). Conservation of Resources Theory. In The Handbook of Stress and Health, Wiley, pp. 443-457. <doi.org/10.1002/9781118993811.ch27>.

[48] Allen, T. D., Golden, T. D., Shockley, K. M. (2015). How effective is telecommuting? Assessing the status of our scientific findings. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 16(2), pp. 40-68. <doi.org/10.1177/1529100615593273>.

[49] Chao, G. T. (1990). Exploration of the Conceptualization and Measurement of Career Plateau: A Comparative Analysis. Journal of Management. 16(1), pp. 69-80. <doi.org/10.1177/014920638801400107>.

[50] Feldman, D. C., Weitz, B. A. (1988). Career Plateaus Reconsidered. Journal of Management, 14(1), p. 69-80. <doi.org/10.1177/014920638801400107>.

[51] Milliman, J. F. (1992). Causes, Consequences, and Moderating Factors of Career Plateauing. Dissertation, University of Southern California.

[52] Parker, S. Morgeson F. (2017). One Hundred Years of Work Design Research: Looking Back and Looking Forward. Journal of Applied Psychology, 2017, Vol. 102, No. 3, pp. 403-420.

[53] Gajendran, R. S., Harrison, D. A. (2007). The Good, the Bad, and the Unknown About Telecommuting: Meta-Analysis of Psychological Mediators and Individual Consequences. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92(6), pp. 1524-1541. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92(6). <doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.92.6.1524>.

[54] Allen, T. D., Golden, T. D., Shockley, K. M. (2015). How effective is telecommuting? Assessing the status of our scientific findings. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 16(2), pp. 40–68. <doi.org/10.1177/1529100615593273>.

[55] Chao, G. T. (1990). Exploration of the Conceptualization and Measurement of Career Plateau: A Comparative Analysis. Journal of Management, 16(1), pp. 181-193. <doi.org/10.1177/014920638801400107>.

[56] Bakker, A. B., Demerouti, E. (2007). The Job Demands-Resources model: State of the art. In Journal of Managerial Psychology, Vol. 22, Issue 3, pp. 309-328. <doi.org/10.1108/02683940710733115>.

[57] Grant, A. M., Parker, S. K. (2009). 7 Redesigning Work Design Theories: The Rise of Relational and Proactive Perspectives. The Academy of Management Annals, 3(1), pp. 317-375.

[58] Wang, Y. H., Hu, C., Hurst, C. S., Yang, C. C. (2014). Antecedents and outcomes of career plateaus: The roles of mentoring others and proactive personality. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 85(3), pp. 319-328. <doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2014.08.003>.

Downloads

Downloads

Published

Issue

Section

License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.