Gendered Roles and Family Well-Being in Georgia: A Culturally Embedded Analysis for Intercultural Family Research

DOI:

https://doi.org/10.35945/gb.2025.20.008Keywords:

Intercultural family dynamics, gender and culture, cross-cultural psychology, post-Soviet cultural transformation, cultural values and parentingAbstract

This study explores the interplay between empathy, cooperative conflict resolution, and marital satisfaction within the framework of culturally embedded gender roles in Georgian families. Situated in the context of Georgia’s post-Soviet transformation, the research examines how traditional responsibilities assigned to mothers and fathers influence emotional dynamics and family well-being. Drawing from intercultural psychology, the study considers how cultural scripts, interdependence-oriented norms, and shifting gender expectations affect marital functioning across two life stages. Quantitative analysis reveals that women report higher empathy and collaborative conflict strategies, which correlate positively with marital satisfaction. Additionally, maternal perceptions of support significantly influence children’s well-being and fathers’ emotional engagement. These findings contribute to cross-cultural psychology by highlighting how family dynamics are shaped by cultural continuity and value shifts in transitional societies.

Keywords: Intercultural family dynamics, gender and culture, cross-cultural psychology, post-Soviet cultural transformation, cultural values and parenting.

Introduction

The well-being of a family is shaped not only by individual and interpersonal dynamics but also by the ontological structures that define gender roles within a given society. Traditional family structures, particularly in Georgia, have long assigned distinct responsibilities to husbands and wives, influencing marital satisfaction, conflict resolution, and parental engagement. However, these roles are not merely socially prescribed behaviors but also ontologically significant categories that shape individual identity and family dynamics.

Many factors influence family well-being, and their impact varies. For instance, parental conflict is crucial to understanding family dynamics, as it affects children’s development and family health.[1] Cummings, Taylor, and Merrilees (2020)[2] emphasize the importance of reducing interparental conflict to foster positive family dynamics. Effective communication, trust, and mutual support are essential for emotional stability.[3] Economic security also plays a role in family well-being by reducing stress and uncertainty,[4] with positive perceptions of financial stability improving family dynamics.[5] The association between family functioning and children’s emotional outcomes highlights the moderating role of parental mental health.[6] Child well-being often reflects family health and cohesion, including emotional, academic, and social aspects.[7] Marital satisfaction, influenced by communication, emotional support, empathy, conflict resolution, and financial stability, is another key determinant of family well-being.[8]

As we can see, family well-being is influenced by various factors, including parental conflict, social support networks, access to resources, community environments, and cultural norms. It is dynamic and can fluctuate based on life events, changes in relationships, and external stressors. Furthermore, the distribution of family roles, the effectiveness of family functioning, and the ability to cope with challenges are significant.[9] The nature of parental relationships is crucial; conflicts can severely deteriorate family well-being, while their absence fosters stability for both children and parents.[10]

Gender significantly influences family dynamics. Gottman and Levenson (1992)[11] found that wives are more emotional and defensive in marital conflicts, often initiating them, while husbands tend not to defuse situations. In successful marriages, women handle conflicts constructively, encouraging attentiveness from men. However, Zhu et al. (2022)[12] argue that these factors vary across cultures, highlighting the need for research in specific contexts like Georgia.

In Georgia, a post-Soviet country with unique social values, gender roles shape family dynamics. Women are typically the primary caregivers, responsible for emotional labor and child-rearing, while men are seen as financial providers.[13] Rising divorce rates reflect dissatisfaction with women’s roles, linked to post-Soviet changes that expanded economic opportunities for women. This shift has contributed to changing gender roles, reduced parental empathy, and family instability, particularly in middle age.[14]

While grounded in the Georgian cultural context, this study contributes to intercultural family psychology by examining how gendered roles function within a transitional society. Georgia’s post-Soviet transformation and evolving gender norms create a unique environment where traditional family expectations are renegotiated alongside modern influences. Compared to individualistic societies like Western Europe or North America, Georgian families often maintain hierarchical, role-specific structures rooted in collectivist traditions. This analysis complements cross-cultural studies, such as Kamo’s (1993)[15] comparison of marital satisfaction determinants in Japan and the United States, and Zhu et al. (2022)[16] findings on maternal emotional labor in China. By situating Georgia within this broader framework, the study highlights how gender roles, conflict resolution, and psychosocial support operate within culturally specific systems, offering transferable insights for understanding family functioning in transitional societies.

This study provides culturally embedded insight into gendered family dynamics in Georgia, offering comparative value for intercultural family psychology and extending findings from prior cross-cultural research (e.g., Kamo, 1993; Zhu et al., 2022).[17] It explores the interplay between empathy, cooperative conflict resolution, and marital satisfaction, particularly within the context of traditional and evolving gender roles in Georgia.

Understanding the differences in family dynamics across age categories and genders can inform targeted interventions and support strategies for couples at various life stages, ultimately improving family well-being and marital satisfaction.

Research Hypotheses:

Gender Differences in Empathy and Conflict Resolution.

- Women are more likely to exhibit higher levels of empathy and use cooperative strategies in marital conflict than men;

- Spouses who demonstrate higher empathy and utilize cooperative strategies in conflict are more satisfied with their marriages.

Influence of Maternal Psychosocial Support on Family Dynamics.

- A mother’s perception of psychosocial support affects her child’s perception of support. and well-being.

- A mother’s perception of psychosocial support affects the father’s perception of support, both her and her husband’s perception of their financial situation, and their marital functioning.

- A mother’s perception of psychosocial support positively correlates with the likelihood of marital conflict for both her and her husband.

1. Materials and Methods

The research consists of two phases, each examining family dynamics at different life stages in relation to gender roles, marital satisfaction, and family well-being. The first phase focuses on early-stage marriages, exploring how gender influences empathy and conflict resolution in the formative years. The second phase shifts to middle-aged parents with teenage children, investigating how perceptions of psychosocial support affect family well-being amid the challenges of adolescent development.

The first stage of this study utilized a probabilistic sampling method, and data were collected using Google Forms from April to May 2024. Respondents were informed about the anonymity of the research and that their responses would be used only in an aggregated form. Data were analyzed using IBM SPSS 20, employing univariate and multivariate analysis, independent samples t-tests, correlation analysis, and linear regression analysis.

A total of 150 early-age married respondents participated in the study, with 85 (56.7%) identifying as female and 65 (43.3%) as male. The majority (48%) were aged 18-24, while 55 (36.7%) were aged 25-34, and 23 (15.3%) were aged 35-44. There were used tools adapted in Georgian language. The Measurement tools were:

- Questionnaire Measure of Emotional Empathy (QMEE):[18] Developed by Albert Mehrabian and Norman Epstein in 1972, this questionnaire measures emotional empathy. It was adapted by Amiran Grigolava at the State Institute of Psychology of Uzbekistan. The QMEE consists of 33 statements, where respondents indicate their level of agreement based on their first reaction. Emotional empathy refers to the ability to share the feelings and experiences of others, distinct from cognitive empathy, which involves understanding another person’s perspective without sharing their emotions;

- Thomas-Kilmann Conflict Mode Instrument: Created by Kenneth Thomas and Ralph Kilmann in the early 1970s,[19] this tool assesses conflict management styles based on two dimensions: assertiveness and cooperation. It identifies five behavioral styles in conflict situations, consisting of 30 statements with two possible responses, from which respondents select the one that best describes their behavior. In the current study, instructions will specify that responses relate to conflicts in marriage;

- Norton Quality of Marriage Index: This established tool, developed by Susan Norton in 1983,[20] evaluates marital satisfaction and overall relationship quality. The questionnaire consists of six statements covering various relationship aspects, using a Likert scale from “strongly agree” to “strongly disagree”. It assesses dimensions such as communication, intimate relationships, conflict resolution, emotional support, and happiness in relationships. The results can help clinicians and researchers identify strengths and weaknesses in marital relationships.

On the second stage, to test our research hypotheses, in middle-aged spouses, we reanalyzed data from a study conducted in Spring 2023. The study involved 167 families in Georgia, with a total of 501 participants, including mothers, fathers, and their teenage children aged 11-18.

It covered various areas of family dynamics: Mother’s Feeling of Support, Mother’s Family Functioning, Mother’s Marital Conflict, Financial Well-being Perceived by Mother, Child’s Feeling of Well-being, Child’s Feeling of Support, Father’s Feeling of Support, Father’s Family Functioning, Financial Well-being Perceived by Father, and Father’s Marital Conflict. These scales were previously checked and found to be reliable and valid.

Participants completed a printed questionnaire. after providing informed consent to participate and share their answers for scientific studies. Participation was confidential and optional. Various recruitment methods were employed to ensure a fair and accessible process for all potential participants.

For the reanalysis using SPSS-21, mothers’ feelings of support were chosen as the independent variable, while other variables depended on it.

This study was conducted in strict accordance with ethical research guidelines. The authors adhered to the APA ethical principles, the Code of Conduct of the French Psychology Society, and the recommendations of COPE (Committee on Publication Ethics). Research involving human participants complied with the Declaration of Helsinki, ensuring voluntary participation, anonymity, and confidentiality. The first stage of data collection received informed consent from all participants, while the second-stage reanalysis was based on previously approved research. Where applicable, ethical approval was obtained from the appropriate committee, and no identifying information was disclosed.

Sample size was determined based on the availability of participants within the research context. No data were excluded from the analyses. No experimental manipulations were applied. All study measures administered are reported in this manuscript.

2. Results

2.1. Early marriage and gender roles in conflict and empathy

This stage highlighted whether gender-based expectations contribute to or hinder cooperative conflict resolution, which is particularly relevant in a cultural context like Georgia, where traditional gender roles are prevalent.

2.1.1. Marital satisfaction

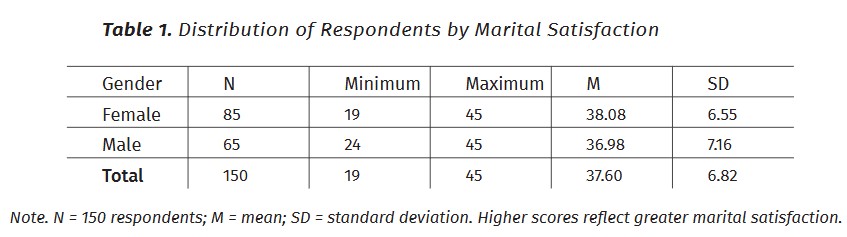

The study utilized the Norton Quality of Marriage Index, consisting of 6 statements rated on a 7-point Likert scale, to assess marital satisfaction. A higher score indicates greater marital satisfaction. The overall average score for the respondents was 37.6, with a standard deviation of 6.82. There was a slight difference in marital satisfaction scores based on gender, with female participants averaging 38.08 and male participants averaging 36.89. (Table 1).

2.1.2. Empathy

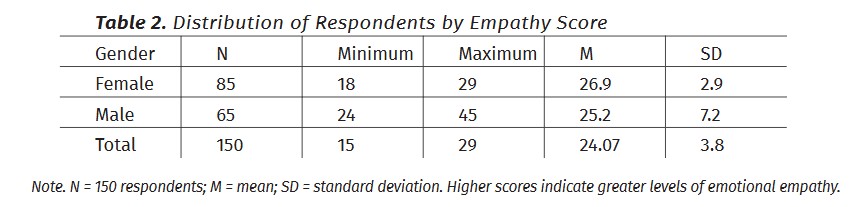

The average score for the respondents is 20.1, with females averaging 20.61 and males averaging 19.51. In this study, the average score for respondents was 24.07, with a standard deviation of 3.8. Female respondents had an average score of 26.9 (SD=2.9), while male respondents had an average score of 25.2 (SD=7.2) (Table 2). The results suggest that female respondents exhibit higher empathy levels compared to male respondents. This indicates a potential gender difference in emotional empathy, with females scoring higher on average. The overall average score of the sample population reflects a moderate level of empathy.

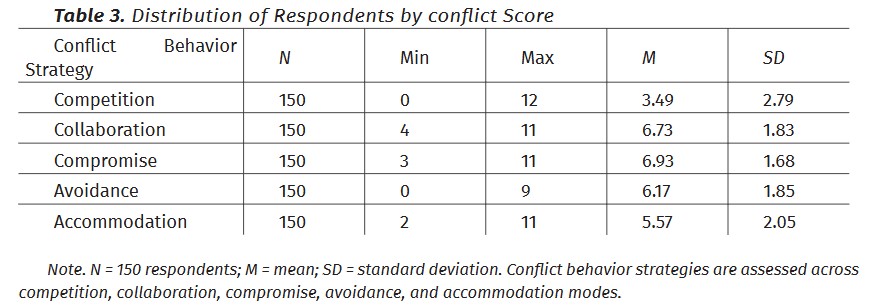

2.1.3. Conflict behavior strategies summary

The average empathy score for female respondents was significantly higher than that for male respondents (t(148) = 4.358, p < .01), supporting the study’s first hypothesis regarding gender differences in emotional empathy (Table 3). These findings suggest notable differences in conflict resolution strategies and empathy based on gender, indicating the potential need for tailored approaches in conflict management.

2.1.4. Gender differences in conflict behavior

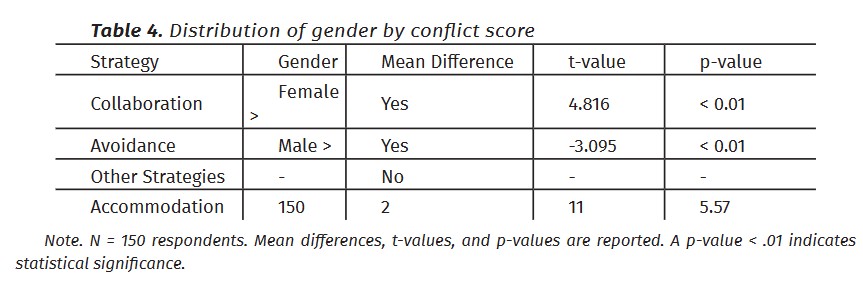

The study used an independent t-test to compare conflict behavior strategies between genders. Results indicated that:

Collaboration was significantly higher among females, with a mean difference significant at t=4.816, p<0.01t = 4.816, p < 0.01t=4.816, p<0.01;

Avoidance was more common among males, showing a significant difference at t=−3.095, p<0.01t = -3.095, p < 0.01t=−3.095, p<0.01; (Table 4)

No other strategies showed significant gender differences.

2.1.5. Correlations between marital satisfaction, empathy, and conflict strategies

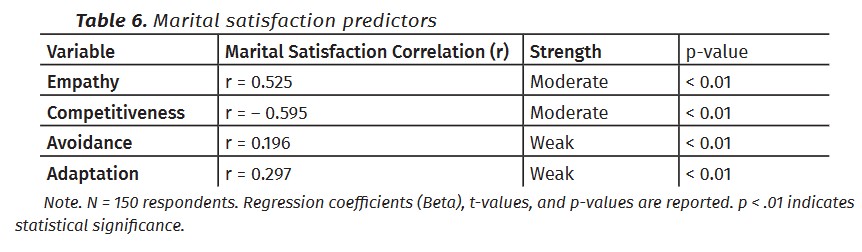

The study explored correlations between marital satisfaction, empathy, and conflict strategies using Pearson’s correlation (Table 5):

- Empathy showed a moderate positive correlation with marital satisfaction (r=.525, p<0.01r = .525, p < 0.01r=.525, p<0.01);

- Competitiveness correlated negatively with marital satisfaction (r=−0.595, p<0.01r = -0.595, p< 0.01r=−0.595, p<0.01);

- while Avoidance and Adaptation correlated positively but weakly.

2.1.6. Regression analysis for predictors of marital satisfaction

A regression analysis identified Empathy and Competitiveness as significant predictors of marital satisfaction, explaining 46% of its variability (R=0.46, p<0.01R = 0.46, p < 0.01R=0.46, p<0.01). (Table 6)

These results support the hypothesis that gender influences specific conflict behavior strategies and that empathy and certain strategies are linked to marital satisfaction.

2.2. Marital satisfaction in middle-aged parents with teenagers

The second phase of research has some steps, where the initial step in our analysis involved examining the relationships between the mother’s perception of psychosocial support and various family dynamics variables through correlation and regression analysis.

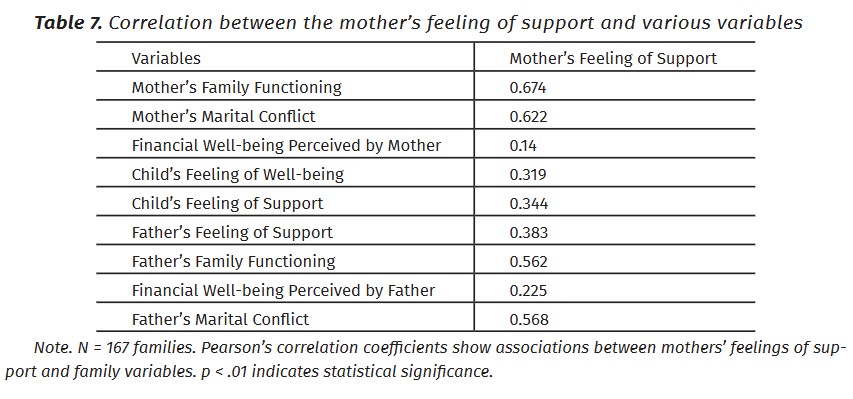

Correlation Analysis highlights several positive correlations between the mother’s feeling of support and various family dynamics variables (Table 7):

- There’s a significant positive correlation with: Family Functioning of both parents (r = .674, p< .01 & r = .562, p< .01); Marital conflict of both parents (r = .622, p< .01; r = .568, p< .01) and Father’s feeling of support (r = .383, p< .01);

- Weaker positive correlations are found between the mother’s feeling of support and financial well-being perceived father (r = .225, p< .01). Also, moderate positive correlations are observed with the child’s feeling of well-being (r = .319, p< .01) and perceived Support (r = .344, p< .01);

- Additionally, there is no statistically significant connection between the mother’s feeling of support and financial well-being perceived mother (r = .140, p > .05).

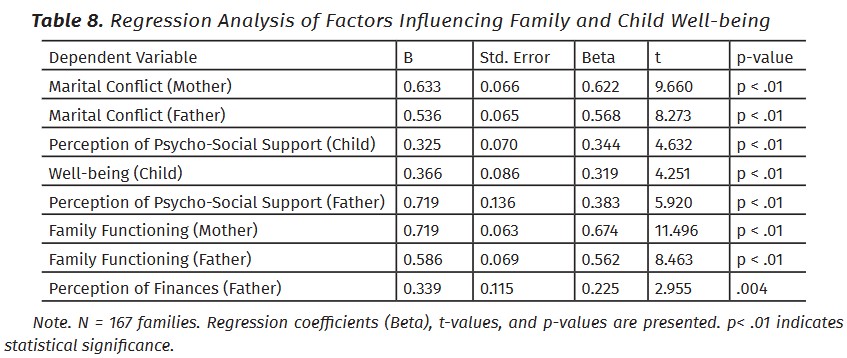

Regression Analysis indicates that the mother’s feeling of support is a significant predictor of various aspects of family dynamics, including marital conflict, psycho-social support, well-being of the child, and overall family functioning (Table 8):

- Strong predictive effects are observed when the feeling of support significantly influences the dependent variables. For instance, the feeling of support strongly predicts family functioning as perceived by the mother, with a Beta of 0.674 and a t-value of 11.496, and father with a Beta of 0.0.562 and a t-value of 8.463, indicating a robust relationship. Similarly, marital conflict as perceived by the mother also shows a strong predictive effect by the mother’s feeling, with a Beta of 0.622 and a t-value of 9.660, highlighting that changes in the feeling of support are closely related to changes in these dependent variables;

- The perception of psycho-social support of the mother has a moderate predictive effect on the father’s perception of psycho-social support, with a Beta of 0.383 and a t-value of 5.92. Similarly, the well-being of the child, with a Beta of 0.319 and a t-value of 4.251, and the child’s perception of psycho-social support of the child, with a Beta of 0.344 and a t-value of 4.632, indicate that the mother’s feeling of support moderately influences the child’s well-being.

Weak predictive effects are seen when the mother’s feeling of support has no significant influence on the dependent variables. An example of this is the perception of finances by the father, which shows a weak predictive effect with a Beta of 0.225 and a t-value of 2.955.

2.3. Summary

Research indicates significant gender differences in empathy and conflict resolution strategies, with women generally exhibiting higher levels of empathy than men. Findings show that female respondents score significantly higher on empathy measures compared to their male counterparts. Additionally, in marital conflicts, women tend to prefer cooperative strategies, such as collaboration, while men are more inclined to utilize neglectful approaches like avoidance. This aligns with the hypothesis that gender influences conflict resolution strategies, as the results confirm that spouses who demonstrate higher empathy and employ cooperative tactics tend to experience greater marital satisfaction, with positive correlations evident between these factors.

Furthermore, the influence of maternal psychosocial support on family dynamics plays a crucial role in shaping children’s well-being and parental relationships. A mother’s perception of support is positively correlated with her child’s well-being and influences the child’s perception of psychosocial support. Additionally, maternal support significantly impacts the father’s perception of support, indicating a shared dynamic within the family unit. While the correlation between maternal support and financial perception is weak, it still suggests a positive influence. Importantly, higher maternal psychosocial support is associated with reduced marital conflict and enhanced marital functioning for both parents, illustrating its vital role in fostering healthy family relationships and dynamics.

3. Findings and Discussion

Empirical data from early-stage and middle-aged marriages in Georgia illustrate the persistence of these gendered expectations. Women consistently report higher levels of empathy and cooperative conflict resolution strategies, aligning with social expectations of caregiving and emotional labor. However, the reliance on traditional gendered roles for emotional support often leads to asymmetrical dependencies, which can negatively impact marital satisfaction.[21] Also, reduces emotional connection and promotes unhealthier resolutions, leading to decreased marital satisfaction.[22]

In contrast, men’s preference for avoidance strategies can create barriers to effective communication and conflict resolution. This gendered approach may hinder relational satisfaction and contribute to unresolved issues, underscoring the necessity of encouraging men to engage in more empathetic and collaborative behaviors.[23]

Moreover, these gender dynamics in conflict resolution have broader implications for family functioning. As observed in the correlations presented in Table 7 and predictions in Table 8, maternal feelings of support significantly influence various aspects of family dynamics. A mother’s ability to foster an emotionally supportive environment can help mitigate the negative effects of men’s avoidance strategies, promoting healthier communication patterns and ultimately enhancing overall family well-being.

- Family Functioning: In Georgia, a mother’s perception of support strongly predicts family functioning as perceived by both parents. This connection reflects Georgian cultural norms where mothers often play a central role in nurturing family relationships and maintaining emotional stability. When mothers feel supported, they experience less relationship stress, leading to better communication, cooperation, and mutual support among couples. This supportive environment contributes to family cohesion and stability, which are essential for optimal child rearing and overall family well-being.[24]

- Marital Conflict: The feeling of support in Georgian mothers is a robust predictor of perceived marital conflict by both parents. Changes in the mother’s sense of support correlate closely with changes in marital conflict levels. In Georgian culture, which highly values familial harmony, a mother’s perception of support can contribute significantly to maintaining family stability. Feeling supported enables mothers to fulfill their roles effectively, thereby reducing tensions and enhancing marital satisfaction.[25]

- Father’s Perception of Psychosocial Support: The mother’s perception of psychosocial support moderately influences the father’s perception of support. This dependency in Georgia reflects cultural norms emphasizing familial interconnectedness and collective well-being. When mothers feel supported, they create a positive family atmosphere that influences how fathers perceive their own roles and support contributions within the family.[26]

- Child’s Well-being and Perception of Support: The mother’s feeling of support moderately influences the child’s well-being and their perception of support. This finding suggests that maternal support plays a crucial role in shaping children’s overall well-being. When mothers feel supported, they cultivate stable and nurturing environments that positively impact their children, thereby enhancing overall family welfare.[27]

- Financial Well-being Perceived by Father: Georgian mothers’ support perception has little effect on fathers’ financial views or their own, reflecting traditional norms where financial decisions are paternal domains. While evolving economic and social roles challenge caregiving expectations, gender and emotional labor remain deeply linked, indicating institutional change alone may not shift ingrained family dynamics.[28]

This study highlights how gendered expectations in Georgian families are both socially constructed and ontologically embedded. While empirical findings confirm links between empathy, conflict resolution, and marital satisfaction, deeper theoretical engagement reveals that these relationships are shaped by structural gender constraints. Though economic and social shifts challenge traditional roles, ingrained expectations around emotional labor persist.

Mothers play a crucial role in nurturing family relationships and maintaining emotional stability. When they feel supported, it enhances family cohesion, reduces stress, and fosters healthier marital and parental relationships. Addressing maternal perceptions of support can lead to interventions that enhance communication, cooperation, and mutual understanding between spouses, ultimately promoting marital satisfaction and stability. Stable and nurturing family environments created through maternal support positively impact children’s development and overall family dynamics.

The findings of this study contribute to intercultural psychology by illuminating how cultural scripts and value systems shape gendered roles and family functioning in a society undergoing sociocultural transition. In Georgia, the persistence of traditional maternal and paternal roles can be understood as a manifestation of cultural continuity following the Soviet era, where state-defined gender expectations—such as the glorification of maternal sacrifice and the emphasis on male economic provision—continue to influence contemporary family dynamics. From the perspective of acculturation theory, Georgian society reflects a partial integration of modern egalitarian ideals with deeply rooted collectivist norms. This dynamic interplay between post-Soviet tradition and emerging values creates role strain, particularly for women, who navigate conflicting expectations between caregiving and self-actualization. Additionally, the patterns observed in empathy and conflict resolution align with the cultural orientation toward interdependence,[29] which prioritizes harmony and obligation over individual assertiveness. By framing gendered family roles through the lens of acculturation, cultural scripts, and independence–interdependence theory, this study not only interprets Georgian-specific trends but also informs broader intercultural understanding of how cultural structures mediate psychological processes related to family life.

Conclusion

This study analyzed data from 150 early-stage married couples and 167 middle-aged families to examine the relationships between empathy, cooperative conflict resolution, maternal psychosocial support, and family dynamics. The findings provide varying levels of support for the hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1: Confirmed. Women are more likely to exhibit higher levels of empathy and use cooperative strategies in marital conflict than men.

Hypothesis 2: Supported. Spouses who demonstrate higher empathy and utilize cooperative strategies in conflict report higher levels of marital satisfaction.

Hypothesis 3: Supported. A mother’s perception of psychosocial support significantly influences her child’s perception of support and overall well-being.

Hypothesis 4: Supported. A mother’s perception of psychosocial support affects the father’s perception of support, as well as both parents’ perceptions of their financial situation and marital functioning.

Hypothesis 5: Supported. A mother’s perception of psychosocial support positively correlates with the likelihood of marital conflict for both her and her husband.

In conclusion, these findings emphasize that maternal perceptions of support are central to understanding both marital satisfaction and family dynamics, revealing the broader implications of shifting gender roles and expectations in contemporary Georgian families.

Limitations and further plans for research

The study’s limitations include using convenience sampling, limiting generalizability, and relying on self-reported data, which may be biased. The online survey format could exclude participants with limited internet access, and the focus on gender differences may overlook other factors like culture, socioeconomic status, or personality. Additionally, the study’s focus on early and middle-aged marriages in Georgia limits its broader applicability, and the cross-sectional design prevents establishing causality. Future research will expand the sample, use a longitudinal approach, and explore additional factors like personality and external stressors, possibly incorporating qualitative methods.

Competing Interests

The author(s) has/have no competing interests to declare.

References:

Chkeidze, M., Gudushauri, T. (2024). The Interplay of Tradition and Modernity: A Case Study of Gender Roles in Georgian Society. International Journal of Arts, Humanities and Social Sciences, 5(4). <doi.org/10.56734/ijahss.v5n4a3>;

Conger, R. D., Conger, K. J., Martin, M. J. (2010). Socioeconomic status, family processes, and individual development. Journal of Marriage and Family, 72(3). <https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2010.00725.x>;

Crouter, A. C., Booth, A. (2003). Children’s influence on family dynamics: The neglected side of family relationships. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers;

Cummings, E. M., Taylor, L. K., Merrilees, C. E. (2020). Evaluating parenting programs aimed at reducing interparental conflict: Implications for family well-being. Journal of Family Psychology, 34(3);

Don, B. P., Roubinov, D. S., Puterman, E., Epel, E. S. (2022). The role of interparental relationship variability in parent–child interactions: Results from a sample of mothers of children with autism spectrum disorder and mothers with neurotypical children. Journal of Marriage and Family, 84(5). <doi.org/10.1111/jomf.12852>;

Farrell, A. K., Simpson, J. A., Carlson, E. A., Englund, M. M., Sung, S. (2020). The impact of stress and support on family functioning: A longitudinal study. Journal of Family Psychology, 34(3);

Gaspar, T., Gomez-Baya, D., Trindade, J. S., Guedes, F. B., Cerqueira, A., de Matos, M. G. (2021). Relationship between family functioning, parents’ psychosocial factors, and children’s well-being. Journal of Family Issues, 0(0). <doi.org/10.1177/0192513X211030722>;

Gottman, J. M., Levenson, R. W. (1992). Marital processes predictive of later dissolution: Behavior, physiology, and health. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 63(2). <doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.63.2.221>;

Kamo, Y. (1993). Determinants of marital satisfaction: A comparison of the United States and Japan. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 10(4). <doi.org/10.1177/0265407593104005>;

Kitoshvili, N. (2023). Marital conflict and adolescent’s psycho-social well-being: Mediation and moderation analysis. Scientific Bulletin of Mukachevo State University. Series Pedagogy and Psychology, 9(4). <doi.org/10.52534/msu-pp4.2023.57>;

Leitão, C., Shumba, J. (2024). Promoting family wellbeing through parenting support in ECEC services: Parents’ views on a model implemented in Ireland. Frontiers in Education, 9, 1388487. <doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2024.1388487>;

Markus, H. R., Kitayama, S. (1991). Culture and the self: Implications for cognition, emotion, and motivation. Psychological Review, 98(2). <doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.98.2.224>;

Mastrotheodoros, S., Van der Graaff, J., Deković, M., Meeus, W. H. J., Branje, S. (2020). Parent-adolescent conflict across adolescence: Trajectories of informant discrepancies and associations with personality types. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 49(7). <doi.org/10.1007/s10964-019-01054-7>;

Mehrabian, A., Epstein, N. (1972). A measure of emotional empathy. Journal of Personality, 40(4). <doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.1972.tb00078.x>;

Meladze, G., Loladze, N. (2017). Population changes and characteristics of demographic processes in Tbilisi. Space - Society - Economy, 19. <doi.org/10.18778/1733-3180.19.05>;

Norton, R. (1983). Measuring marital quality: A critical look at the dependent variable. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 45(1). <doi.org/10.2307/351302>;

Shengelia, L. (2020). Maternal care in Georgia: An empirical analysis of quality, access and affordability during health care reform (Doctoral Thesis, Maastricht University). Maastricht University. <doi.org/10.26481/dis.20200319ls>;

Taylor, Z. E., Conger, R. D. (2017). Promoting strengths and resilience in single-mother families. Child Development Perspectives, 11(2). <doi.org/10.1111/cdev.12741>;

Teuber, Z., Sielemann, L., Wild, E. (2022). Facing academic problems: Longitudinal relations between parental involvement and student academic achievement from a self-determination perspective. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 90(4). <doi.org/10.1111/bjep.12551>;

Thomas, K. W., Kilmann, R. H. (1974). Thomas-Kilmann Conflict Mode Instrument (TKI) [Database record]. APA PsycTests. <doi.org/10.1037/t02326-000>;

Uchino, B. N. (2004). Social Support and Physical Health: Understanding the Health Consequences of Relationships. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. <dx.doi.org/10.12987/yale/9780300102185.001.0001>;

UNDP. (2019). Men, women, and gender relations in Georgia: Public perceptions and attitudes. United Nations Development Programme. <https://www.undp.org/georgia/publications/men-women-and-gender-relations-georgia-public-perceptions-and-attitudes>;

Varughese, B., Jayan, C., AV, G. (2023). Conflict styles & relationship satisfaction. International Journal of Science, Engineering and Management, 10(11), p. 38. <https://www.ijsem.org>;

Walsh, F. (2016). Strengthening family resilience. New York, NY: Guilford Press;

Zhu, J., Liu, M., Shu, X., Xiang, S., Jiang, Y., Li, Y. (2022). The moderating effect of marital conflict on the relationship between social avoidance and socio-emotional functioning among young children in suburban China. Developmental Psychology, 13, article number 1009528. <doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.1009528>.

Footnotes

[1] Don, B. P., Roubinov, D. S., Puterman, E., Epel, E. S. (2022). The role of interparental relationship variability in parent–child interactions: Results from a sample of mothers of children with autism spectrum disorder and mothers with neurotypical children. Journal of Marriage and Family, 84(5), pp. 1109-1126. <doi.org/10.1111/jomf.12852>.

[2] Cummings, E. M., Taylor, L. K., Merrilees, C. E. (2020). Evaluating parenting programs aimed at reducing interparental conflict: Implications for family well-being. Journal of Family Psychology, 34(3), pp. 297-307.

[3] Crouter, A. C., Booth, A. (2003). Children’s influence on family dynamics: The neglected side of family relationships. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers.

[4] Conger, R. D., Conger, K. J., Martin, M. J. (2010). Socioeconomic status, family processes, and individual development. Journal of Marriage and Family, 72(3), pp. 685-704. <https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2010.00725.x>.

[5] Taylor, Z. E., Conger, R. D. (2017). Promoting strengths and resilience in single-mother families. Child Development Perspectives, 11(2), pp. 87-92. <doi.org/10.1111/cdev.12741>; Walsh, F. (2016). Strengthening family resilience. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

[6] Mastrotheodoros, S., Van der Graaff, J., Deković, M., Meeus, W. H. J., Branje, S. (2020). Parent-adolescent conflict across adolescence: Trajectories of informant discrepancies and associations with personality types. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 49(7), pp. 1587-1601. <doi.org/10.1007/s10964-019-01054-7>.

[7] Farrell, A. K., Simpson, J. A., Carlson, E. A., Englund, M. M., Sung, S. (2020). The impact of stress and support on family functioning: A longitudinal study. Journal of Family Psychology, 34(3), pp. 319-329; Teuber, Z., Sielemann, L., Wild, E. (2022). Facing academic problems: Longitudinal relations between parental involvement and student academic achievement from a self-determination perspective. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 90(4), pp. 876-894. <doi.org/10.1111/bjep.12551>.

[8] Kamo, Y. (1993). Determinants of marital satisfaction: A comparison of the United States and Japan. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 10(4), pp. 505-520. <doi.org/10.1177/0265407593104005>.

[9] Uchino, B. N. (2004). Social Support and Physical Health: Understanding the Health Consequences of Relationships. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. <dx.doi.org/10.12987/yale/9780300102185.001.0001>.

[10] Don, B. P., Roubinov, D. S., Puterman, E., Epel, E. S. (2022). The role of interparental relationship variability in parent–child interactions: Results from a sample of mothers of children with autism spectrum disorder and mothers with neurotypical children. Journal of Marriage and Family, 84(5), pp. 1109-1126. <doi.org/10.1111/jomf.12852>.

[11] Gottman, J. M., Levenson, R. W. (1992). Marital processes predictive of later dissolution: Behavior, physiology, and health. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 63(2), pp. 221-230. <doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.63.2.221>.

[12] Zhu, J., Liu, M., Shu, X., Xiang, S., Jiang, Y., Li, Y. (2022). The moderating effect of marital conflict on the relationship between social avoidance and socio-emotional functioning among young children in suburban China. Developmental Psychology, 13, article number 1009528. <doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.1009528>.

[13] Shengelia, L. (2020). Maternal care in Georgia: An empirical analysis of quality, access and affordability during health care reform (Doctoral Thesis, Maastricht University). Maastricht University. <doi.org/10.26481/dis.20200319ls>.

[14] Meladze, G., Loladze, N. (2017). Population changes and characteristics of demographic processes in Tbilisi. Space - Society - Economy, 19, pp. 87-103. <doi.org/10.18778/1733-3180.19.05>.

[15] Kamo, Y. (1993). Determinants of marital satisfaction: A comparison of the United States and Japan. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 10(4), pp. 505-520. <https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407593104005>.

[16] Zhu, J., Liu, M., Shu, X., Xiang, S., Jiang, Y., Li, Y. (2022). The moderating effect of marital conflict on the relationship between social avoidance and socio-emotional functioning among young children in suburban China. Developmental Psychology, 13, article number 1009528. <doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.1009528>.

[17] Ibid.

[18] Mehrabian, A., Epstein, N. (1972). A measure of emotional empathy. Journal of Personality, 40(4), pp. 525-543. <doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.1972.tb00078.x>.

[19] Thomas, K. W., Kilmann, R. H. (1974). Thomas-Kilmann Conflict Mode Instrument (TKI) [Database record]. APA PsycTests. <doi.org/10.1037/t02326-000>.

[20] Norton, R. (1983). Measuring marital quality: A critical look at the dependent variable. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 45(1), pp. 141–151. <doi.org/10.2307/351302>.

[21] Chkeidze, M., Gudushauri, T. (2024). The Interplay of Tradition and Modernity: A Case Study of Gender Roles in Georgian Society. International Journal of Arts, Humanities and Social Sciences, 5(4), pp. 1-10. <doi.org/10.56734/ijahss.v5n4a3>.

[22] Gottman, J. M., Levenson, R. W. (1992). Marital processes predictive of later dissolution: Behavior, physiology, and health. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 63(2), pp. 221-230. <doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.63.2.221>.

[23] Varughese, B., Jayan, C., AV, G. (2023). Conflict styles & relationship satisfaction. International Journal of Science, Engineering and Management, 10(11), p. 38. <https://www.ijsem.org>.

[24] Taylor, Z. E., Conger, R. D. (2017). Promoting strengths and resilience in single-mother families. Child Development Perspectives, 11(2), pp. 87-92. <doi.org/10.1111/cdev.12741>.

[25] Kitoshvili, N. (2023). Marital conflict and adolescent’s psycho-social well-being: Mediation and moderation analysis. Scientific Bulletin of Mukachevo State University. Series Pedagogy and Psychology, 9(4), pp. 57-64. <doi.org/10.52534/msu-pp4.2023.57>.

[26] Gaspar, T., Gomez-Baya, D., Trindade, J. S., Guedes, F. B., Cerqueira, A., de Matos, M. G. (2021). Relationship between family functioning, parents’ psychosocial factors, and children’s well-being. Journal of Family Issues, 0(0), pp. 1-18. <doi.org/10.1177/0192513X211030722>.

[27] Leitão, C., Shumba, J. (2024). Promoting family wellbeing through parenting support in ECEC services: Parents’ views on a model implemented in Ireland. Frontiers in Education, 9, 1388487. <doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2024.1388487>.

[28] UNDP. (2019). Men, women, and gender relations in Georgia: Public perceptions and attitudes. United Nations Development Programme. Available at: <https://www.undp.org/georgia/publications/men-women-and-gender-relations-georgia-public-perceptions-and-attitudes>.

[29] Markus, H. R., Kitayama, S. (1991). Culture and the self: Implications for cognition, emotion, and motivation. Psychological Review, 98(2), pp. 224-253. <doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.98.2.224>.

Downloads

Downloads

Published

Issue

Section

License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.