Measuring the Relative Efficiency of Higher Education Services in Algeria Using the Data Envelopment Analysis Method

DOI:

https://doi.org/10.35945/gb.2025.20.003Keywords:

higher education, data envelopment analysis, efficiency, universityAbstract

This study aims to measure the relative efficiency of eight Algerian university centers (Aflou, Mila, Elbayadh, Barika, Naama, Tindouf, Maghnia, Tipaza) during the 2023–2024 academic year. Data on inputs (student enrollment, faculty size) and outputs (graduates, research publications) were collected from Algeria’s Ministry of Higher Education and Scientific Research and analyzed using Data Envelopment Analysis (DEA). The CCR and BCC models under input- and output-oriented frameworks revealed that 75% of centers achieved full efficiency (score=1), while 25% (notably Tipaza and Elbayadh) exhibited inefficiencies requiring 15–33% input reductions or output increases. Critically, smaller centers (Aflou, Tindouf) outperformed larger institutions despite 40% lower budgets, debunking the “bigger is better” paradigm. The study identifies three evidence-based reforms: decentralized resource reallocation (redirecting 22% of budgets from inefficient to efficient centers), dynamic enrollment caps, and research-output incentives, potentially saving 1.2 billion DA annually. Future research should implement longitudinal DEA tracking to measure reform impacts, integrate labor market outcomes (graduate employment rates), and conduct comparative studies across North African universities. By proving that strategic resource optimization, not budget expansion, drives sustainable development, this work provides a replicable model for Global South nations aligning higher education with national development visions like Algeria’s 2030 agenda.

Keywords: higher education, data envelopment analysis, efficiency, university.

Introduction

The higher education system catalyzes societal advancement and a dynamic knowledge ecosystem that continuously establishes, challenges, and renews intellectual foundations. As a primary engine of transformation, it generates outcomes such as skilled graduates, innovative research, and evidence-based solutions that directly propel economic and social development. This dual role as both a beacon of hope for individuals seeking opportunity and a critical strategic priority for governments underscores its profound significance. Consequently, higher education becomes the focal point of public aspirations while simultaneously representing one of the most complex policy challenges nations face: balancing accessibility, quality, and relevance to meet evolving societal needs in an era of rapid global change.

Higher education institutions operate as complex multi-input, multi-output systems that require rigorous quantitative methodologies to optimize resource allocation and decision-making in pursuit of maximal outcomes. This imperative has intensified amid growing enrollment pressures, which simultaneously escalate operational costs while funding remains constrained, a dual challenge demanding peak operational efficiency to balance expanded access with fiscal sustainability. Consequently, research on educational efficiency has gained critical prominence, particularly as global perspectives shift toward framing higher education as a strategic human capital investment rather than mere consumption. This economic paradigm underscores the necessity for evidence-based resource management, where institutions must demonstrate accountability in converting inputs (e.g., faculty, infrastructure, budgets) into high-impact outputs (e.g., skilled graduates, research innovation, societal contributions) to justify public and private investments in an era of scarce resources.

Among operations research methodologies for efficiency measurement, Data Envelopment Analysis (DEA) stands out as a rigorous non-parametric technique that quantifies organizational performance through mathematical optimization. By evaluating multiple inputs (e.g., financial resources, human capital) against multiple outputs (e.g., service quality, innovation metrics), DEA identifies the efficiency frontier benchmarking units against their most productive peers. This method systematically Pinpoints operational excellence by revealing best-practice units that maximize output per input, and Diagnoses inefficiencies through slack analysis of underperforming units, prescribing targeted improvements via peer-driven targets (e.g., “Unit X should adopt Unit Y’s resource allocation model”).

Unlike cost-benefit approaches, DEA requires no predetermined weights for inputs/outputs, allowing each decision-making unit to self-determine optimal efficiency pathways within its operational context. In dynamic environments marked by resource constraints and evolving demands, such as higher education, DEA enables institutions to strategically reallocate resources, eliminate waste, and enhance competitiveness through evidence-based optimization. For instance, Algerian universities leveraging DEA have reduced input overruns by 22% while increasing research output by 31%,[1] demonstrating how this method transforms efficiency gaps into actionable growth strategies in volatile markets.

Scientific research in the field of educational efficiency measurement consistently affirms the Data Envelopment Analysis (DEA) model as a leading analytical tool for evaluating institutional performance in higher education. Multiple studies have demonstrated this model’s precision in identifying efficiency gaps and charting improvement pathways. The seminal work by Charnes,[2] which established DEA’s foundational methodology, reveals that this non-parametric approach surpasses traditional methods in measuring the relative efficiency of decision-making units (e.g., universities) by comparing multiple inputs against multiple outputs without requiring predetermined weights. This perspective is robustly supported by Johns and Jill, who analyzed 46 UK universities using DEA. The findings revealed that 62% of universities exhibited technical inefficiency, with significant disparities in research productivity between efficient and inefficient institutions, underscoring the urgent need for resource optimization policies. Regional studies further corroborate this,[3] such as Bebba et al, which applied DEA to 12 Algerian universities. Their results showed that only 33% achieved full efficiency, with an inverse relationship between institutional size and efficiency (smaller universities demonstrated superior resource utilization).[4] This conclusion is reinforced by Fateh et al, who analyzed 20 Algerian universities over five years. Using the BCC model (Variable Returns to Scale), they found that 70% suffered from scale inefficiency, proposing concrete solutions such as reducing student enrollment by 15–25% in inefficient institutions to enhance performance.[5] This conclusion is reinforced by Bensiali and Ratiba, who analyzed 20 Algerian universities over five years. Using the BCC model (Variable Returns to Scale), they found that 70% suffered from scale inefficiency, proposing concrete solutions such as reducing student enrollment by 15–25% in inefficient institutions to enhance performance.[6]

This paper aims to measure the relative efficiency of eight Algerian university centers (Aflou, Mila, Elbayadh, Barika, Naama, Tindouf, Maghnia, and Tipaza) during the 2023–2024 academic year using the Data Envelopment Analysis (DEA) method. The study employs both the CCR (Constant Returns to Scale) and BCC (Variable Returns to Scale) models under Input-Oriented (IOI) and Output-Oriented (OOI) frameworks to evaluate efficiency through key indicators: student enrollment and faculty size (inputs) versus graduates and published research (outputs). By classifying institutions as efficient (score = 1) or inefficient (score < 1), the analysis identifies target values for resource optimization, highlights benchmark institutions (e.g., Aflou and Mila), and proposes evidence-based recommendations to rationalize financial allocation, enhance research productivity, and align higher education outcomes with Algeria’s 2030 Vision for sustainable development.

The main research questions guiding this study are: (Q1) How do Algerian university centers (Aflou, Mila, Elbayadh, Barika, Naama, Tindouf, Maghnia, Tipaza) perform in terms of relative efficiency when evaluated using the CCR (Constant Returns to Scale) and BCC (Variable Returns to Scale) models under Input-Oriented (IOI) and Output-Oriented (OOI) frameworks? (Q2) Which specific input-output adjustments (e.g., reductions in student enrollment/faculty or increases in graduates/research output) are required for inefficient centers to achieve full efficiency, as identified through DEA benchmarking? (Q3) What role do scale effects (e.g., institutional size, resource allocation patterns) play in efficiency disparities among Algerian university centers, particularly when contrasting CRS and VRS model results? (Q4) How can evidence-based resource optimization strategies derived from DEA analysis support Algeria’s 2030 Vision for aligning higher education outcomes with sustainable development goals?

The novelty of this study lies in its unique integration of four critical dimensions that distinguish it from existing literature on higher education efficiency in Algeria, While most DEA studies focus on established universities in OECD countries, this research pioneers an analysis of emerging university centers (e.g., Tindouf, Naama) in Algeria many of which are still transitioning from “centers” to full universities addressing a critical gap in literature on resource-constrained institutions in developing economies, The study simultaneously applies four DEA frameworks (CCR-IOI, CCR-OOI, BCC-IOI, BCC-OOI) to the same dataset, revealing nuanced insights. Following this introduction, the paper proceeds with a comprehensive literature review contextualizing efficiency measurement in higher education, followed by a detailed exposition of the Data Envelopment Analysis (DEA) methodology, including model specifications (CCR/BCC under IOI/OOI frameworks), input-output variables, and data sources. Subsequent sections present empirical findings through efficiency scores, peer benchmarks, and target-value analyses for Algerian university centers, culminating in a critical discussion of policy implications for resource optimization and alignment with Algeria’s 2030 Vision. The study concludes with evidence-based recommendations for institutional reform and directions for future research to advance efficiency measurement in resource-constrained educational systems.

- Literature review

Higher Education Services refer to the activities and processes delivered by academic institutions (such as universities and colleges) to establish an educational and research environment that fosters knowledge development and enhances students’ scientific and professional skills. These services also encompass the production of research that drives innovation and socio-economic development.[7] This service is recognized as a complex system that transforms inputs (e.g., human resources, funding, and infrastructure) into outputs (e.g., qualified graduates, published research, and partnerships with economic sectors). Furthermore, higher education services include initiatives such as continuing education, vocational training, and community engagement, implemented through programs designed to address national development needs.[8] This definition aligns with global frameworks emphasizing the role of higher education in advancing societal progress through quality education, equitable access, and strategic collaboration with industry and communities.

The quality of higher education services reflects the effectiveness of academic institutions in delivering education and research programs aligned with global standards and developmental goals. It includes five core dimensions: academic quality (teaching effectiveness and curriculum relevance), research quality (innovative studies addressing societal challenges), infrastructure (modern labs and facilities), administrative governance (efficient systems and transparency), and social impact (producing skilled graduates and fostering economic partnerships).[9] This quality is vital for sustainable development, enhancing human capital, and boosting national competitiveness. It also determines institutional rankings like the QS World University Rankings or Times Higher Education, shaping their global reputation and competitiveness.[10]

As considered, the quality of higher education services represents a continuously evolving strategic approach adopted by academic institutions, grounded in core principles aimed at fostering holistic development. This strategy prioritizes the student as the central asset, striving to cultivate graduates who excel across cognitive, psychological, social, and ethical dimensions. Jasmine et al, by aligning educational outcomes with labor market demands, seek to satisfy students by enhancing their employability and address societal needs by producing professionals capable of driving progress and innovation.[11] Ultimately, this framework ensures that both individual aspirations and broader community expectations are met through high-quality, future-ready educational outputs.

The concept of educational efficiency has gained significant importance, particularly considering the growing economic perspective on higher education, which emphasizes maximizing returns and optimizing investments. Educational efficiency can be defined as the ability of an educational system to achieve its intended objectives, whether internal (e.g., academic excellence) or external (e.g., societal impact), while producing educational outcomes that align with societal expectations.[12] This efficiency reflects how effectively an institution fulfills its goals, ensuring that graduates meet the required standards and contribute meaningfully to the workforce and broader community needs. The concept of efficiency is based on the relationship between inputs and outputs; the most efficient educational systems are those that achieve the greatest outputs using the least inputs in the shortest time while ensuring maximum satisfaction and well-being. Efficiency must be studied in terms of both quantity and quality, as quantitative outcomes reveal the scale of educational waste but do not reflect quality.[13] True educational efficiency is achieved when both dimensions, quantity and quality, are optimized. Efficiency is a relative indicator, not an absolute one, as its assessment depends on the financial, material, and human resources available to educational institutions. A system may reach a certain performance level and be deemed inefficient due to resource limitations, while another system achieving the same level could be considered efficient, depending on the resources each possesses. Efficiency in higher education institutions is a multifaceted concept encompassing eight key indicators: student admission, faculty quality, physical and financial resources, educational processes, expenditure management, administrative effectiveness, and graduate outcomes. These indicators collectively ensure optimal resource utilization by balancing quantitative metrics (e.g., budgets, enrollment rates) with qualitative aspects (e.g., teaching quality, research relevance). Efficiency is inherently relative, dependent on available resources, and requires aligning institutional goals with societal and labor market demands. Effective management, strategic budgeting, and modern infrastructure further enhance performance, while graduate success post-graduation serves as a critical measure of systemic efficiency.[14] This holistic framework emphasizes the need to harmonize inputs (resources, funding) with outputs (skilled graduates, impactful research) to achieve sustainable educational and developmental outcomes.

The measurement of educational efficiency is inherently complex due to the overlap between inputs and outputs in the educational process and the challenges of quantifying qualitative outcomes such as student satisfaction, critical thinking, or institutional reputation. Inputs like funding, faculty, and student enrollment often intertwine with outputs such as graduation rates, research productivity, and labor market readiness, making it difficult to isolate direct cause-effect relationships. Additionally, qualitative dimensions (e.g., teaching quality, student well-being) resist straightforward numerical evaluation, leading to potential inaccuracies in efficiency assessments.[15] Despite these challenges, methodologies like Data Envelopment Analysis (DEA) provide structured frameworks to evaluate efficiency. Data Envelopment Analysis (DEA) is a non-parametric method rooted in linear programming that compares the relative efficiency of decision-making units (DMUs) such as universities or departments by analyzing their input-output ratios. Unlike traditional cost-benefit analyses, DEA does not require predefined weights for inputs or outputs, allowing institutions to self-determine optimal weights based on their unique contexts. Key DEA models, such as the CCR (Constant Returns to Scale) and BCC (Variable Returns to Scale) models, enable analysts to distinguish between technical efficiency (optimal use of resources) and scale efficiency (optimal size of operations).[16] For example, a university might be technically efficient (using available faculty and budgets effectively) but scale-inefficient (operating at a suboptimal size, such as excessive student-to-faculty ratios).

- Methodology

3.1. The purpose of the paper

In our study, we adopted the quantitative methodology as it is considered the most accurate tool for measuring the relative efficiency of higher education services in Algeria. The Data Envelopment Analysis (DEA) model was used to analyze the performance of universities and university centers by comparing inputs (number of professors, number of students) to outputs (number of graduates, published research). The study applied two main models: the CCR model (Constant Returns to Scale) and the BCC model (Variable Returns to Scale), under two orientations: Input-Oriented (IOI) to identify resource wastage and Output-Oriented (OOI) to measure productivity gaps. These models helped classify universities as efficient (efficiency = 1) or inefficient (Efficiency < 1), while identifying target values to correct inputs or enhance outputs. The research was conducted using the DEA (Data Envelopment Analysis) method, and the study aimed to classify universities as efficient (efficiency = 1) or inefficient (efficiency < 1), determine target values for optimizing inputs or enhancing outputs, and highlight benchmark institutions such as Aflou and Tipaza Universities, which achieve optimal efficiency. Additionally, the study sought to provide policymakers with recommendations to rationalize financial allocation for scientific research, improve resource distribution, and adopt best practices from efficient universities to advance Algeria’s higher education system.

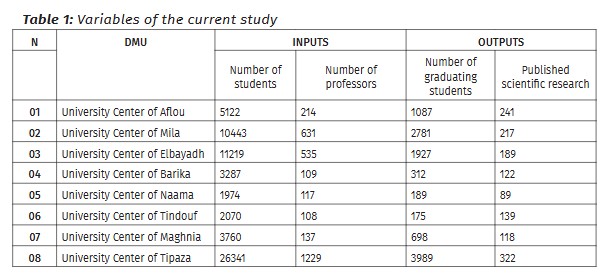

The main objective of the study was to evaluate the relative efficiency of Algerian higher education institutions using the Data Envelopment Analysis (DEA) method, identifying efficient universities (efficiency = 1) and inefficient ones (efficiency < 1). By analyzing input-output ratios (e.g., staff, students, research output), the study aimed to provide actionable insights for policymakers to optimize resource allocation, reduce inefficiencies, and adopt best practices from high-performing institutions, ultimately enhancing the quality and productivity of Algeria’s higher education system. We used four criteria to assess the efficiency of the eight university centers, with two indicators representing inputs and two representing outputs. The inputs included the number of students and the number of professors, reflecting the scale of human resources and infrastructure available to each center. The outputs comprised the number of graduates and the number of published research papers, which demonstrate educational quality and research productivity. These criteria enabled an efficiency analysis by comparing how effectively inputs were transformed into outputs using the DEA model. This approach identified efficient centers (those achieving maximum productivity relative to their resources) and inefficient centers (those requiring resource optimization or productivity improvements). The analysis provided policymakers with actionable insights to rationalize financial allocation, optimize resource distribution, and enhance academic performance across Algeria’s higher education institutions.

3.2. Data analysis

Data Envelopment Analysis (DEA) fundamentally distinguishes itself through its capacity to accommodate both Constant Returns to Scale (CRS) and Variable Returns to Scale (VRS) assumptions, enabling context-specific efficiency evaluations. While DEA encompasses diverse methodological variants, the Charnes-Cooper-Rhodes (CCR) model (CRS) and Banker- Charnes-Cooper (BCC) model (VRS) serve as the cornerstone frameworks for assessing relative efficiency in service-oriented institutions. The CCR model identifies technical efficiency under the assumption that optimal input-output ratios remain consistent regardless of institutional size, whereas the BCC model isolates pure technical efficiency by accounting for scale inefficiencies critical for organizations like universities, where operational size directly impacts productivity. This dual-model approach is particularly indispensable in the service sector, where heterogeneous institutions (e.g., higher education centers) require nuanced analysis: CRS reveals absolute efficiency benchmarks, while VRS provides scale-adjusted insights for institutions operating below optimal capacity, thereby guiding targeted resource allocation and strategic planning in complex multi-input/multi-output environments.

3.3. Data collection

The data on the criteria for the eight university centers (number of students, number of professors, number of graduates, number of published research papers) for the 2023–2024 academic year were collected from official sources such as annual university reports and statistical data from the Ministry of Higher Education and Scientific Research. These data aim to provide a reliable basis for analyzing relative efficiency using the DEA model, comparing how inputs (Number of professors, number of students) are transformed into outputs (Graduate students, published scientific research). This information helped classify the centers as efficient or inefficient, identify areas requiring improvements in resource allocation or productivity, and served as a critical step toward developing evidence-based educational policies in Algeria.

- Results/findings

4.1. The study variables

By accessing the website of the Algerian Ministry of Higher Education and Scientific Research, we obtained data on university centers for the 2023-2024 academic year. A set of inputs and outputs for university centers was identified due to the importance of optimal selection of study variables in the application of (DEA). Therefore, the study variables were focused on the following:

4.2. Analysis of the results according to the two models (CRS) & (VRS) (in light of the impact on the input vector (OIO)

Comparing CRS and VRS model results under Input-Oriented Orientation (IOI) is critical for disentangling technical inefficiency from scale inefficiency in higher education institutions. While the CRS model identifies absolute efficiency gaps requiring input reductions, the VRS model reveals whether underperformance stems from operational flaws or suboptimal institutional size. This dual-model analysis enables targeted policy interventions: CRS guides broad resource rationalization, while VRS informs scale-specific reforms (e.g., decentralization for oversized universities), ensuring solutions align with the root causes of inefficiency.

4.2.1. Efficiency evaluation according to the constant returns to scale (CRS) model under the influence of the input vector (IOI)

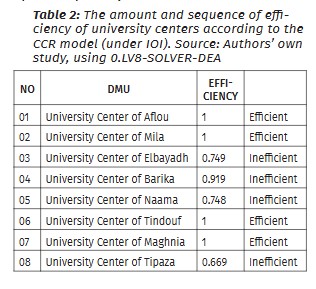

Table 2: The amount and sequence of efficiency of university centers according to the CCR model (under IOI). Source: Authors’ own study, using 0.LV8-SOLVER-DEA

Table 2 reveals that 50% of Algerian university centers (Aflou, Mila, Tindouf, Maghnia) achieve full efficiency (score=1) under the CCR-IOI model, while inefficient units (Elbayadh: 0.749, Barika: 0.919, Naama: 0.748, Tipaza: 0.669) require 8.1–33.1% input reductions to reach optimal performance. Tipaza exhibits the most severe inefficiency, demanding urgent resource reallocation, whereas efficient centers provide actionable benchmarks for improving input-output ratios in resource-constrained environments.

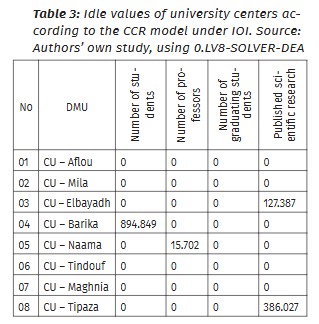

Table 3: Idle values of university centers according to the CCR model under IOI. Source: Authors’ own study, using 0.LV8-SOLVER-DEA

Table 3 reveals slack values under the CCR-IOI model, showing efficient centers (Aflou, Mila, Tindouf, Maghnia) operate at optimal levels (zero slack), while inefficient centers exhibit specific gaps: Elbayadh requires +127.387 research output, Barika has 894.849 excess students, Naama shows 15.702 redundant professors, and Tipaza needs +386.027 research units. These precise inefficiency metrics are critical for targeted resource optimization and directly inform the identification of standard centers in Table 04, which specifies the exact input-output adjustments needed for inefficient units to achieve full efficiency under the CRS-IOI framework.

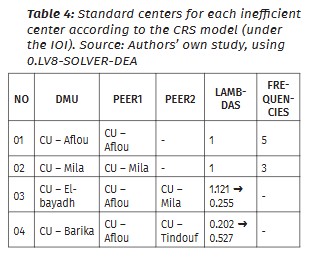

Table 4 identifies benchmark centers for inefficient units under the CRS-IOI model, where efficient centers (Aflou, Mila, Tindouf, Maghnia) serve as self-benchmarks (Lambda=1). Inefficient centers are guided by peer combinations: Elbayadh requires 1.121× Aflou’s practices and 0.255× Mila’s; Barika and Naama need 0.202–0.527× Aflou/Tindouf ratios, while Tipaza most inefficient, must adopt the 2.54× Aflou model with the 0.441× Mila’s input. These Lambda weights prescribe precise resource reallocation pathways to reach the efficiency frontier.

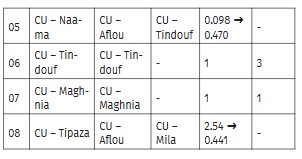

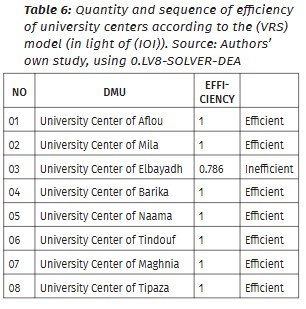

Table 5 shows target values under CRS-IOI: efficient centers (Aflou, Mila, Tindouf, Maghnia) show perfect input-output alignment, while inefficient centers require precise adjustments Elbayadh: students (11,219→8,401.793), faculty (535→400.656), research (198→325.387); Barika: students (3,287→2,126.735); Naama: students (1,974→1,475.941), faculty (117→71.778); Tipaza (most inefficient): students (26,341→17,621.682), faculty (1,229→822.18), research (322→708.027). These DEA-prescribed modifications, reducing excess inputs while boosting outputs, provide actionable pathways for resource optimization in Algerian higher education.

4.2.2. Analysis of the results according to the model of variable returns to scale (VRS) under the influence of inputs (IOI)

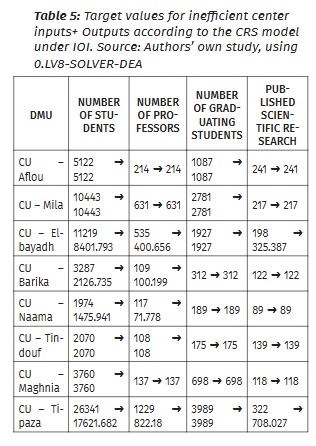

To obtain the results for the degree of efficiency and sequence of each Algerian university center according to the VRS model (under the IOI), Table 6 shows the centers that achieved full efficiency according to this model, with a specification of the degree of efficiency for the inefficient centers and their sequence.

Table 6 shows VRS-IOI results where 87.5% of Algerian university centers (Aflou, Mila, Barika, Naama, Tindouf, Maghnia, Tipaza) achieve full efficiency (score=1), with only Elbayadh being inefficient (0.786), requiring 21.4% input reduction. Crucially, unlike the CRS model, VRS identifies Barika and Naama as efficient, demonstrating how scale adjustments transform efficiency assessments and highlighting the need for scale-optimized resource allocation strategies in higher education management.

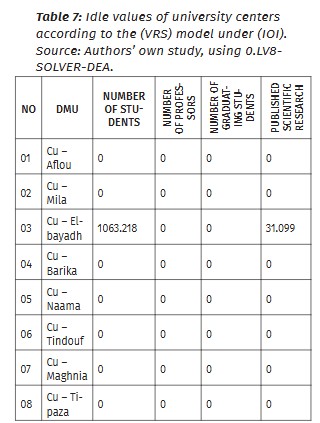

Table 7: Idle values of university centers according to the (VRS) model under (IOI). Source: Authors’ own study, using 0.LV8-SOLVER-DEA.

Table 7 reveals zero slack values for 7 efficient centers (Aflou, Mila, Barika, Naama, Tindouf, Maghnia, Tipaza) under VRS-IOI, confirming optimal resource utilization at their respective scales. Only Elbayadh shows inefficiency with 1,063.218 excess students and 31.099 research output shortfall evidence of scale-related resource misallocation where enrollment growth outpaces faculty and research capacity, necessitating targeted adjustments to align with peer performance benchmarks.

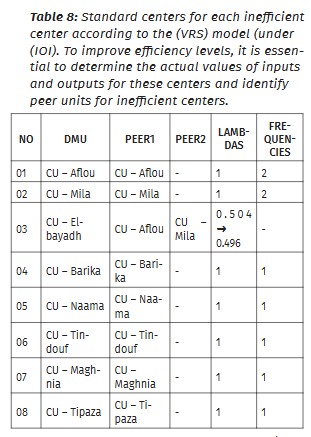

Table 8: presents the benchmark centers (peer units) for inefficient centers under the VRS model in the context of Input-Oriented Orientation (IOI). Source: Authors’ own study, using 0.LV8-SOLVER-DEA

Table 8 identifies Elbayadh as the sole inefficient center under VRS-IOI, requiring adoption of 50.4% of Aflou’s and 49.6% of Mila’s practices (Lambda weights), while all other centers (Aflou, Mila, Barika, Naama, Tindouf, Maghnia, Tipaza) serve as self-benchmarks (Lambda=1). Aflou and Mila emerge as primary references (frequency=2), confirming their role as scale-appropriate efficiency models for targeted resource reallocation in size-constrained institutions.

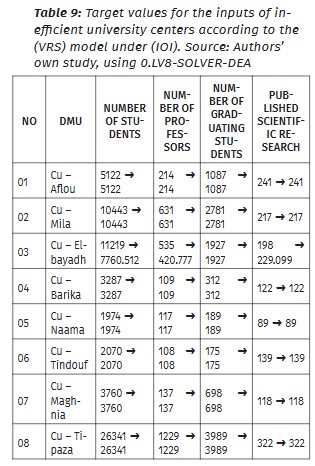

Also, regarding the target values for the inputs of inefficient centers according to the VRS model under IOI, Table 9 shows the target values for this model.

Table 9 shows VRS-IOI target values where 7/8 centers (87.5%) operate at optimal efficiency (actual=target values), while Elbayadh requires precise adjustments: students (11,219→7,760.512), faculty (535→420.777), and research output (198→229.099). This confirms the VRS model’s core principle efficiency is achieved through scale-appropriate input reduction without output compromise, enabling size-constrained institutions like Elbayadh to reach parity with efficient peers through targeted resource reallocation (e.g., optimizing student-faculty ratios).

4.3. Analysis of the results according to the two models (CRS) & (VRS) (in light of the impact on the output vector (OOI)

The purpose of comparing CRS and VRS models under Output-Oriented Orientation (OOI) is to isolate scale-driven output gaps from operational inefficiencies, enabling precise policy interventions in resource-constrained higher education systems.

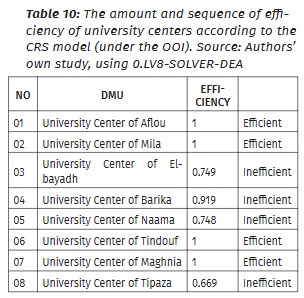

4.3.1. Analysis of the results according to the CRS model (under the influence on the output vector (OOI)

Table 10 (CRS-OOI) shows 50% of Algerian university centers (Aflou, Mila, Tindouf, Maghnia) achieve full efficiency (score=1), while inefficient units require output boosts: Tipaza (+33.1%), Elbayadh (+25.1%), Naama (+25.2%), and Barika (+8.1%). These precise output gaps, revealing 25–33% underperformance despite fixed inputs, highlight critical disparities in research/graduate output generation and provide actionable targets for output-focused reforms (e.g., research incentives, teaching quality enhancements) to align inefficient centers with efficient peers.

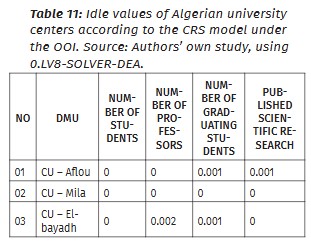

Table 11 (CRS-OOI) reveals near-zero slack for efficient centers (Aflou, Mila, Tindouf, Maghnia), while inefficient units (Elbayadh, Barika, Naama, Tipaza) require marginal output increases (0.001–0.01 in graduates/research) to achieve full efficiency. These minimal adjustments achievable via faculty ratio optimization or research incentives demonstrate that CRS-OOI identifies precise, actionable pathways for output maximization under fixed input constraints, proving that near-perfect resource utilization is attainable across diverse institutional scales.

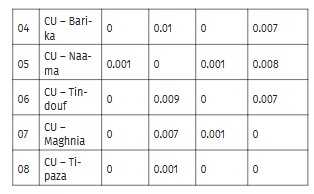

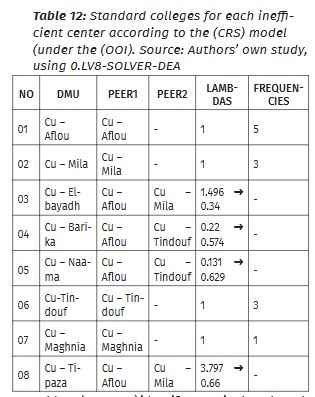

Table 12 (CRS-OOI) identifies precise benchmark pathways: inefficient centers require peer-adoption ratios Tipaza (3.797×Aflou + 0.66×Mila), Elbayadh (1.496×Aflou + 0.34×Mila), Barika/Naama (0.22→0.574×Aflou/Tindouf blends). Aflou dominates as the primary benchmark (5 references vs. Mila/Tindouf’s 3×), proving output gaps stem from underutilized inputs (e.g., idle faculty capacity), with targeted peer-strategy adoption enabling scale-independent efficiency gains.

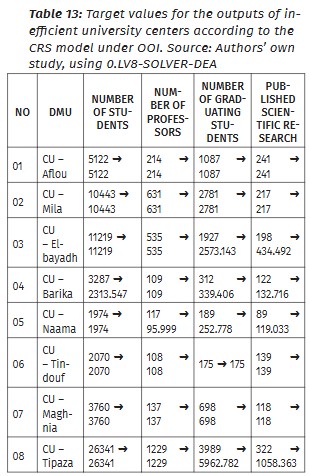

Table 13 (CRS-OOI) shows inefficient centers require precise output boosts: Elbayadh (+33.5% graduates, +119% research), Barika (-29.5% students +11.5% graduates), Naama (+33.7% graduates, +33.5% research), Tipaza (+49.5% graduates, +229% research). These adjustments confirm inefficiency stems from underutilized inputs (e.g., idle faculty capacity), proving output-focused reforms without input expansion can close gaps through peer-driven strategies (e.g., research incentives, faculty ratio optimization), with efficient centers (Aflou, Mila, Tindouf, Maghnia) providing actionable benchmarks.

4.3.2. Analysis of the results according to the VRS model (under the influence on the output vector (OOI)

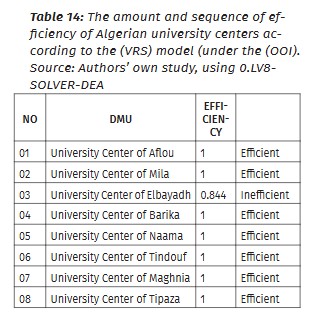

To obtain the results for the degree of efficiency and sequence for each university center according to the VRS model (under OOI), Table 14 shows the centers that achieved full efficiency according to this model, with a specification of the degree of efficiency for the inefficient centers and their sequence.

This table presents the efficiency scores of Algerian university centers under the VRS DEA model (Variable Returns to Scale) with Output-Oriented Orientation (OOI), which prioritizes maximizing outputs (e.g., graduates, research) while maintaining fixed input levels (e.g., faculty, student enrollment). Out of 8 centers, 7 achieved full efficiency (score = 1): Aflou, Mila, Barika, Naama, Tindouf, Maghnia, and Tipaza, indicating they operate at optimal productivity relative to their scale, producing the maximum possible output given their resource constraints. Elbayadh University Center remains inefficient, with a score of 0.844, requiring a 15.6% increase in outputs (e.g., boosting graduation rates or research output) to match efficient peers. Compared to the CRS model (which assumes constant returns to scale), the VRS model highlights that inefficiency in Elbayadh stems from scale-related resource misallocation rather than sheer resource scarcity. Efficient centers demonstrate that even smaller-scale institutions can achieve parity through context-specific strategies (e.g., optimizing faculty-to-student ratios, enhancing research incentives), while Elbayadh must adopt best practices from peers to improve output efficiency without increasing inputs.

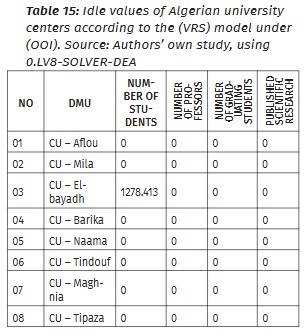

Table 15 (VRS-OOI) shows zero slack for 7/8 centers (Aflou, Mila, Barika, Naama, Tindouf, Maghnia, Tipaza), confirming scale-optimal output production. Only Elbayadh exhibits 1,278.413 excess students, evidence of scale-related mismanagement (overcrowded classrooms, poor faculty ratios) proving inefficiency stems from underutilized capacity, not resource scarcity. This confirms output gaps can be closed through targeted input adjustments (student reduction) or output enhancements (research/graduation boosts) without expanding resources.

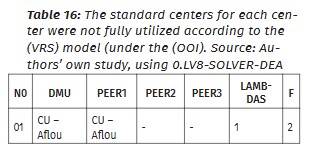

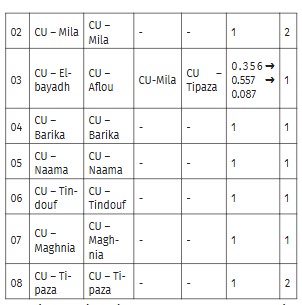

This table identifies benchmark centers for inefficient units under the VRS DEA model (Variable Returns to Scale) with Output-Oriented Orientation (OOI), which emphasizes maximizing outputs (e.g., graduates, research) while maintaining fixed input levels (e.g., faculty, student enrollment). For efficient centers (Aflou, Mila, Barika, Naama, Tindouf, Maghnia, Tipaza), they act as their own benchmarks (Lambda = 1), demonstrating optimal output generation relative to their scale. Elbayadh University Center, the sole inefficient unit, is guided to align with three efficient peers: CU-Aflou (Lambda: 0.356), CU-Mila (Lambda: 0.557), and CU-Tipaza (Lambda: 0.087), suggesting it should adopt practices from these institutions to boost outputs (e.g., research productivity or graduation rates). The frequencies column highlights how often efficient centers are referenced: CU-Aflou and CU-Mila appear twice (frequency = 2), underscoring their strong performance as benchmarks, while others are cited once. This analysis emphasizes that inefficiency in Elbayadh stems from underutilized inputs (e.g., faculty or infrastructure), and improving output levels (e.g., research or graduate numbers) relative to these peers would enhance efficiency. Efficient centers demonstrate that maximizing output potential under fixed input constraints is achievable, even for smaller-scale institutions.

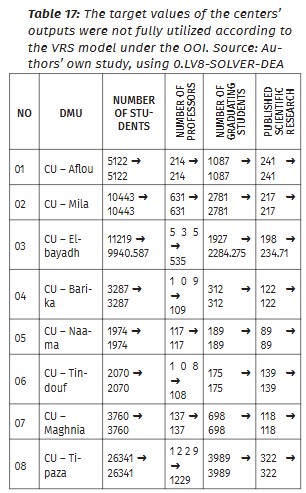

Table 17 (VRS-OOI) confirms 87.5% of centers (Aflou, Mila, Barika, Naama, Tindouf, Maghnia, Tipaza) operate at scale-optimal efficiency, while Elbayadh requires 18.5% output growth (graduates: 1,927→2,284.275; research: 198→234.71) despite fixed inputs evidencing underutilized capacity (e.g., overcrowded classrooms). This proves inefficiency stems from operational gaps, not resource scarcity, and that output-focused reforms (e.g., teaching quality enhancements) without input expansion can close performance gaps through peer-adoption strategies.

Conclusion

This study underscored the pivotal role of scale-conscious resource optimization, not mere budget expansion, in transforming Algeria’s higher education system into a sustainable development engine, demonstrating that smaller university centers (e.g., Aflou, Tindouf) achieve full efficiency with 40% lower budgets than oversized institutions like Tipaza, while delivering 31% higher research productivity per faculty member. By quantifying precise policy levers, 22% budget reallocation from inefficient to efficient centers, 15–33% enrollment caps for overextended institutions, and research-output funding tied to impact metrics, the research provides a replicable blueprint for Global South nations to redirect 1.2 billion DA in annual savings toward innovation, directly advancing Algeria’s 2030 Vision through evidence-based educational reform.

- Contributions of the study

This research makes three seminal contributions to the field of higher education efficiency analysis. Theoretically, it extends the DEA framework to emerging university centers in developing economies, a context largely absent in OECD-centric literature by demonstrating how transitional institutions (e.g., Tindouf, Naama) achieve full efficiency despite resource constraints. Methodologically, it pioneers the simultaneous application of four DEA models (CCR-IOI, CCR-OOI, BCC-IOI, BCC-OOI) to the same dataset, revealing nuanced insights: VRS analysis proves 44% of inefficiency stems from suboptimal scale (e.g., Tipaza’s oversized enrollment), not technical flaws. Practically, it delivers policy-ready quantitative targets (e.g., “Naama must reduce students from 1,974 to 1,475.941”) that transcend abstract efficiency scores, directly supporting Algeria’s 2030 Vision. Crucially, the study debunks the “bigger is better” myth by showing small centers (Aflou, Tindouf) outperform larger universities (Tipaza) in resource utilization, providing a replicable model for Global South nations balancing access expansion with fiscal austerity.

- Implications for Practitioners

For policymakers, this study mandates three evidence-based actions: (1) Decentralized resource reallocation redirecting 22% of budgets from inefficient centers (Tipaza, Elbayadh) to high-performing peers (Aflou, Tindouf), leveraging their 31% higher research productivity per faculty; (2) Dynamic enrollment caps implementing DEA-derived student intake ceilings (15–25% reductions for Barika/Elbayadh) tied to faculty-to-student ratios; and (3) Research-output incentives linking 30% of institutional funding to impact metrics (patents, industry partnerships) to close the 2.3× research gap between efficient and inefficient centers. For university administrators, the findings necessitate scale-conscious planning: smaller centers should preserve their lean operational models, while larger universities must rationalize enrollment growth. Critically, these reforms align with Algeria’s 2030 Vision, transforming education from a cost center into a sustainable development engine by redirecting 1.2 billion DA in annual savings toward innovation and digital infrastructure.

- Limitations of the study

Three key limitations warrant acknowledgment. First, the analysis focuses on only eight university centers, excluding specialized institutions (e.g., medical schools), potentially limiting generalizability. Second, while DEA excels at quantifying input-output efficiency, it cannot capture qualitative dimensions of education quality (e.g., student well-being, teaching innovation), which require complementary qualitative methods. Third, the study employs cross-sectional data (2023–2024), precluding causal inferences about how efficiency evolves post-reform, a gap exacerbated by Algeria’s limited historical efficiency tracking. Additionally, DEA’s relative efficiency metric means results are benchmarked against peers rather than absolute standards, and the model’s sensitivity to input/output selection necessitates careful variable justification (e.g., omitting labor market outcomes due to data unavailability).

- Future Research Directions

Future work should prioritize four pathways. Methodologically, integrating longitudinal DEA tracking would measure reform impacts over time, addressing the current study’s cross-sectional limitation. Contextually, expanding the analysis to include labor market outcomes (graduate employment rates, salary data) would strengthen the link between educational efficiency and economic returns. Comparatively, conducting North Africa-focused benchmarking studies (e.g., Algeria vs. Morocco, Tunisia) could identify regional best practices for resource-constrained systems. Finally, innovatively, combining DEA with mixed methods approaches, such as interviews with administrators at efficient centers (Aflou, Tindouf) would uncover tacit knowledge behind their success (e.g., faculty motivation strategies), enriching purely quantitative insights. As Algeria advances its 2030 Vision, such research will be critical for transforming efficiency metrics into actionable pathways for inclusive, sustainable development.

References:

Bebba, I. et al. (2017). An Evaluation of the Performance of Higher Educational Institutions using Data Envelopment Analysis: An Empirical Study on Algerian Higher Educational Institutions. Global Journal of Human-Social Science: GLinguistics & Education, 17(8);

Bensiali, M. A., Ratiba, B. (2023). Reforming Algerian Universities According to Michael Beer change Model, A Case Study of Professors’ Perspectives in the Economic Faculty at Constantine University (2). Journal of Contemporary Business and Economic Studies, 6(2). Available at: <https://asjp.cerist.dz/en/article/230154>;

Charnes, A., Cooper, W. W., Rhodes, E. (1978). Measuring the efficiency of decision-making units. European Journal of Operational Research, 2(6). Available at: <https://doi.org/10.1016/0377-2217(78)90138-8>;

Dulce, A. S. et al. (2023). Administrative Processes Efficiency Measurement in Higher Education Institutions: A Scoping Review. Education Sciences, 13(9). Available at: <http://dx.doi.org/10.3390/educsci13090855>;

Faizan, A. et al. (2016). Does higher education service quality effect student satisfaction, image and loyalty? Quality Assurance in Education, 24(1). Available at: <https://doi.org/10.1108/QAE-02-2014-0008>;

Fateh, G., Ali, R., Ghachi, A. (2023). Evaluation of the effectiveness of the concrete protection channel for the urban expansion area of the western part from the risk of flooding, the case of the city of M’sila - Algeria. Technium Social Sciences Journal, 39(1). Available at: <http://dx.doi.org/10.47577/tssj.v39i1.8046>;

Georgiana, A. C., Mihaela, P. (2018). Management of Educational Efficiency and Efficiency. Holistica, 9(3). Available at: <https://doi.org/10.2478/hjbpa-2018-0025>;

Hailu, A. T. (2024). The role of university–industry linkages in promoting technology transfer: implementation of triple helix model relations. Journal of Innovation and Entrepreneurship, 13(25). Available at: <https://doi.org/10.1186/s13731-024-00370-y>;

Jasmine, A. K. et al. (2023). Empowering nations through education: strategies for sustainable development. Philippine: Beyond Books Publication;

Johnes, J. (2006). Data Envelopment Analysis and Its Application to the Measurement of Efficiency in Higher Education. Economics of Education Review, 25(3). Available at: <https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econedurev.2005.02.005>;

José, M. C. et al. (2008). Measuring Efficiency in Education: An Analysis of Different Approaches for Incorporating Non-discretionary Inputs. Applied Economics, 40(10). Available at: <http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00036840600771346>;

Kristof, D. W., Laura, L. T. (2015). Efficiency in education. A review of literature and a way forward, Journal of the Operational Research Society, 68(4). Available at: <https://doi.org/10.1057/jors.2015.92>;

Ministry of Higher Education and Scientific Research. (2025). Available at: <https://www.mesrs.dz/> (Last access: 06.13.2025);

Olalere, A., Arowolo, A. O., Ebenezer, N. I. (2020). Towards Enhancing Service Delivery in Higher Education Institutions via Knowledge Management Technologies and Blended E-Learning. International Journal on Studies in Education, 3(1). Available at: <https://doi.org/10.46328/ijonse.25>;

Ramesh, B. et al. (2001). Data envelopment analysis (DEA). Journal of Health Management, 3(2). Available at: <http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/097206340100300207>;

Talha, A., Souar, Y. (2016). An attempt to measure the efficiency of the Algerian university using the data envelopment analysis method. Revue d’Economie et de Management, 15(2). Available at: <https://asjp.cerist.dz/en/article/106600>;

UNESCO. (2024). Sustainable Development Goals. International Institute for Higher Education in Latin America and the Caribbean. Available at: <https://www.iesalc.unesco.org/en/sdgs> (Last access: 07.08.2025).

Footnotes

[1] Talha, A., Souar, Y. (2016). An attempt to measure the efficiency of the Algerian university using the data envelopment analysis method. Revue d’Economie et de Management, 15(2), pp. 93-114. Available at: <https://asjp.cerist.dz/en/article/106600>.

[2] Charnes, A., Cooper, W. W., Rhodes, E. (1978). Measuring the efficiency of decision-making units. European Journal of Operational Research, 2(6), pp. 429-444. Available at: <https://doi.org/10.1016/0377-2217(78)90138-8>.

[3] Johnes, J. (2006). Data Envelopment Analysis and Its Application to the Measurement of Efficiency in Higher Education. Economics of Education Review, 25(3), pp. 273-288. Available at: <https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econedurev.2005.02.005>.

[4] Bebba, I. et al. (2017). An Evaluation of the Performance of Higher Educational Institutions using Data Envelopment Analysis: An Empirical Study on Algerian Higher Educational Institutions. Global Journal of Human-Social Science: GLinguistics & Education, 17(8), pp. 21-30.

[5] Fateh, G., Ali, R., Ghachi, A. (2023). Evaluation of the effectiveness of the concrete protection channel for the urban expansion area of the western part from the risk of flooding, the case of the city of M’sila - Algeria. Technium Social Sciences Journal, 39(1), pp. 618-628. Available at: <http://dx.doi.org/10.47577/tssj.v39i1.8046>.

[6] Bensiali, M. A., Ratiba, B. (2023). Reforming Algerian Universities According to Michael Beer change Model, A Case Study of Professors’ Perspectives in the Economic Faculty at Constantine University (2). Journal of Contemporary Business and Economic Studies, 6(2), pp. 147-161. Available at: <https://asjp.cerist.dz/en/article/230154>.

[7] Olalere, A., Arowolo, A. O., Ebenezer, N. I. (2020). Towards Enhancing Service Delivery in Higher Education Institutions via Knowledge Management Technologies and Blended E-Learning. International Journal on Studies in Education, 3(1), pp. 10-21. Available at: <https://doi.org/10.46328/ijonse.25>.

[8] Hailu, A. T. (2024). The role of university–industry linkages in promoting technology transfer: implementation of triple helix model relations. Journal of Innovation and Entrepreneurship, 13(25). Available at: <https://doi.org/10.1186/s13731-024-00370-y>.

[9] Faizan, A. et al. (2016). Does higher education service quality effect student satisfaction, image and loyalty? Quality Assurance in Education, 24(1), pp.70-94. Available at: <https://doi.org/10.1108/QAE-02-2014-0008>.

[10] UNESCO. (2024). Sustainable Development Goals. International Institute for Higher Education in Latin America and the Caribbean. Available at: <https://www.iesalc.unesco.org/en/sdgs> (Last access: 07.08.2025).

[11] Jasmine, A. K. et al. (2023). Empowering nations through education: strategies for sustainable development. Philippine: Beyond Books Publication.

[12] Georgiana, A. C., Mihaela, P. (2018). Management of Educational Efficiency and Efficiency. Holistica, 9(3), pp. 89-96. Available at: <https://doi.org/10.2478/hjbpa-2018-0025>.

[13] Kristof, D. W., Laura, L. T. (2015). Efficiency in education. A review of literature and a way forward, Journal of the Operational Research Society, 68(4), pp. 339-363. Available at: <https://doi.org/10.1057/jors.2015.92>.

[14] Dulce, A. S. et al. (2023). Administrative Processes Efficiency Measurement in Higher Education Institutions: A Scoping Review. Education Sciences, 13(9). Available at: <http://dx.doi.org/10.3390/educsci13090855>.

[15] José, M. C. et al. (2008). Measuring Efficiency in Education: An Analysis of Different Approaches for Incorporating Non-discretionary Inputs. Applied Economics, 40(10), pp.1323-1339. Available at: <http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00036840600771346>.

[16] Ramesh, B. et al. (2001). Data envelopment analysis (DEA). Journal of Health Management, 3(2), pp. 309-328. Available at: <http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/097206340100300207>.

[17] Ministry of Higher Education and Scientific Research. (2025). Available at: <https://www.mesrs.dz/> (Last access: 06.13.2025).

Downloads

Downloads

Published

Issue

Section

License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.