Rescuing Struggling Companies through Preventive Corporate Rescue Tools: Economic Implications of the French and Moroccan Special Mandate Models

DOI:

https://doi.org/10.35945/gb.2025.20.001Keywords:

Modern bankruptcy laws, preventive Procedures, special mandate, struggling companies, company rescue, economic outcomes, investment climateAbstract

This paper presents a comparative analysis of the “Special Mandate” as a preventive mechanism for rescuing struggling companies, focusing on French and Moroccan legislation. While existing studies focus on legal doctrine, this paper addresses a critical gap by linking these legal frameworks to their tangible economic outcomes, which is essential for evaluating their true effectiveness in the marketplace.

The analysis contrasts two divergent legislative philosophies. The French model is notably broad, applying to nearly all types of enterprises regardless of their legal form, reflecting a proactive stance on economic intervention. It provides detailed procedural rules governing the agent’s (mandataire ad hoc) appointment, potential conflicts of interest, and the precise scope of the mission.

Conversely, the Moroccan approach is significantly more restrictive, limiting the procedure mainly to commercial “traders” (commerçants) and containing legislative gaps that create procedural uncertainty for both debtors and creditors. While the procedure’s key advantages in both systems are its confidentiality and simplicity, its purely contractual nature presents a major limitation, as its success is entirely contingent upon voluntary creditor participation, which is often difficult to secure in distressed situations.

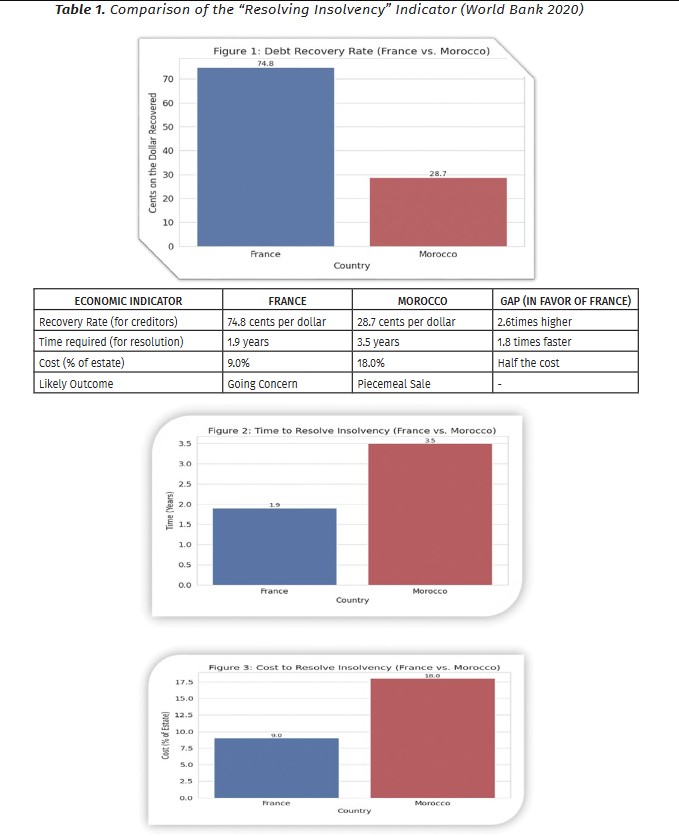

The paper concludes that the French model’s enhanced legal flexibility correlates with superior economic performance, evidenced by outcomes such as a 2.6-fold higher debt recovery rate, offering a clear, data-driven recommendation for legislative reform based on proven economic stability.

Keywords: Modern bankruptcy laws, preventive Procedures, special mandate, struggling companies, company rescue, economic outcomes, investment climate.

Introduction

In their efforts to improve the investment climate, nations strive to enhance the legal system that governs the economic sphere. For a long time, this system followed a singular path: simplifying and facilitating the establishment of companies to foster a strong economic fabric. However, fierce competition among these companies, on the one hand, and economic crises on the other, have expedited the need for nations to focus on an alternative path: ensuring the continuity of these companies by supporting and rescuing them. The cessation of these companies’ activities has negative consequences that extend beyond the economic sphere, such as the potential for other companies to default on their payments due to the non-payment of their debts, and a reduction in tax revenues for the public treasury, to the social sphere, namely, the layoff of workers.

The economic and social stakes are substantial. In 2024 alone, France registered a record 67,830 company failures, threatening 256,000 jobs. Similarly, Morocco saw over 15,658 firms enter insolvency proceedings in the same period, with the commerce and real estate sectors being most affected. These figures underscore the urgent need for effective rescue mechanisms.

This focus is embodied in the shift from old bankruptcy laws, which failed to achieve their objectives of protecting creditors and ensuring debt repayment, and which could only be realized by punishing the debtor company for what was considered an offense requiring a penalty, to modern bankruptcy laws. to modern bankruptcy laws. In some legislations, these are referred to as company rescue laws, the primary goal of which is to preserve the economic and social fabric by maintaining the company’s continuity and, consequently, safeguarding employment. The recovery of debts by creditors thus becomes a natural outcome of the company’s survival.

This legislative shift is not isolated; it is part of a distinct global trend. Nations are strategically reforming their laws in what has been termed “regulatory competition”[1] to attract international capital. This trend is echoed in the latest macroeconomic analyses. The International Monetary Fund (IMF, 2024),[2] in its recent Article IV consultation for France, emphasizes the resilience of the French economy, supported by a robust framework for corporate restructuring, which is crucial for post-pandemic recovery.

Similarly, the European Commission (2024),[3] in its in-depth review, links future economic performance to the efficient handling of corporate distress. This movement, once promoted by UNCITRAL, has now been codified at a regional level. The most significant recent development is the EU Directive 2019/1023 on Preventive Restructuring, which mandates all member states to adopt effective pre-insolvency frameworks, validating the very philosophy underpinning the French model.[4] Comparative studies on the transposition of this directive note that the established French model served as a key inspiration for the Directive’s emphasis on flexible, pre-judicial mechanisms.[5]

In this context, the importance of preventive measures in modern bankruptcy legislation has emerged as proactive tools aimed at saving viable enterprises rather than liquidating them. The “Special Mandate” is one of the most prominent of these measures, a confidential, preventive mechanism that originated in French judicial practice before being formally adopted by French and subsequently Moroccan legislators.

Therefore, this study, employing a comparative analytical methodology reinforced by economic data analysis, seeks to examine the nature of this procedure in French and Moroccan legislation. The objective is to distill insights that could aid in adopting an effective system for proactively addressing company difficulties by demonstrating how specific legislative choices in the Special Mandate procedure correlate with divergent economic outcomes.

This is particularly relevant given that the World Bank introduced a tenth indicator related to resolving insolvency in its 2017 Doing Business annual report – a report often relied upon by foreign investors in selecting a suitable investment environment.

This indicator reveals stark differences: France ranks 26th globally for resolving insolvency, while Morocco ranks 73rd. The economic implications of this gap are profound. France’s framework facilitates an average debt recovery rate of 74.8 cents on the dollar, compared to just 28.7 cents in Morocco. This study argues that these economic disparities are not accidental but are a direct consequence of the differing legal philosophies and mechanisms, such as the Special Mandate, adopted by each nation.

The study will address this through the following sections:

Part I: The Rules and Procedures for Appointing a Special Agent.

Section 1: Eligibility Criteria for the Special Mandate Procedure.

I - Personal Scope of Application for the Special Mandate Procedure (Condition of Legally

Defined Status).

II - Material Scope of Application for the Special Mandate Procedure (The Company’s

Situation).

Section 2: Rules About the Appointment of the Special Agent.

I - Procedures for Appointing the Special Agent and the Limits of the Court President’s

Authority.

II - Conflicts of Interest About the Special Agent.

Part II: The Legal Framework for the Special Agent’s Mission.

Section 1: The General Framework of the Special Agent’s Mission.

I - The Limits of the Special Agent’s Mission.

II - Determination of the Special Agent’s Remuneration.

Section 2: Advantages of the Special Mandate Procedure.

I - Confidentiality.

II - Flexibility and Simplicity.

Methodology

This research adopts a mixed-method approach, combining a comparative legal-doctrinal analysis with a quantitative assessment of economic outcomes. The primary methodology involves a doctrinal comparison of the French Commercial Code (Book VI) and the Moroccan Commercial Code (Law No. 73-17) concerning the Special Mandate. This legal analysis focuses on the scope, appointment procedures, and operational rules of the mechanism. To address the research gap, this legal analysis is supplemented by economic data from international and national bodies. The study utilizes:

- World Bank Data: Comparative statistics from the Doing Business 2020 report on the “Resolving Insolvency” indicator (e.g., recovery rates, time, cost) are used to quantify the efficiency of each legal system. (See Table 1 and Figures 1-3);

- Current Macroeconomic Reports: To supplement the 2020 World Bank data, this study incorporates recent (2024-2025) economic analysis and forecasts from the International Monetary Fund (IMF, 2024) and the European Commission (2024) to provide a current macroeconomic context;

- National Statistics: Data on firm failures and employment impact from sources like Altares (as cited in BPCE L’Observatoire, 2024)[6] and Inforisk (as cited in Le360.ma, 2025)[7] are used to establish the scale of the economic problem;

- Recent Peer-Reviewed & Legal Sources: To address the latest legal-doctrinal evolution, the analysis integrates recent (2021-2025) peer-reviewed articles and expert legal analysis (e.g., Gerasimova et al., 2024; Lancaster EPrints, 2025) focusing on the transposition of EU Directive 2019/1023 via France’s Ordinance No. 2021-1193, and its specific impact on preventive mechanisms (Sorbonne, 2024);

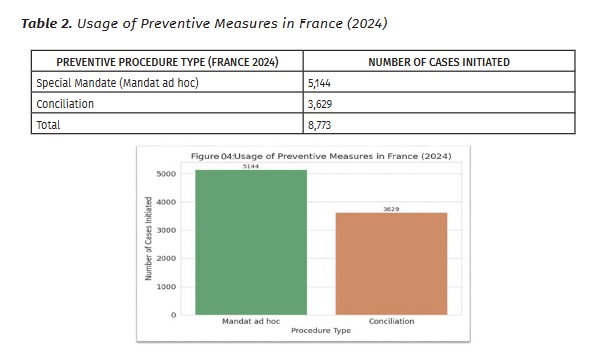

- Procedural Data: Statistics on the usage frequency of preventive measures in France (e.g., Mandat ad hoc) from the CNAJMJ are used to demonstrate the mechanism’s practical relevance. (see Table 2 and Figure 4).

The objective is to move beyond a purely descriptive legal comparison and demonstrate the correlation between legislative design and measurable economic performance.

Part I: Rules for and Procedures of the Appointment of a Special Agent

The special mandate was initially an experimental procedure that arose from the practice of French commercial courts, more specifically the Commercial Court of Paris, in 1990, during the real estate crisis, even in the absence of regulations governing it. However, some provisions related to it were later organized in Book VI of the French Commercial Code concerning business difficulties, under Article 04 of Law No. 94-475 of June 10, 1994, on the prevention and handling of business difficulties.[8] This was then supplemented by other provisions in Law No. 2005-845 of July 26, 2005, on the safeguarding of businesses.[9]

More significantly, this framework was substantially amended by the Ordinance of September 2021, which transposed the EU Directive 2019/1023 on Preventive Restructuring. This latest reform did not alter the core of the ‘Special Mandate’ (Mandat ad hoc) as a confidential and informal procedure. Instead, as legal analysis of the ordinance confirms (Sorbonne, 2024),[10] it reinforced its position. The reform intentionally preserved the Mandat ad hoc due to its proven effectiveness, solidifying its role within an integrated ecosystem that encourages early intervention.[11]

Moroccan legislation, which most closely follows French law among Arab legislations, established the possibility of appointing a special agent in the Law No. 15-95, which contains the Commercial Code.[12] It was then reaffirmed in the new effective Law No. 73-17 concerning difficulties of the undertaking,[13] given the importance of this procedure in addressing the difficulties faced by businesses.

French commercial law, and subsequently the Moroccan Commercial Code, legitimized the special mandate procedure after observing the positive results it had achieved since it was a judicial practice without legal basis. * This was an attempt to instill a culture of pre-emption, which requires time and trust to establish. The head of an enterprise who, years ago, would flee the court upon cessation of payments is now invited to knock on the judiciary’s door at the first sign of difficulties.[14]

From a legislative drafting perspective, neither the French nor Moroccan legislators provided a specific definition for the special mandate. Instead, they defined the limits of eligibility for the special mandate procedure (Section One) and the rules concerning the appointment of the special agent (Section Two). However, a comprehensive system for appointing the special agent is absent in the Moroccan Commercial Code, unlike in the French Commercial Code.

Section One: Eligibility Criteria for the Special Mandate Procedure

The Moroccan Commercial Code, following the model of the French Commercial Code, has defined the scope of application for the special mandate procedure. This scope is governed by two criteria that reflect the opinion of the legislators in both countries. The first criterion defines which persons can benefit from the special mandate procedure. In contrast, the second concerns the state of the enterprise that the legislation presumes the procedure can rectify.

I - Personal Scope of Application for the Special Mandate Procedure (Condition of Legally Defined Status)

The individuals who can benefit from the special mandate procedure are not different from those subject to prevention procedures, at least in French law. The latter has freed itself from classification and selectivity, considering that all persons influencing the economic landscape are concerned with internal and external prevention procedures alike.[15] This inclusive approach aligns with a broader European perspective favoring corporate innovation and diverse legal forms. This is detailed in Articles L611-2 and L611-2-1 of the French Commercial Code regarding the system of prevention procedures. The first article established the possibility for the President of the Commercial Court to summon the heads of commercial companies, economic interest groupings, and even individual commercial or craft enterprises to rectify the situation when it appears that the enterprise is suffering from difficulties that may threaten the continuity of its operations. The second article established the possibility for the President of the Judicial Court to summon the heads of private law legal entities and natural persons engaged in agricultural or independent professional activities, including liberal professions, for the same purpose of rectifying the enterprise’s situation whenever possible. This was summarized in Article L611-3 of the same law, which provides for the possibility for the President of the Commercial Court or the President of the Judicial Court,* As the case may be, to appoint a special agent upon the request of the debtor enterprise, which can be commercial, craft, or any other activity, considering that all enterprises, regardless of their nature, constitute the economic fabric of the state and thus require protection.

In contrast, Moroccan law has adopted a more restrictive legislative choice regarding the persons who can benefit from the special mandate procedure and the procedures included in the law on business difficulties in general.

This choice is evident in the special mandate procedure in Article 550 of the Moroccan Commercial Code. It makes the “undertaking” (maqawala), as defined in Article 546, the subject eligible for the special mandate procedure. The latter article presumes that the undertaking, in its individual or collective form, is a “trader” (tajir). This, in turn, means the exclusion of individual or collective undertakings of a civil nature, such as associations, cooperatives, economic interest groupings with a civil purpose, liberal professions, and others.

This restrictive legal-doctrinal choice has tangible economic consequences. By limiting preventive measures to ‘traders’, Moroccan law excludes a significant portion of the economy, which correlates with weaker performance in resolving insolvency. This is compounded by recent analyses showing the specific vulnerabilities of Moroccan firms to post-pandemic economic shocks,[16] often stemming from internal and external factors that preventive laws could address.[17] The World Bank’s 2020 data shows that Morocco’s framework results in a protracted 3.5-year resolution process with a low 28.7% recovery rate. In contrast, France’s broad personal scope is part of a legal philosophy that achieves a 74.8% recovery rate in just 1.9 years, making its economy more resilient and attractive to investors.

Therefore, the Algerian legislator, and other legislations that may adopt the special mandate procedure, should establish a personal scope that includes all enterprises contributing to development, away from unjustified selectivity based on commercial status. However, it may be advisable to initially limit the personal scope to the most significant enterprises and then expand it later, considering the necessary resources in the form of specialized agents and judges.

Finally, fulfilling a person’s legally defined status is not sufficient to initiate the special mandate procedure. Both French and Moroccan legislation require another condition related to the enterprise’s situation.

II - Material Scope of Application for the Special Mandate Procedure (The Company’s Situation)

Two questions have long been raised during debates on proposed laws concerning business difficulties in France: When is it appropriate to start dealing with the difficulties faced by enterprises? Moreover, how should they be characterized?[18] This means that different answers to these two questions, and consequently the different foundations associated with them, reflect the different approaches of bankruptcy legislation in determining the required state of the enterprise to open one procedure over another.

By examining the legislation under study, it can be said that they impose a condition related to the debtor enterprise’s situation for it to request the opening of the special mandate procedure. The scope of this situation is generally linked to a minimum threshold, which is the existence of difficulties that could threaten the continuity of the enterprise’s operations, and a maximum threshold, which is that the enterprise is not in a hopeless state, or what is usually expressed in different bankruptcy legislations as not having ceased payments for more than a specific period. Therefore, we will highlight the approaches adopted by the bankruptcy legislations under study on this issue regarding the special mandate procedure.

The general nature of the text of Article L611-3 of the French Commercial Code concerning the appointment of a special agent has made it a subject of many interpretations. Some have argued[19] that the request for the appointment of a special agent does not require any conditions related to the debtor enterprise’s situation. This means that the competent authority to which the request is submitted cannot refuse the appointment of a special representative because the debtor enterprise is in a state of cessation of payments unless the period of cessation of payments exceeds 45 days.* This view is supported by the possibility of reversing the cessation of payments during the special mandate procedure by agreeing with creditors to postpone the due dates of their debts within a short period from the procedure’s opening, especially in light of the French Court of Cassation’s interpretation of this delay.[20]

Others argue[21] that the debtor enterprise must not be in a state of cessation of payments when submitting its request for the appointment of a special agent, based on the plain reading of Article L611-3 of the French Commercial Code, which does not permit it. The special mandate procedure was designed as a preventive, not a curative, tool. This view is supported by the fact that the acceptance of appointing a special agent for an enterprise in a state of cessation of payments is not a certainty in judicial practice.

However, while the text of Article L611-3 of the French Commercial Code does not explicitly permit the appointment of a special agent for an enterprise in a state of cessation of payments, it does not exclude it either. Furthermore, the conciliation procedure* that the French legislator also designed it as a preventive measure. Initially, the person requesting this procedure was required not to be in a state of payment cessation, but this was soon allowed on the condition that the period of payment cessation did not exceed 45 days.[22]

Moreover, the uncertainty of accepting the appointment of a special agent for an enterprise in a state of cessation of payments in judicial practice may be due to the fact that such enterprises did not request the appointment of a special agent, not because the competent judicial authorities rejected their requests.

What can be concluded from this approach is that the French legislator has left a wide margin for actors in prevention to ensure sufficient flexibility for this procedure, given that debtor enterprises resort to it for its confidentiality, especially with the possibility of reversing the cessation of payments as indicated above. In our opinion, what supports this is that the provisions related to business difficulties have been and continue to be subject to amendments, the latest of which was in 2021. However, the generality of the article was not reviewed, even though the latest amendment affected it.[23]

In contrast, the possibility of appointing a special agent in the Moroccan Commercial Code is linked to the debtor enterprise facing difficulties in general that could disrupt its continuity, and specifically, social difficulties, those between partners, or those with the undertaking’s regular business partners.[24] This is on the condition that these difficulties have not led it to a state of cessation of payments.[25]

Therefore, the Algerian legislator and other legislations that may adopt the special mandate procedure should define the material scope of the procedure precisely. This could be done either by leaving the scope wide to ensure the required flexibility in this procedure, by allowing the targeted enterprises to request it even if they are in a state of cessation of payments for a specific period, or by defining the limits of eligibility by specifying the nature and level of the difficulties, such as setting the maximum limit as the enterprise’s cessation of payments.

Section Two: Rules Concerning the Appointment of the Special Agent

The appointment of the special agent is subject to legally defined formalities and controls that differ between the comparative legislations under study, as are the limits of the authority granted to the court’s President within these frameworks.

I - Appointment Procedures for the Special Agent and the Limits of the Court President’s Authority

Article 549 of the Moroccan Commercial Code authorizes the President of the court to appoint a special agent and entrust them with the mission of intervening to mitigate objections and resolve the difficulties the enterprise is facing. This occurs when it becomes clear to the President—after hearing the head of the enterprise and forming a clear view of its situation—that the agent can resolve the difficulties and mitigate the objections that hinder the enterprise’s continuity, especially those related to partners or regular business associates of the enterprise.[26]

However, the Code restricts the possibility of appointing a special agent by requiring that the head of the enterprise propose them.* This is based on the rationale that the latter will be more serious in seeking solutions, leading them to choose who they see as the most competent for the task, and because doing otherwise would exacerbate the difficulties by burdening the enterprise with new fees.[27] In contrast, the issue of the limits of the court president’s authority to accept or reject this proposal remains a legislative vacuum in Moroccan law.

Before this, the French legislator, through Article L611-3 of the French Commercial Code, allowed the President of the court to appoint a special agent upon the request of the debtor enterprise. The request must be submitted in writing by the legal representative of the legal person or by the natural person debtor to the President of the Commercial Court or the Judicial Court—as the case may be—within whose jurisdiction its headquarters is located, or, where applicable, within whose jurisdiction the natural person debtor has declared the address of their enterprise or activity.[28]

The request is filed with the court clerk’s office along with documents that clarify the applicant’s financial situation. The request must include the grounds on which it is based, the applicant’s identity, and a summary specifying the type of activity, number of employees, turnover, and results, the difficulties encountered, the measures to be taken for continuity, and justifying how the appointment of a special agent would allow for the resolution of the difficulties. It must also affirm that the enterprise is not in a state of cessation of payments. The applicant may also include in the request the name of the person they propose for the mission.[29]

However, this proposal is not binding on the President of the court, who remains free to accept or reject the name of the proposed agent, as well as the freedom to accept or reject the appointment request as a whole, which is embodied in a decision they issue.* This decision, according to the provisions of Article R611-20* of the French Commercial Code, is subject to appeal by the debtor in accordance with the provisions of Article R611-26 of the same Code. This article stipulates that the debtor submits or sends the appeal by registered letter with acknowledgment of receipt to the court clerk. The court president rules on the appeal within five days of its submission, after which the debtor is notified, regardless of the decision.

While the court president’s authority to accept or refuse the appointment of a special agent—without considering the proposed name—is justified by being linked to their conviction about the special agent’s ability to mitigate objections and resolve the enterprise’s difficulties, some argue that the discretionary power left to the President to accept or refuse the debtor’s proposal is inappropriate. This is not only in view of the voluntary and spontaneous nature of the debtor’s request but also due to the trust required for success in such a mission. They argue, in contrast, that it would be more appropriate to require the President of the court to accept the debtor’s choice or, at the very least, compel them to justify their refusal of the proposed person. The refusal of the debtor’s proposal could be an exceptional measure to make the plan more effective, especially since the debtor may be prepared to reject the intervention of an agent other than the one they proposed, by requesting the judge to terminate that agent’s mission under the provisions of Article R611-21 of the French Commercial Code.[30] Furthermore, the latter law specifies the conflicts of interest related to the special agent to ensure their neutrality.

II - Conflicts of Interest Pertaining to the Special Agent:

In practice, special agents, as well as conciliators, are often former consultants, lawyers, former judges, administrators, agents, or retired accountants, etc., due to their competence and knowledge of companies and business. This makes it possible to appoint a person who was providing a service to the debtor enterprise, or even an employee, during the period preceding the appointment, which could undermine the neutrality required by their function and discourage creditors from responding to their requests.[31]

Therefore, to avoid conflicts of interest and to ensure the required independence that the special agent needs while performing their negotiation-based mission, the French legislator, unlike the Moroccan legislator, has prohibited the appointment of a group of persons as a special agent. Article L611-13 of the French Commercial Code stipulates that the duties of a special agent may not be performed by a person who has received, in any capacity, directly or indirectly, remuneration or payments from the debtor enterprise.* From any creditor of the debtor enterprise, or any person under its control as defined by Article L 233-16 of the French Commercial Code.[32] An exception is made if the person has received such remuneration under a special mandate or a judicial mandate entrusted to them in the context of an amicable settlement or a conciliation procedure concerning the same debtor enterprise or its creditors. Also included in the exception is remuneration received by a person under a judicial mandate, other than the commissioner for the execution of the plan, in the context of a reorganization* or judicial settlement* Procedure.

In the same context, the article also provides that the duties of a special agent cannot be entrusted to a consular judge* who is currently in office or who has left office for less than five years.

Suppose the President of the court appoints the special agent. In that case, the court clerk notifies the concerned person of their appointment as a special agent by letter, accompanied by a letter containing the text of Article L611-13 on conflicts of interest. Upon accepting the appointment, the special agent must declare on their honor that they do not fall within the prohibitions of its text. They, in turn, inform the President of the court of their acceptance of the appointment.[33] And then begin their mission as special agents to mitigate the objections facing the enterprise.

Based on the foregoing, should the Algerian legislator, and other legislations thereafter, adopt the special mandate procedure, they are called upon to regulate all matters related to the appointment of the special agent, from the appointment procedures and modalities, through the determination of the powers granted to the competent judicial authorities in this regard, to the definition of conflicts of interest related to the special agent, in order to ensure the latter’s neutrality.

Part II: The Legal Framework for the Special Agent’s Mission

Like the French Commercial Code, the Moroccan Commercial Code has defined the general framework for the special agent’s mission (Section One) to ensure that their duties do not overlap with those of the enterprise’s management bodies. It has also worked to embody advantages within the special mandate procedure (Section Two) that are intended to support the success of the special agent’s mission.

Section One: The General Framework of the Special Agent’s Mission

In this section, we will clarify the mission of the special agent by explaining its limits. We will then address the criteria and conditions for determining the remuneration—the fees—that the special agent receives for carrying out their mission.

I - The Limits of the Special Agent’s Mission

The French Commercial Code, under Article L611-3, stipulates that the court president appoints a special agent whose mission he defines. Similarly, Article R611-19 of the same law confirms that the order of the court president appointing the ad hoc agent specifies their mission.

In the same context, the Moroccan Commercial Code[34] stipulates that the President of the court is authorized to appoint the special agent and define their mission and duration, considering that the special agent’s tasks vary depending on the size of the enterprise, the type of its activity, and even the nature of the difficulties it faces.

This means that the court’s President determines the content and duration of the special agent’s mission in the order he issues for their appointment, which corresponds precisely to the debtor enterprise’s request and needs.

Generally, the special agent’s mission has three main stages. In the preparation stage, the special agent undertakes to understand the enterprise’s situation and obtain a general overview to prepare an action plan in coordination with the debtor. This enables them to negotiate with the concerned parties in the second stage.[35] In this context, the first paragraph of Article L611-3 of the French Commercial Code provides that the decision appointing the special agent, when made, is sent to the statutory auditors to facilitate their access to information that helps them form an idea of the enterprise’s situation and identify its strengths and weaknesses, which may lead them to identify the causes of the difficulties and work to resolve them in a later stage.

In the second stage, the special agent and the debtor enterprise, through their representatives, begin negotiations with the concerned parties. This may be internal with the enterprise’s main partners or external with its regular associates or main creditors, including banks. The substance of these negotiations may involve negotiating deadlines and/or debt reductions. In the same context, the agent may suggest finding a partner to invest funds if an agreement for existing shareholders to inject new funds cannot be reached.[36] They may also propose restructuring the enterprise or selling a part of it.[37]

It is important to note at this stage that the work of the special agent does not affect the powers and obligations of the enterprise owner. The latter retains their authority and continues to manage the business without being stripped of it, while receiving the assistance of the special agent who cannot substitute for them. The role of the special agent is to help the head of the enterprise restore confidence in the enterprise from both shareholders and creditors. At the same time, the special agent must inform the President of the court who appointed them through periodic reports, updating them on the state of the business, its development prospects, and any difficulties encountered.[38]

The court president may find from the special agent’s reports that the success of the mission is linked to extending its deadline or replacing the agent. He may then extend the deadline or replace the agent, as the case may be, all after obtaining the consent of the enterprise owner.[39]

In a final stage, the special agent seeks to conclude an agreement that makes it possible to ensure the enterprise’s continuity by preserving its activity and associated employment. This is done by bridging the gap between what the concerned enterprise facing difficulties can agree to and what the main creditors can accept.[40]

The special agent’s mission ends upon its completion—the conclusion of the agreement—or at the end of the period specified in the order by the President of the court, unless it is extended based on the progress of the work.*

Ultimately, the special agent’s mission remains subject to the discretion of the debtor enterprise. Whenever it appears to them that the special mandate is not sufficient to achieve the desired continuity, they may request the President of the court to terminate the special agent’s mission, which the agent must then end immediately.[41]

II - How the Special Agent’s Remuneration is Determined

Unlike the Moroccan Commercial Code, the French Commercial Code regulates how the special agent’s remuneration is determined, moving away from a fee schedule and allowing for contractual freedom. This is the case even though practice confirms that the determination of the special agent’s fee *is often done by agreements between the debtor enterprise and the special agent before the request to open the special mandate procedure is submitted to the President of the competent court.[42]

The French Commercial Code has entrusted the competent court president with the task of determining the criteria for the special agent’s remuneration and its maximum amount, and, where applicable, its sum or method of payment.[43] This is done through an appealable order.* issued at the time of the special agent’s appointment, in light of the diligence required to accomplish the mission, and after taking the opinion of the public prosecutor. *Moreover, the consent of the debtor enterprise must be obtained, which is recorded in writing and attached to the appointment order.[44] However, the remuneration may not be linked to the amount of debt write-offs obtained, nor can it be a lump sum for opening the file.[45]

The possibility of reconsidering the remuneration remains. The special representative’s fee during their mission may prove insufficient because the work that needed to be done was more significant than what was initially planned. Whenever the special agent finds that the maximum remuneration set by the order is insufficient, they inform the President of the court. The latter then determines, if necessary, the new terms of remuneration in agreement with the debtor enterprise and, after taking the opinion of the public prosecutor, if conciliation is used to determine the new terms regarding the agent’s fees. If no agreement is reached on the latter, the special agent’s mission ends.[46]

At the end of the mission, based on the services rendered, the President orders the payment of the special agent’s remuneration by an order.[47]

Section Two: Advantages of the Special Mandate Procedure

The special mandate procedure is characterized by several advantages that contribute to the success of the special agent’s mission. It allows the head of the enterprise to, in complete confidentiality, enlist a specialized person to assist in resolving the difficulties facing their enterprise with great simplicity and flexibility.

I - Confidentiality

The procedures for appointing a special agent and their performance of the mission demand confidentiality. The spread of news about the appointment of a special agent for an enterprise could lead business partners to cease dealing with it, or it could cause some creditors to suddenly resort to individual actions to protect their rights, thereby exacerbating the difficulties and widening the gap between the enterprise and its partners. All of this complicates the special agent’s task or renders it futile. Conversely, the commitment of all actors in the special mandate procedure to confidentiality contributes to the success of the special agent’s mission. Therefore, the French Commercial Code stipulates that anyone summoned to the proceedings related to the special mandate, as well as anyone who becomes aware of it by virtue of their function, must maintain confidentiality.[48]

Inspired by French legislation, Moroccan legislation has adopted this feature as an important element. It also enshrines the necessity of maintaining the confidentiality of the special mandate procedure in all its stages: from the court president’s summons of the head of the enterprise through the appointment procedures for the special agent to the latter’s performance of their duties.[49]

It should be noted that non-compliance with the confidentiality obligation constitutes a fault that subjects the violator to paying damages to compensate for the harm caused by the breach, in accordance with the general rules of civil liability. This is unlike the breach of professional secrecy, for which applicable legislation imposes criminal penalties, as it is considered a crime.[50]

Alongside this, the principle of confidentiality should not undermine the trust between the actors in the special mandate procedure, such as the head of the enterprise using it to gain financial advantages from their partners, especially lenders.* On the other hand, the head of the enterprise must earn the trust of the enterprise’s partners by entrusting them with all useful information about the enterprise to allow the concerned parties first to understand the origin of the difficulties, and then work to find prospects for resolving them through agreements that preserve everyone’s interests. In other words, as much as confidentiality is necessary in the special mandate procedure to protect the enterprise facing difficulties, the dissemination of transparent information within a limited and defined circle must be allowed, which is essential for fair negotiation.[51]

II - Flexibility and Simplicity

This is evident in the special mandate procedure through its contractual nature, which is embodied by the few provisions that regulate its course compared to other amicable preventive and curative procedures.* Furthermore, these few provisions have made the debtor enterprise, through its representatives, the main controller of the procedure during most of its stages. The submission of a request to open the special mandate procedure and appoint the special agent depends on the will of the debtor enterprise through its legal representative; no other party can compel it to do so. It can also invite specific creditors to the procedure and not others, on the grounds that the objections against the enterprise came from them, or because the enterprise believes they are best able to support it due to their connection to it, or the mutual trust between them. The participation of these creditors remains subject to their own will.

Flexibility and simplicity are also apparent in the fact that the law does not define the special agent’s mission, unlike the mission of the conciliator.* In the conciliation procedure. Instead, this is left to the President of the competent court, who defines the special agent’s mission to perfectly suit the debtor’s request and the enterprise’s needs without conflicting with the will of its management. In addition, the special agent’s mission is not limited to a specific duration; the latter is determined according to the nature of the mission, the size of the enterprise, and other factors.

In the same vein, only the enterprise, through its representatives, has the right to terminate the procedure at any time it deems appropriate, even if the special agent’s mission has not ended, by informing the competent court president, who will then terminate the procedure immediately, as previously mentioned.

This combination of confidentiality and flexibility has made the Special Mandate a cornerstone of the French preventive system, not just in theory but in practice. This heavy reliance on preventive, out-of-court mechanisms demonstrates a widespread “culture of pre-emption” and trust in the system, a key factor in its economic success. In 2024, French courts initiated 5,144 Mandat ad hoc procedures and 3,629 Conciliation procedures (CNAJMJ, 2025).

Despite the advantages of the special mandate procedure, its limits, primarily drawn by its contractual nature, give rise to some shortcomings. These include the impossibility of preventing creditors who are not parties to the agreement from continuing to sue the debtor enterprise, a common challenge in pre-insolvency frameworks across the EU before recent reforms.[52] It also does not provide any additional guarantee to the creditors who are committed within the agreement, as it is not subject to approval by the competent judicial authority. This may create an urgent need for another procedure that blends a contractual nature with a degree of judicial control, such as the conciliation procedure.

Based on the foregoing, should the Algerian legislator and other legislations thereafter adopt the special mandate procedure, they are called upon to regulate the legal framework of the special agent’s mission. This should be done by defining the limits of this agent’s mission to ensure no overlap between their tasks and the tasks of the enterprise’s managers during the procedure, as well as by clarifying the criteria and methods used to determine the special agent’s fees in all cases. In all this, a sufficient degree of flexibility and simplicity should be ensured, alongside imposing the required confidentiality in the procedure, to make it an attractive option for managers of enterprises facing difficulties to the extent legally defined.

Conclusion

In conclusion to this comparative study, it is evident that the special mandate procedure represents a vitally important preventive tool, granting enterprises facing difficulties an opportunity to overcome them within a framework of confidentiality and flexibility. The comparison between the French and Moroccan experiences has revealed two different philosophies. The French legislator has adopted a broad and flexible approach, both in terms of the scope of beneficiaries and the assessment of the enterprise’s situation, while establishing detailed procedural rules that guarantee the rights of all parties. In contrast, the Moroccan approach has been characterized by a relative restriction in the procedure’s scope of application. There are some legislative vacuums concerning the judge’s authority and the conflicts of interest related to the agent.

The success of this procedure hinges on achieving a delicate balance between its contractual nature, which grants it flexibility, and the establishment of a clear legal framework. However, the key finding of this study is that the French model’s success is not merely legal; it is economic. The French framework’s flexibility directly correlates with superior economic outcomes: a 2.6-fold higher debt recovery rate, a process that is nearly twice as fast, and an outcome that favors business continuity rather than piecemeal liquidation, when compared to the more restrictive Moroccan model.

Accordingly, this study recommends that the Algerian legislator and other legislations, when adopting such a procedure, should draw inspiration from the French experience, not only for its legal comprehensiveness but for its proven economic results.

The establishment of such mechanisms not only contributes to rescuing enterprises but also instills a culture of pre-emption and early recourse to the judiciary, which enhances confidence in the economic climate and supports its stability by providing a credible, efficient path for investors and creditors to recover value, as evidenced by France’s high-performing insolvency indicators. This aligns with a growing international consensus that efficient, modern insolvency laws are critical infrastructure for economic renewal, investment, and sustainable (OECD, 2022; EBRD, 2022; UNCTAD, 2024).

Based on the foregoing, we present the following recommendations:

- Establish a personal scope that includes all enterprises contributing to development, avoiding unjustified selectivity based on commercial status. However, it may be advisable to start by limiting the scope to the most significant enterprises before expanding it later, considering the necessary resources in the form of specialized agents and judges;

- Regulate all matters related to the appointment of the special agent, starting from the appointment procedures and modalities, through the determination of the powers granted to the competent judicial authorities in this regard, to the definition of conflicts of interest related to the special agent, to guarantee the latter’s neutrality;

- Define the legal framework for the special agent’s mission by specifying its limits to ensure no overlap between their tasks and the tasks of the enterprise’s managers during the procedure. Clarify the criteria and methods used to determine the special agent’s fees in all cases. In all this, a sufficient degree of flexibility and simplicity should be ensured, alongside imposing the required confidentiality in the procedure, to make it an attractive option for managers of enterprises facing difficulties to the extent legally defined.

References:

Normative Acts:

Law No. 94-475 of June 10, 1994, on the prevention and treatment of business difficulties. (1994, June 11). JORF No. 134;

Law No. 2005-845 of July 26, 2005, on the safeguarding of businesses. (2005, July 27). JORF No. 173;

Law No. 15.95 on the Commercial Code, promulgated by Dahir No. 1-96-83 of August 1, 1996. (1996, October 3). Official Gazette of the Kingdom of Morocco, No. 4418;

Law No. 73.17 repealing and replacing Book V of Law No. 15.95 on the Commercial Code, regarding business difficulty procedures, promulgated by Dahir No. 1.18.26 of April 19, 2018. (2018, April 23). Official Gazette of the Kingdom of Morocco, No. 6667;

Law No. 2019-222 of March 23, 2019, for the 2018-2022 programming and justice reform. (2019, September 19). JORF No. 0218;

Ordonnance n° 2021-1193 portant modification du livre VI du code de commerce. Journal Officiel de la République Française, n° 0216 (16 septembre 2021), texte n° 2.

Literature:

Balemaken, E. L. R. (2013). The judge and the rescue of businesses in difficulty in OHADA law and French law: A comparative study. Doctoral thesis, Université Panthéon-Assas;

Bouquet, B. (2008, January/February). Ad hoc mandate and conciliation: a renovated legal tool. R J C, (1), 4;

BPCE L’Observatoire. (2024, October). Business failures in Q3, 2024;

CNAJMJ. (2025, January). Indicateurs – Procédures collectives et de prévention - Année 2024. Conseil National des Administrateurs Judiciaires et des Mandataires Judiciaires;

Coquelet, M.-L. (2017). Businesses in difficulty, payment and credit instruments (6th ed.). Dalloz;

Court of Cassation, Commercial Chamber. (2012, February 7). Judgment No. 10-28.815, 10-28.816] [Unpublished]. <www.legifrance.gouv.fr/juri/id/JURITEXT00002535783>;

Delebecque, P., Germain, M. (2011). Comprehensive Commercial Law: Commercial Instruments, Banks and Stock Exchanges, Commercial Contracts, Collective Proceedings (Part II; A. Moukalled, Trans.). University Establishment for Studies, Publishing and Distribution;

Depoix-Robain, N. (1997). The amicable settlement of business difficulties. Doctoral thesis, University Paris IX Dauphine;

Ech-Chafi, I., Ait Ali, E. H. (2024). Causes et conséquences de la défaillance des entreprises marocaines: Un état de l’art. African Scientific Journal, 3(27);

El Kettani, S., Bakkali, I. (2025). The impact of COVID-19 pandemic on Moroccan firms’ performance: A pre- and post-crisis comparative analysis. Learning Gate, 5(1);

European Commission. (2022). Insolvency Frameworks across the EU: Challenges after COVID-19 (Discussion Paper 182);

European Commission. (2024). Commission Staff Working Document: In-Depth Review 2024 - France;

Gerasimova, T. G., Galkina, A. S., Kartaeva, K. L., Kholopova, V. V. (2024). Corporate insolvency laws in selected jurisdictions: US, England, France, and Germany—A comparative perspective. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 17(3). <doi.org/10.3390/jrfm17030120>;

Guillonneau, M., Haehl, J.-P., Munoz-Perez, B. (2013). The prevention of business difficulties through ad hoc mandate and conciliation before commercial courts from 2006 to 2011. Ministry of Justice;

International Monetary Fund (IMF). (2024). France: 2024 Article IV Consultation—Staff Report. IMF Country Report No. 2024/219. Washington, D.C.;

Koehl, M. (2019). Negotiation in the law of businesses in difficulty. Doctoral thesis, Université Paris;

Lancaster University (Lancaster EPrints). (2025). The transposition of the Preventive Restructuring Directive (2019/1023) in France and Germany;

Latham & Watkins. (2021, September 20). France Publishes Restructuring and Insolvency Law Reform Ordinance;

Le360.ma. (2025, June 16). Entreprises: un nombre record de faillites au Maroc en 2024 [Enterprises: a record number of bankruptcies in Morocco in 2024];

Legal 500. (2024). France: Restructuring & Insolvency – Country Comparative Guides;

Möslein, F. (2021). Corporate asset locks: A comparative and European perspective. French Journal of Legal Policy;

Saint-Alary-Houin, C. (2020). Law of businesses in difficulty (12th ed.). LGDJ, Domat.;

Schmidt, J. (2023). Preventive restructuring frameworks: Jurisdiction, recognition and applicable law. International Insolvency Review, 32(3). <doi.org/10.1002/iir.1518>;

Schwartz, M. G. (2013). The concept of the ad hoc mandate. Doctoral thesis, University of Poitiers;

Shamaia, A. (2018). *Sharh Ahkam Nizam Mu’alajat Sa’ubat al-Muqawala fi Daw’ al-Qanun 17-73* [Explanation of the Provisions of the System for Handling Undertaking Difficulties in Light of Law 17-73]. Dar Al-Afaq Al-Maghribia;

Toh, A. (2015). The prevention of business difficulties: A comparative study of French law and OHADA law. Doctoral thesis, University of Bordeaux;

UNCTAD. (2024). World Investment Report 2024. United Nations Conference on Trade and Development;

Université Paris 1 Panthéon-Sorbonne (IEJ). (2024). Introduction to French Bankruptcy Law (Analysis of Ordinance 2021-1193);

Valdman, D. (2008, January 23–24). Safeguard law: which procedure for which business difficulties? Strategic choices. Gazette du Palais, 1, 14;

World Bank. (2020). Doing Business 2020: Comparing Business Regulation in 190 Economies. The World Bank.

[1] Schmidt, J. (2023). Preventive restructuring frameworks: Jurisdiction, recognition and applicable law. International Insolvency Review, 32(3), pp. 427-447. <doi.org/10.1002/iir.1518>.

[2] International Monetary Fund (IMF). (2024). France: 2024 Article IV Consultation—Staff Report. IMF Country Report No. 2024/219. Washington, D.C.

[3] European Commission. (2024). Commission Staff Working Document: In-Depth Review 2024 - France.

[4] Gerasimova, T. G., Galkina, A. S., Kartaeva, K. L., Kholopova, V. V. (2024). Corporate insolvency laws in selected jurisdictions: US, England, France, and Germany—A comparative perspective. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 17(3), p. 120. <doi.org/10.3390/jrfm17030120>.

[5] Lancaster University (Lancaster EPrints). (2025). The transposition of the Preventive Restructuring Directive (2019/1023) in France and Germany.

[6] BPCE L’Observatoire. (2024, October). Business failures in Q3, 2024.

[7] Le360.ma. (2025, June 16). Entreprises: un nombre record de faillites au Maroc en 2024 [Enterprises: a record number of bankruptcies in Morocco in 2024].

[8] Law No. 94-475 of June 10, 1994, on the prevention and treatment of business difficulties. (1994, June 11). JORF No. 134.

[9] Law No. 2005-845 of July 26, 2005, on the safeguarding of businesses. (2005, July 27). JORF No. 173.

[10] Université Paris 1 Panthéon-Sorbonne (IEJ). (2024). Introduction to French Bankruptcy Law (Analysis of Ordinance 2021-1193).

[11] Latham & Watkins. (2021, September 20). France Publishes Restructuring and Insolvency Law Reform Ordinance; Legal 500. (2024). France: Restructuring & Insolvency – Country Comparative Guides.

[12] Law No. 15.95 on the Commercial Code, promulgated by Dahir No. 1-96-83 of August 1, 1996. (1996, October 3). Official Gazette of the Kingdom of Morocco, No. 4418.

[13] Law No. 73.17 repealing and replacing Book V of Law No. 15.95 on the Commercial Code, regarding business difficulty procedures, promulgated by Dahir No. 1.18.26 of April 19, 2018. (2018, April 23). Official Gazette of the Kingdom of Morocco, No. 6667.

* For example, the number of times a special agent was appointed between 2006 and 2012 in France in commercial courts reached nearly 5,900 appointments. The acceptance rate of requests for the appointment of a special agent by the presidents of commercial courts alone in the same period reached 84.2%. For more statistics on the special mandate during the period 2006-2012, see Guillonneau, M., Haehl, J.-P., Munoz-Perez, B. (2013). The prevention of business difficulties through ad hoc mandate and conciliation before commercial courts from 2006 to 2011. Ministry of Justice.

[14] Schwartz, M. G. (2013). The concept of the ad hoc mandate. Doctoral thesis, University of Poitiers, p. 193.

[15] Möslein, F. (2021). Corporate asset locks: A comparative and European perspective. French Journal of Legal Policy.

* In French law, the High Court (tribunal de grande instance) has been replaced by the Judicial Court (tribunal judiciaire) through the law on programming and justice reform, pursuant to Ordinance No. 2019-964 of September 18, 2019, taken in application of Law No. 2019-222 of March 23, 2019, for the 2018-2022 programming and justice reform. (2019, September 19). JORF No. 0218.

[16] El Kettani, S., Bakkali, I. (2025). The impact of COVID-19 pandemic on Moroccan firms’ performance: A pre- and post-crisis comparative analysis. Learning Gate, 5(1).

[17] Ech-Chafi, I., Ait Ali, E. H. (2024). Causes et conséquences de la défaillance des entreprises marocaines: Un état de l’art. African Scientific Journal, 3(27).

[18] Depoix-Robain, N. (1997). The amicable settlement of business difficulties. Doctoral thesis, University Paris IX Dauphine. p. 61.

[19] Toh, A. (2015). The prevention of business difficulties: A comparative study of French law and OHADA law. Doctoral thesis, University of Bordeaux, p. 178.

*Because after this period, the competent judicial body will have no other option but to initiate judicial settlement or liquidation proceedings, as the case may be.

[20] Valdman, D. (2008, January 23–24). Safeguard law: which procedure for which business difficulties? Strategic choices. Gazette du Palais, 1, 14.

[21] Coquelet, M.-L. (2017). Businesses in difficulty, payment and credit instruments (6th ed.). Dalloz, p. 189.

* It is a preventive procedure that allows managers of enterprises facing difficulties to find simple and quick amicable solutions embodied in a confidential agreement to restore their enterprise’s situation.

[22] L611-4, C. Com, Fr.

[23] Ibid., L611-3, Modified by Ordinance No. 2021-1193 of September 15, 2021 - Art. 4: “The President of the court may, at the request of a debtor, appoint an ad hoc agent whose mission he shall determine. The debtor may propose the name of an ad hoc agent. The decision appointing the ad hoc agent shall be communicated for information to the statutory auditors when they have been appointed. The competent court is the commercial court if the debtor carries on a commercial or craft activity, and the judicial court in other cases. The debtor is not required to inform the social and economic committee of the appointment of an ad hoc agent”.

[24] According to Article 550 of the Moroccan Commercial Code.

[25] Ibid., Article 549.

[26] Article 550 of the Moroccan Commercial Code.

* From the terminology of the third paragraph of Article 549 of the Moroccan Commercial Code, “The president of the court shall appoint the special agent... upon the proposal of the head of the undertaking...”, it is understood that the appointment is linked to the proposal. This is especially so as the Code has bypassed the issue of the extent to which the opinion of the court president and the head of the undertaking on the person of the special agent may align or conflict. Conversely, the failure to address the issue may be an oversight by the Moroccan legislator.

[27] Shamaia, A. (2018). *Sharh Ahkam Nizam Mu’alajat Sa’ubat al-Muqawala fi Daw’ al-Qanun 17-73* [Explanation of the Provisions of the System for Handling Undertaking Difficulties in Light of Law 17-73]. Dar Al-Afaq Al-Maghribia, p. 65.

[28] R600-2, C. Com, Fr.

[29] Schwartz, M. G. (2013). The concept of the ad hoc mandate. Doctoral thesis, University of Poitiers, pp. 220-221.

* Nevertheless, the court’s President may not appoint a special agent whose appointment has not been proposed by the debtor enterprise without first obtaining the latter’s consent to the terms of their fees or remuneration, based on the second paragraph of Article R611-47-1 of the French Commercial Code.

* This appears to be a typo in the source text. The provision for appeal is in Article R611-20 of the French Commercial Code.

[30] Balemaken, E. L. R. (2013). The judge and the rescue of businesses in difficulty in OHADA law and French law: A comparative study. Doctoral thesis, Université Panthéon-Assas, p. 79.

[31] Schwartz, M. G. (2013). The concept of the ad hoc mandate. Doctoral thesis, University of Poitiers, pp. 200-201.

* It should be noted that in the case where the debtor enterprise is a sole proprietorship with limited liability or a self-employed entrepreneur under the conditions specified in Section 3 of Chapter VI of Title II of Book V of the French Commercial Code, the assessment of the existence of remuneration or payments received by the person from the debtor enterprise is made with respect to all the assets held by the latter, not limited to the assets allocated to the specific activity, based on the first paragraph of Article L611-13 of the French Commercial Code.

[32] Article L 233-16 of the French Commercial Code provides for two types of control: exclusive control and joint control. The first is achieved in the following cases: 1° When the controlling company holds, directly or indirectly, a majority of the voting rights in another company called the subsidiary; 2° When the controlling company has appointed the majority of the members of the administrative, management, or supervisory bodies of another company for two consecutive financial years, considering that the controlling company holds, directly or indirectly, a portion exceeding 40 percent of the voting rights, and no other partner or shareholder holds, directly or indirectly, a larger portion; 3° When the subsidiary has the right to exercise a decisive influence over a project under a contract or statutory provisions permitted by applicable law. Joint control is achieved when control over jointly managed projects is shared with a limited number of partners or shareholders, such that decisions result from their agreement.

* This is a procedure that helps to prevent debtor enterprises from bankruptcy in general through a rescue plan prepared and presented by the enterprise’s management, the enrichment and supervision of which is handled by a professional appointed by the competent judicial authorities.

* This is a collective procedure that opens a consultation between the competent court and the representatives of the enterprise in cessation of payments, under the supervision of the public prosecutor’s office and the employees, with the aim of preserving the enterprise’s continuity.

* A consular judge (juge consulaire) is the name given to merchants, artisans, or service providers elected for a term of two or four years to sit alongside professional judges in French courts, including commercial courts.

[33] R611-20, C. Com, Fr.

[34] Third paragraph of Article 459 and Article 550 of the Moroccan Commercial Code.

[35] Schwartz, M. G. (2013). The concept of the ad hoc mandate. Doctoral thesis, University of Poitiers, p. 240.

[36] Delebecque, P., Germain, M. (2011). Comprehensive Commercial Law: Commercial Instruments, Banks and Stock Exchanges, Commercial Contracts, Collective Proceedings (Part II; A. Moukalled, Trans.). University Establishment for Studies, Publishing and Distribution, p. 1214.

[37] Saint-Alary-Houin, C. (2020). Law of businesses in difficulty (12th ed.). LGDJ, Domat., p. 192.

[38] Schwartz, M. G. (2013). The concept of the ad hoc mandate. Doctoral thesis, University of Poitiers, p. 80.

[39] Last paragraph of Article 550 of the Moroccan Commercial Code. While there is no corresponding article in the French Commercial Code, this is reflected in actual practice.

[40] Marie Goncalves Schwartz, op. Cit, p. 241.

* The President of the court can deduce from the periodic reports submitted to him by the special agent.

[41] R611-21, C. Com, Fr.

* The same applies to a conciliator, as they are subject to the same provisions governing their fees or remuneration.

[42] Koehl, M. (2019). Negotiation in the law of businesses in difficulty. Doctoral thesis, Université Paris, p. 75.

[43] R611-47, C. Com, Fr.

* The court clerk notifies the order setting the fees to the special agent and the debtor enterprise. He also immediately notifies the public prosecutor if conciliation is used to determine the fees. It can be appealed by the special agent or the debtor before the first president of the Court of Appeal, noting that the appeal is submitted and heard within the time limits and conditions provided for in Articles 714 to 718 of the French Code of Civil Procedure, based on Article R611-50 of the French Commercial Code.

* Because the President of the court works to inform the public prosecutor to give their opinion, suppose the public prosecutor does not give their opinion. In that case, the President of the court cannot open the special mandate procedure before the expiration of forty-eight hours from the date of notification, according to the third paragraph of Article R611-47-1 of the French Commercial Code.

[44] R611-48, C. Com, Fr.

[45] Ibid., R611-49.

[46] Ibid., L611-14, para. 01.

[47] Bouquet, B. (2008, January/February). Ad hoc mandate and conciliation: a renovated legal tool. R J C, (1), 4.

[48] L611-15, C. Com, Fr.

[49] Last paragraph of Article 549 of the Moroccan Commercial Code.

[50] Schwartz, M. G. (2013). The concept of the ad hoc mandate. Doctoral thesis, University of Poitiers, p. 287).

* A judgment from the Court of Appeal of Grenoble in France supports this. In summary, to enable a group of companies preparing for a major acquisition, a consortium of banks met to finance the operation. The group of companies experienced financial difficulties, particularly with its cash flow, and consequently requested a renegotiation of its loan repayment schedule. Subsequently, the group faced further financial difficulties, leading two subsidiary companies to request the benefit of a special mandate in September 2006 to assist in their negotiations with the banking consortium for the renegotiation of the previously agreed loan schedule. This resulted in the opening of a conciliation procedure, and an agreement was subsequently approved in February 2007. The group experienced new financial difficulties in the first half of 2007, and a second conciliation was conducted in July 2007 to find new investors. A conciliation protocol was established in November 2007, providing for several restructuring and loan rescheduling operations. Despite this continued banking support, the statutory auditor, in July 2008, informed the shareholders—in application of the duty to alert—of facts likely to compromise the continuity of operations. Faced with this growing deterioration, the group’s companies requested the appointment of a new conciliator in September 2008. Two meetings were held between the banking consortium and the concerned companies, which failed to inform the consortium about the alert procedures and the appointment of the conciliator. However, one of the banks discovered the existence of the auditor’s alert procedures and the opening of the conciliation procedure, and decided to terminate the contractual relationship in October 2008, based on the failure to be informed about the alert procedures and the conciliator’s appointment. In response, the group’s companies declared a cessation of payments, and judicial settlement proceedings were opened against them in November 2008, leading to their liquidation through a sale plan in March 2009. The liquidator subsequently filed a claim for damages against the bank that cut off the credit facilities. The Commercial Court of Grenoble issued a judgment on January 10, 2010, ordering the bank to pay. However, the appellate judgment overturned this, considering the managers’ conduct to be disloyal because they did not inform the banking consortium that their companies were subject to alert and conciliation procedures. For more details on the judgment, see: Court of Cassation, Commercial Chamber. (2012, February 7). Judgment No. 10-28.815, 10-28.816] [Unpublished]. <www.legifrance.gouv.fr/juri/id/JURITEXT00002535783>.

51 Schwartz, M. G. (2013). The concept of the ad hoc mandate. Doctoral thesis, University of Poitiers, pp. 290-293.

* These provisions mainly regulate the independence of the special agent and the criteria for determining their fee, as previously discussed.

* The mission of the conciliator generally consists of mediating between the debtor enterprise and its creditors to bring their views closer together, in the hope of resolving the difficulties facing the debtor enterprise and achieving the required continuity. This is primarily found in Article L 611-7 of the French Commercial Code and Article 554 of the Moroccan Commercial Code.

[52] European Commission. (2022). Insolvency Frameworks across the EU: Challenges after COVID-19 (Discussion Paper 182).

Downloads

Downloads

Published

Issue

Section

License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.