Western Aspirations in Georgia’s Winemaking: Status and Prospects

DOI:

https://doi.org/10.35945/gb.2025.19.003Keywords:

Winemaking, Georgia, tourism, wine exportAbstract

Since its independence from the Soviet Union in 1991, Georgia has sought to revive its wine’s international reputation, diversify wine export destinations, and attract Western wine-loving tourists. Although much still needs to be done to decrease dependence on the Russian market and translate the aspirations into reality, Georgia has progressed in pivoting to the West. The country marketed as the Cradle of Wine has prioritized a Western orientation and holds the prospect of becoming a player in the global wine market. The recommendations provided in this paper are intended to solidify this prospect and break down barriers to entering Western wine and tourism markets. Effective promotion of Georgian wines, the cross-fertilization of wine production and wine and food tourism, and the development of domestic skills and international partnerships should go together with balancing various wine and tourist options. Export diversification should also involve complementing Georgian tradition with innovation, building on Western expertise and funding, and emphasizing premium-level wines, including natural wines.

Keywords: Winemaking, Georgia, tourism, wine export.

Introduction

Georgia – a mountainous country between the Black and Caspian Seas, where Europe meets Asia – is now recognized as a place where wine has been made and celebrated continuously for the last 8000 years.[1] Multidisciplinary international research in archeology, paleoclimatology, chemistry, and biomolecular studies has provided the evidence behind this recognition. It was, however, a Westerner, Hugh Johnson, an English journalist, author, and wine expert, who first referred to Georgia as the Cradle of Wine in his authoritative book Vintage: The Story of Wine.[2]

As Westerners were long fascinated with Georgia and interested in its wines, this paper aims to ascertain Western aspirations in Georgia’s winemaking, historically up to the present day, and to analyze the extent to which these aspirations have so far materialized. The Constitution formalized Georgia’s integration into the Euro-Atlantic networks as the country’s objective. It is, therefore, instructive to test the results of pivoting to the West by the wine and tourism sectors, which are central to Georgia’s economy. Wine is the country’s second most exported commodity.[3] Analysis of respective export data and an assessment of wine and food tourism can give a sense of Georgia’s progress in getting closer to the West. The paper also aims to explore the prospects of wine export diversification away from Russia as a risky traditional destination and provide recommendations for smooth and effective reorientation to the new Western markets. The employed research methods include desk research, analysis of Georgian national and international statistics, and the interviews conducted in May-June 2024 with Westerners working in Georgia’s wine industry, as well as Georgian nationals representing the wine business and government agencies.

This paper builds on the previous research of Georgia’s winemaking in relation to global wine markets and international trade. Comparison of Georgia with traditional wine-exporting countries and the newcomers in the global wine business has led to an exploration of Georgia’s ability to break through and become a viable competitor.[4] In this regard, the work of Kym Anderson, an Australian economist who specializes in trade policy, is especially relevant to our analysis.[5] Given the attractiveness of the United States (US) large and prosperous consumer market, assessments of the prospects for Georgian wines to enter it and develop a favorable position are also of specific interest.[6]

Analysis squarely focused on Georgia’s wine industry revealed its strengths, successes, and potential, suggesting its possible attractiveness to Western investors and producers.[7] As Georgia’s appeal calls for effective marketing of wine, the literature on this topic further informs the chances of the Western orientation of Georgian winemaking and wine exports. For example, it was demonstrated that storytelling as a marketing vehicle, including branding Georgia as the Cradle of Wine, can open new markets by linking the entrepreneurial process to Georgian culture.[8] Bridging winemaking with food and wine tourism was shown to be another strategic marketing tool for Georgia.[9] Vice versa, public relations tips on how to penetrate the Georgian market offered help to Westerners seeking business in Georgia. On a more general note, the exploration of the intersection of wine, society, and business in Georgia enriched the understanding of the national context as well as the influence of geopolitics on Georgia’s interactions with Russia and the West.[10]

The paper is organized into six sections. Following the introduction, the second section traces Georgia’s Western aspirations from the international fame of the country’s 19th-century winemaking, through the post-Soviet revitalization of the wine industry, to the present-day targeting of Western markets, accounting for support from Western and international organizations. Russia’s 2006-2012 embargo on Georgian wine and the influence of the Russia-Ukraine war since 2022 are discussed as periods of the swings in Georgia’s trade flows that reinforce the need for wine export diversification. The third section addresses the challenges and opportunities of such diversification. It reveals Georgia’s persistent dependence on Russian demand for its wine. In contrast, it connects the opportunities for diversification away from Russia with the increase of Georgian wine exports to the US and the European Union (EU). The linkages between Georgia’s unique wine culture and wine and food tourism are the theme of the fourth section. Based on the interviews with Westerners working in Georgia’s wine business, the fifth section reports their assessments of the wine industry’s status and prospects. The concluding sixth section focuses on recommendations.

Past and Present

From the 19th-Century Fame to the Post-Soviet Reconstruction

Westerners’ interest in Georgian winemaking traditions and their involvement in the country’s wine industry have roots in the 19th century. Prince Alexander Chavchavadze (1786-1846), a poet, Lieutenant-General, and businessman, introduced Western winemaking technology at his hereditary Tsinandali estate, thus contributing to Georgian wine’s fame in Europe (Prince, 2024). Prince Ivane Bagrationi-Mukhranbatoni (1811-1895) launched a “golden age” of Georgian winemaking by employing a French agronomist, importing the best foreign machinery and tools, and establishing an efficient European-style farm in his estate not far from Georgia’s capital Tbilisi.[11] Mukhranbatoni’s smart integration of Georgian traditions and Western innovation paid off. His “Mukhranuli” brand won a gold medal at the 1889 Paris Exposition Universelle.[12]

During the first modern wave of globalization in the 19th century, Georgia managed to supply wines not only to the Russian Empire (to St. Petersburg, Moscow, Warsaw, and the Baltic nations), including the Russian imperial court, but also to Western Europe. Georgian wines received wide international recognition in European capitals, such as Paris and Vienna.[13]

In the Soviet period (1921-91), Georgia found itself cut off from international markets and Western technologies and expertise. But following its independence in 1991, the country welcomed international investment and Western winemaking mastery. As an example, the Tsinandali complex associated with the name of Prince Chavchavadze has been, since 2008, under the patronage of the Silk Road Group, which is owned and run by Georgian and European partners.[14] The restoration of the decrepit palace and farm of Prince Mukhranbatoni led to the creation in 2010 of the joint-stock company Château Mukhrani, now owned by the Swedish businessman and founder of the Marussia Beverages Group, Frederick Paulsen.[15]

Russia’s Wine Embargo as a Stimulus for Export Diversification

Russo-Georgian post-Soviet relations have been marked by hostility and distrust, mostly caused by Russia’s support of the secessionist regions of Abkhazia and South Ossetia. In this atmosphere, in 2006, the Russian government introduced an embargo on Georgian wine under the pretext of its low safety and quality standards. Considering that Russia accounted at that time for 80 percent of Georgian wine exports, the losses from this embargo were extensive. Whereas the share of Georgia’s wine production volume that was exported grew rapidly between 2000-2005 to nearly 50 percent, it collapsed to just 7 percent by 2007.[16]

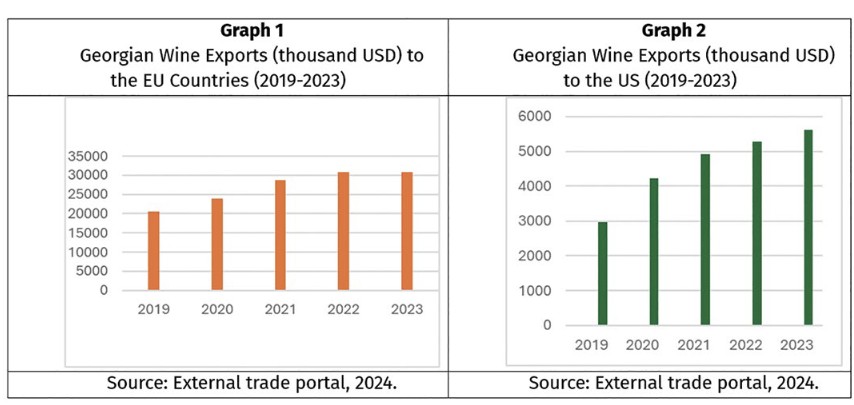

Trading with the West—the European countries and the US—became Georgia’s primary objective in the post-Soviet period, especially during the years of Russia’s wine embargo. There are some achievements in this area. Georgia’s wine exports to the EU countries surged threefold during the decade of 2009-2018, have been expanding since then, and reached $31 million in 2023 (Graph 1). Similarly, Georgia’s wine exports to the US experienced significant growth. They increased 1.5 times from 2009 to 2018 and totaled $5.6 million in 2023 (Graph 2).

Western Support for Winemaking in Georgia

Western institutions are at the forefront of revitalizing Georgia’s winemaking. The USAID/Georgia’s Economic Security Program, implemented since 2006, has helped the Georgian government with the export of wine to the West, especially the US, and wine-related tourism. In partnership with the Wine Association of Georgia and the Wine Club, USAID supported multiple wineries to enable their readiness to accept tourists and trained wine guides.[17] USAID also partnered with the Georgian Orthodox Church and Badagoni Winery to create the Alaverdi Heritage Trail to increase international tourism.[18]

Within the theme of “Unlocking Potential for Georgian Wine in US Markets”, the USAID Agriculture Program has supported small and medium-sized winemaking enterprises in terms of marketing and export. In collaboration with the US-based crowdsourced insights company Premise, USAID explored market trends and consumer preferences from three US markets: California, New York City, and Washington, D.C.[19] It also offered export grants and provided funding for wine degustation and trade missions, and fairs.

Likewise, multilateral international organizations have entered Georgia’s wine scene. The World Bank’s Regional Development Project for Georgia has worked to improve infrastructure services and institutional capacity to support the development of a tourism-based economy and cultural heritage circuits in the winemaking Kakheti region. The World Bank has also sought to enhance the institutional capacity and performance of national institutions, such as the Georgia National Tourism Administration (GNTA) and the Agency for Culture Heritage Preservation of Georgia (ACHP).[20] Furthermore, the United Nations’ Food and Agriculture Organisation’s (FAO) “Inclusive Rural Development and Sustainable Agriculture” project has benefited winemaking among other agricultural segments.[21]

The international efforts are in tune with the priority of the National Wine Agency (NWA) of Georgia, which is to market Georgian wines to the West, especially European countries and the US. The NWA organizes international exhibitions and presentations of wine, wine festivals, and the International Qvevri Competition, promoting the ancient Georgian method of using terra cotta urns buried in the ground for fermenting crushed grapes. It also participates in wine expos and fairs, supports exchanges among wine professionals across the world, and holds Ghvino (ღVino) Forums of America in collaboration with the America Georgia Business Council.[22]

Russia-Ukraine War and its Implications for Georgia’s Wine Exports

Following the onset of the Russia-Ukraine war in February 2022, Georgia’s economic dependence on Russia increased compared to previous years. In 2022, about 15 thousand Russian companies were registered in Georgia, 16 times more than the number in 2021. Georgian exports to Russia increased by 6.8%, and imports from Russia rose by 79%.[23] A recovery in tourism and a surge in immigration, financial inflows, and transit trade triggered by the war have boosted GDP growth and fiscal revenues. Although financial inflows sparked by the war have recently moderated, by early 2024, they remained above prewar levels, supporting a positive macroeconomic outlook.[24]

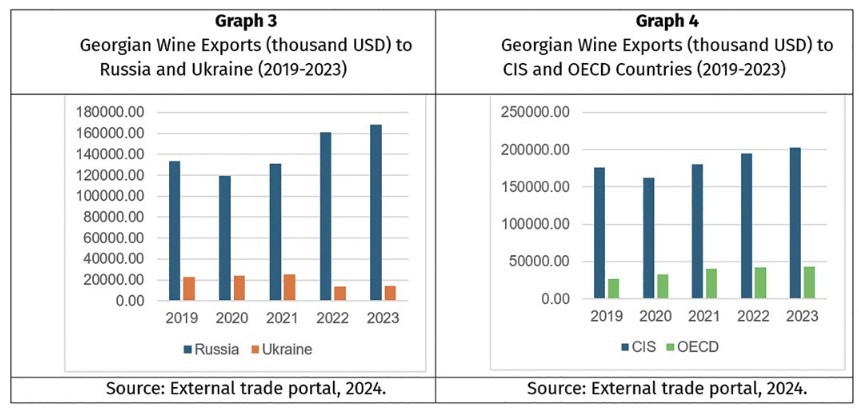

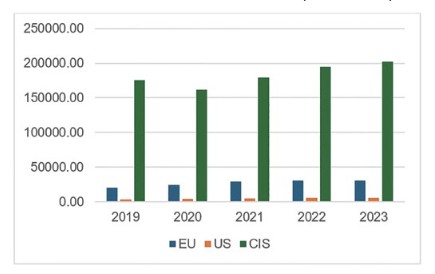

Under these war-related economic conditions, Georgia’s dependence on the Russian market in terms of wine exports intensified.[25] In 2023, wine ranked first in the exports of Georgian goods to the Russian market, amounting to $168 million[26] and constituting a 29% increase from 2021. In contrast, wine exports to Ukraine declined by 42% in 2023, compared to 2021, and totaled $14 thousand, or 12 times less than respective exports to Russia (Graph 3). During the same period of 2021-2023, Georgian wine exports to the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS), countries of the former Soviet Union that include Russia and its allies, increased by 13% and reached $203 million in value. The same exports to the member states of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), which is dominated by Western countries, increased by only 5% and reached the $43 million mark in 2023, which is four times less than exports to the CIS (Graph 4).

Challenges and Opportunities of Wine Export Diversification

Challenges

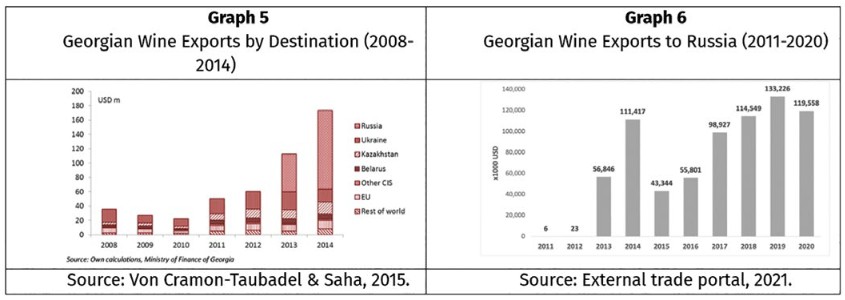

According to a study conducted by the German Economic Team Georgia and ISET-PI, during the years of the Russian embargo (2006-2012), demand for Georgian wine in the EU and non-CIS countries was not able to replace the Russian market (Graph 5).[27] Some observers argued that the Russian embargo was a blessing rather than a curse for Georgia’s winemaking as it stimulated improvement in the quality of wine and diversification of the country’s exports. Most producers were, however, happy to see the ban lifted, which made wine exports to Russia rise substantially (Graph 6). Upon the end of the embargo in 2013, Georgia’s exports to Russia skyrocketed to an amount worth more than $111 million in 2014.[28]

The same happened as a result of the Russia-Ukraine war, which propelled Georgia’s wine exports to Russia to an unprecedented value of $168 million.[29] Exports to the EU and US continue to be dwarfed by those to the CIS countries (Graph 7). Within the CIS, Russia remains the major importer of Georgian wines, up to 83% in 2023. Russia’s imports amounted to 60% of Georgia’s total wine exports in 2018 and increased to 65% in 2023, the highest figure since 2005.[30]

Graph 7

Georgian Wine Exports (thousand USD) to the CIS Countries Compared to Exports to the EU and US (2019-2023)

Source: External trade portal, 2024.

The current export statistics suggest that much is still to be done to diversify Georgia’s wine exports away from Russia. Neighboring Russia is Georgia’s traditional market. This explains its large share of Georgia’s exports. The external circumstances have contributed to maintaining and even enlarging this share, compared to the previous years.

Yet, Georgia’s wine exports no longer face an 80% dependence on the Russian market as before Russia’s wine embargo, and the developments since then have shown that the export quantity can be detrimental to wine quality. Therefore, entry into high-value Western markets with high-quality goods and products has been pushed to the top of Georgia’s agenda, which calls for increasing awareness of Georgian wines, reducing entry costs to new markets, and aligning the supply of particular wines with demand.

Opportunities

The swings in Georgia’s trade flows due to outside factors and difficulties in reorienting the country’s commerce toward the West do not mean that diversification of wine exports is a lost cause. The 2006-2012 embargo period remains a sore reminder of the urgency of strengthening trade relations with other countries, especially those in the West. At the same time, revenue from sales on the Russian market after the end of the embargo allowed for continuing improvements in Georgia’s wine industry.[31] The effect of the Russia-Ukraine war on Georgia’s economy has been waning, and although the high dependence of wine exports on the Russian market persists, the end of the war can bring changes.

Prioritizing the US in Wine Export Diversification

With support from Georgian government agencies and international organizations, the wine industry is pushing forward. Georgia attributes the utmost importance to the US as the two countries signed the US-Georgia Charter on Strategic Partnership (2009) and reaffirmed the Charter’s principles on its 10th anniversary (2019). Georgia and the US also signed a bilateral investment treaty and a bilateral trade and investment framework agreement.[32]

There are also specific wine-related reasons for targeting the US market. The US tops the list of countries whose population drinks the most wine in terms of total volume, accounting for around 15% of the world’s total wine consumption.[33] According to Tamta Kvelaidze, Head of the Marketing & PR Department at the NWA, the agency prioritizes marketing Georgian wines to the US as the world’s largest wine consumer. The NWA has contractors in all markets; in the US, it is Colangelo & Partners, an integrated communications agency specializing in food, wine, and spirits, with offices in New York City and San Francisco.[34] The Teliani Valley company[35] one of Georgia’s largest wine producers, opened its office in the US, established its own distribution company and warehouse in California, and launched an extensive marketing campaign. If successful, Teliani Valley’s strategy can be replicated by other winemakers in Georgia.[36]

Since 2013, the US market for Georgian wines has been one of the fastest growing and showed an almost eightfold increase in dollar terms and nearly sixfold expansion in volume.[37] Cooperation between Georgian and US wineries and educational visits to Georgia by members of the US Wine Lovers Club have sought to support this upward trajectory by raising awareness of Georgian wine.[38]

To accurately assess the status and potential of Georgia’s exports to the US, different segments of the wine market should be considered. The recent worldwide trend, which is expected to continue, is “premiumization – the demise of non-premium wine and the emergence of commercial premium wine”. The volume of consumption of fine and commercial premium wines was projected to be about one-sixth higher, and the volume of non-premium wine slightly lower in 2025 than in 2016–2018.[39]

The US market, one of the most affluent consumer markets, is deemed to be a high-value one for Georgian wine because of the comparatively high prices.[40] According to Zurab Mgvdliashvili, a co-founder of the Natural Wine Association of Georgia, the US is an almost single importer of the premium-segment natural wines produced by the 120 members of his association. Whereas in 2023, the overall annual export of Georgian wines reached 89.5 million liters or almost 120 million bottles,[41] the country’s export of natural wines counts in a couple of thousand bottles. Yet, the latter export can be more lucrative as a bottle of natural wine is four times more expensive than an average bottle.[42]

Market research has revealed the following key obstacles faced by Georgian wine exporters in the US: high logistics costs, complex US legislation, limited awareness of Georgian wine, and copyright issues.[43] These are serious barriers, but they are not insurmountable. Julie A. Peterson, Managing Partner at the Marq Wine Group and a former NWA contractor, underscored and celebrated the impressive growth of Georgian wine exports to the US. “The challenge is to sustain this growth; the key is to keep traction”, advised Ms. Peterson.[44]

Expanding to the EU

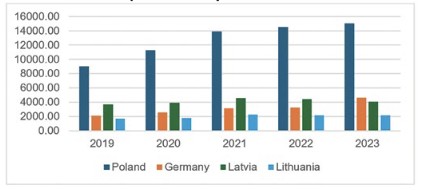

In 2014, Georgia and the EU signed an Association Agreement, which included the Deep and Comprehensive Free Trade Agreement (DCFTA), allowing Georgian products to enter the EU market without customs duty.[45] The top importers of Georgian wine among EU members in 2023 were Poland, Germany, Latvia, and Lithuania (Graph 8). Poland consistently played a leading role: in 2023, it accounted for 49% of Georgian wine exports to the EU and was the second-top importer of Georgian wine in the world, although its 6% share was much smaller than the 65% share of Russia. In 2023, Germany overtook Latvia as the #2 EU importer of Georgian wine.[46]

Graph 8

Top Importers of Georgian Wine (thousand USD) among EU Member Countries (2019-2023)

Source: External trade portal, 2024.

The NWA places Germany and Poland as the best candidates after the US for extensive marketing and export diversification.[47] According to the 2023 data, Germany was fourth in the world among countries whose population drinks the most wine and was the fifth in per capita wine consumption.[48] At the same time, Germany was ranked as the eighth-largest producer of wine in 2023.[49] Although France and Italy are top wine consumers after the US, Georgia hardly exports its wine to these countries, ranked in 2023 as first and second wine producers.[50] In contrast, Poland, which is known for vodka and beer but not wine, is a promising importer.

Wine Culture as a Driver of Tourism

Georgia is not only a wine country. It is also a land of exceptional natural beauty, a long and unique history, and an extraordinary landscape and ecological diversity. All these characteristics are attractive for tourism, but Georgia’s wine culture has emerged as the country’s leading promoter. “Tasting local cuisine and wine” was one of the most popular tourist activities, the second only after shopping, in 2022.[51] In 2023, it became the top activity, as 78.1% of international visitors cited it.[52] In 2022, the added value of Georgia’s tourism-related industries as a share of GDP increased from 6.7% to 7.2%. More than 20% of this value was driven by food and beverage services.[53]

Tourism offers an opportunity to sell wine directly to consumers in wineries and plays a critical role in the advancement of local communities. Many rural producers in Georgia do not have distribution contracts enabling them to retail their wine. Therefore, the openness of their establishments for visitation, which typically includes tours, tastings, and opportunities to purchase beverages, is indispensable.[54]

Similar to winemaking, tourism can generate secondary economic activity. Accounting for its effect on other sectors of the economy, it was estimated that in 2018, before the COVID-19 pandemic, 31.3% of Georgia’s GDP depended on the travel and tourism industry, including parks and transportation.[55] On average, tourism’s direct and indirect contribution to Georgia’s total economy is more than 25%, whereas this figure for the global economy is only about 7.5%.[56]

Advertising Georgia as the Cradle of Wine and wine as a symbol of Georgian national identity has naturally connected wine production with wine and food tourism, and wine culture has become one of the drivers of global awareness of and interest in Georgia. In 2023, 7.1 million international travelers visited Georgia, and the country received a record $4.1 billion in tourism revenue.[57]

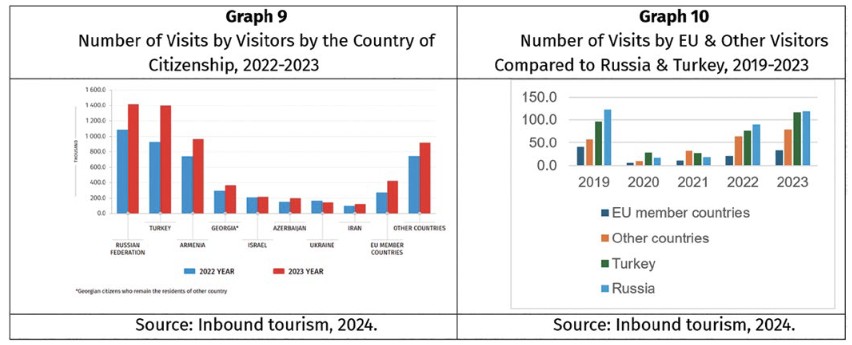

The largest number of visitors (1.2 million) in 2023 was from Russia, amounting to 23.2% of the total number of visitors, followed by Turkey (21.4%) and Armenia (13.5%). Correspondingly, the citizens of Russia, Turkey, and Armenia made the most visits (Graph 9).[58]

As is seen in Graph 10, compared to the largest shares of visits to Georgia from Russia and Turkey, the number of visits from the EU member countries has been small and has not yet returned to the pre-pandemic level. As for visits from “other countries”, a category that includes the US, their number has exceeded the pre-pandemic level in 2022 and increased further in 2023. The proportion of visits by EU visitors in the total number of visits to Georgia was 6% in 2023.[59]

The International Visitor Surveys conducted by the GNTA at airport or land border checkpoints offer more detailed data. It turns out that both before the COVID-19 pandemic in 2019 and recently in 2023, Western visitors stayed substantially longer in Georgia than those from Turkey. For example, the average length of stay of US citizens was 10 nights in 2023, compared to 1.9 nights for visitors from Turkey. At the same time, US visitors stand out as higher spenders. Their average expenditures were almost twice as high in 2023 as spending by visitors from Poland and France.[60] Considering that a large share of visitors’ expenditures is consistently registered on served food and drinks, spending on wine consumption significantly increases the proceeds of tourism to Georgia.[61]

These data reiterate the point about the difference between high-value and low-value economic activity. As Georgian wine exporters target markets in the US and other Western countries, the country’s tourist organizations are especially interested in visitors from these countries because of the expectations of higher returns. International tourism helps the Georgian wine sector and vice versa. Visitors touring wineries and buying directly from sellers drive higher demand for Georgian wine delivered to their home countries. Conversely, increased awareness of Georgian wine attracts more wine enthusiasts to visit the country.

Westerners in Georgia’s Wine Business: Assessment of Industry’s Status and Prospects

Looking beyond statistical data, the interviews conducted in May-June 2024 with Westerners working in Georgia’s wine industry revealed a buoyant mood about the country’s prospects in the global wine market.[62] “Georgia is extremely exceptional: it has a perfect story – amazing history, tradition, sustainable farming, and also good wines, including the natural ones”, stated Julie A. Peterson, a US consultant. This positive assessment was shared by Patrick Honnef, the Germany-born CEO of Château Mukhrani, who referred to a “renaissance of Georgian wine culture”: “Ten years ago, there was no wine agency, no national tourist administration, and no wine associations. Now there is a young generation that is better educated, the quality of wine is improving, and overall, it is a thrilling time”.

Olivier Sauvage, a French businessman and consultant, agreed that “winemaking in Georgia has potential”, but also pointed to the challenges: the predominance of semi-sweet wines in Georgian exports, which are not favored by younger generations, and the lack of professionalism compared to the international level. He also highlighted the relatively high price of Georgian mass-produced wines, compared to the prices of international competitors, such as Spain or Chile. The reason behind the high price is small-scale production in Georgia and the large costs of supplies and logistics. Both Mr. Sauvage and Mr. Honnef also pointed to the constraints of land legislation, which allows foreigners to buy land only in cooperation with Georgian residents and thus limits the scale of wine production. The lack of foreign investment is another barrier.

The question is what’s to be done to ensure further progress. “Wine is the number one value export of Georgia, it can transform the Georgian economy”, said Ms. Peterson, referring to the benefits of entering the US market with its 19 million consumers of wine. Georgian wines are sold on average for $5.15 a bottle in the US market and only for $2 a bottle in Russia; some wineries can sell for $9-$11 a bottle.

As for skills, Mr. Honnef values his young Georgian staff hired fresh from the Agricultural University and the Technical University in Tbilisi, and also sees promise in interns attracted to work with him. There are study-abroad programs supported by universities, the EU, and USAID, which open opportunities, but more investment in travel, training, and international partnerships is needed.

Georgia is proud of its winemaking tradition, but tradition must be balanced with and reinforced by international expertise. “Georgians need to learn, need innovation,” underscored Mr. Sauvage. Mr. Honnef was upbeat in this regard: “Today the new generation understands the global market and competition from abroad and seeks higher wine quality and new markets. Progress comes with open-mindedness and innovation”.

Prioritizing Western markets means an increasing emphasis on premium-level wines. According to Ms. Peterson, “Georgia needs to make exceptional wines and to align the types of wines with trends in wine consumption”. Mr. Honnef agreed with the preferred focus of Georgia on premium-level wines but advocated gradual diversification of the types of wines (contingent on demand) and steady development of new markets, such as the US and Germany, while maintaining the traditional ones. Pivoting to the West – both in terms of wine exports and wine and food tourism – should offer increasing financial returns. It can also have a political impact. But as Georgia is determined to strengthen its international outreach, shifts should not be abrupt.

“Georgia must stay on course but adjust every year. Marketing must be integrated with building logistics, skills, distribution, and sales – all components must work together. This country has all the ingredients for success and demonstrated progress; it just needs to stay the course, not slow the way forward”, emphasized Ms. Peterson.

Conclusion

Based on the findings of desk research and assessments, and suggestions of the interviewed Georgians and Western experts, the following conclusions and recommendations can be made.

- The wine industry is a priority sector of Georgia’s economy. Wine was the second most exported commodity in Georgia in both 2023 and the first half of 2024.[63] The rank of wine in Georgia’s exports has increased compared to 2018, when the wine industry was the fifth-largest export generator for the country.[64] The share of wine exports in Georgia’s GDP has been growing along with the GDP growth,[65] and the wine industry provides a multiplier effect on the economy as it is closely linked with its major sectors. Hence, mastering Western markets is worth pursuing, as every expansion of Georgian exports to the West is not merely a source of revenue but an engine of economic growth and social development.

- Effective marketing is imperative for positioning Georgian wines in the Western markets. As storytelling is an important marketing vehicle, Georgia’s story as the Cradle of Wine combines history and tradition and suggests continuity through sustainable farming. As “tasting local cuisine and wine” is one of the most popular tourist activities in Georgia, the cross-fertilization of wine production and wine and food tourism is beneficial for the national economy and global awareness of the country. Marketing should not, however, stand alone; it must be integrated into the entire system of wine production, tourism management, and skills development. It should also constantly improve, building on the successes of international partnerships and marketing campaigns and learning lessons from the operation of offices and distribution companies abroad.

- There is a consensus about the need to develop wine export markets beyond Russia and decrease dependence on Russia. However, the benefits of maintaining exports to Russia are also recognized. The same applies to balancing various tourist markets. Although pivoting to the West is expected to offer both economic and political advantages to Georgia, shifts in export and tourism strategies should be well-prepared and measured. Gradual diversification of the types of wines and steady development of new Western markets, such as the US and Germany, should go together with preserving the traditional ones. This gradual strategy is most feasible and beneficial.

- Georgian wine exporters face serious barriers in the West, ranging from high logistics costs to copyright issues and a mismatch between the types of wines produced and the global demand. Georgian mass-produced wines are also expensive, compared to the prices of international competitors, because of Georgia’s small scale of grape cultivation, the high costs of supplies, the constraints of land legislation, and the lack of foreign investment. To break down these barriers, it is crucial to complement Georgian tradition with innovation and to inject Western expertise and funding, both via private ventures and state and international assistance. To make Georgian wines viable in the global market, enhanced professionalism of winemakers, higher wine quality, and aligning the types of exported wines with wine consumption trends are essential.

- Given the characteristics of Georgia’s agriculture and winemaking, the country can hold a prominent position in niche markets in the world. As the recent worldwide trend is “premiumization”, Georgia is well-positioned to emphasize premium-level wines, including natural wines, in its production and exports. The US and Germany are the best among affluent high-value markets for the premiumization of Georgian exports and a focus on natural wines. In choosing major targets for export diversification, the recipient countries’ per-capita consumption of wine, the volume of their wine production, and the relative competitiveness of their wine industries should be considered. Similarly, attracting high-value tourists from the US and Germany can yield higher returns, including through visitors’ expenditures on wine.

Bibliography:

- ge. (2024, April 26). Georgia, FAO sign new $4m project to boost sustainable agriculture, rural development. Available at: https://agenda.ge/en/news/2024/38857#gsc.tab=0;

- Anderson, K. (2009). Wine’s New World. Foreign Policy. Available at: https://foreignpolicy.com/2009/11/02/wines-new-world/;

- Anderson, K. (2012). Rural development in Georgia: what role for wine export growth? Wine Economics Research Centre Working Paper, 0112;

- Anderson, K. (2020). Is Georgia the next ‘new’ wine-exporting country? Chapter 13 in The international economics of wine. World Scientific Studies in International Economics, 73;

- Anderson, K., Pinilla, V. (2021). Wine’s belated globalization, 1845–2025. AAEA Agricultural & Applied Economics Association – Wiley;

- Buckley, N. (2013, February 4). Georgian wine to flow as Russia lifts ban. Financial Times. Available at: https://www.ft.com/content/13269432-6ee9-11e2-9ded-00144feab49a;

- Colangelo & Partners (2024). Available at: https://www.colangelopr.com/;

- Dinello, N. (2022). Centrality of winemaking in Georgia: from prehistoric age to present-day globalization. Journal of Wine Research, 33(3);

- Enterprise Georgia. (2024). Free trade regimes;

- Extension - University of Georgia. (2024). Georgia’s Alcoholic Beverage Industry 2024 Outlook;

- Gambashidze, D. (2023, July 31). Georgian wine is gearing up to strengthen its position in the US market. Forbes;

- Georgian Journal. (2021, September 23). Georgian wine eyes USA market. Available at: http://georgianamerica.com/eng/news/georgian_wine_eyes_usa_market_2744;

- Georgian National Tourism Administration. (2023). Georgian tourism in figures: structure and industry data 2022. Available at: https://gnta.ge/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/2022-eng-1.pdf;

- Georgian National Tourism Administration. (2024). Conducted Activities. International Visitors Survey. Available at: https://gnta.ge/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/International-Visitor-Survey-2023.xlsx;

- Georgia National Tourism Administration. (2024). International visitor survey 2015-2023. Available at: https://gnta.ge/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/International-Visitor-Survey-2023.xlsx;

- Georgia National Tourism Administration. (2024, February 12). Record $4.1 billion in tourism revenue and 7.1 million international travelers - 2023 statistics;

- Gelashvili, A. (2024). The Revived Legend of Mukhrani. Sandro Books Publishing;

- Granik, L. (2019, July 29). Understanding the Georgian wine boom. Seven Fifty Daily. Available at: https://daily.sevenfifty.com/understanding-the-georgian-wine-boom/;

- IMF Country Report No. 24/135. (2024, May). Georgia: 2024 article IV consultation—press release, staff report, and statement by the executive director for Georgia;

- International Business Development and Investment Promotion Center. (2014, December 20). Marketing research of wine tourism sector in Georgia;

- Interviews with Honnef, P. (2024, May 24), Mgvdliashvili, Z. (2024, June 7), Kvelaidze, T. (2024, June 3), Peterson, J. (2024, June 5), & Sauvage, O. (2024, May 5);

- Jmukhadze, N. (2022. August 1). The role and influence of wine export on the economic growth of Georgia. Forbes. Available at: https://forbes.ge/en/ghvinis-eqsportis-roli-da-gavlena-saqarthvelos-ekonomikur-zrdaze/;

- LEPL National Wine Agency. (2024). Available at: https://wine.gov.ge/En/Page/mainactivities;

- Lordkipanidze, D. (ed.). (2017). Georgia the cradle of viticulture. National Geographic Magazine - Georgia in collaboration with the Georgian National Museum. Available at: https://nationalgeographic.ge/story/georgia-the-cradle-of-viticulture/;

- Maghradze, D., et al. (2016). Grape and wine culture in Georgia, the South Caucasus. 39th World Conference of Vine and Wine, BIO Web of Conferences 7 (03027);

- Mercer, C. (2023, May 24). Which countries drink the most wine? Ask Decanter. Decanter. Available at: https://www.decanter.com/wine-news/which-countries-drink-the-most-wine-ask-decanter-456922/;

- National Statistics Office of Georgia. (2021 & 2024). External trade portal. Available at: https://ex-trade.geostat.ge/en;

- National Statistics Office of Georgia. (2024). Exports by commodity groups (HS 2 digit level) in 2015-2024. Export. Available at: https://www.geostat.ge/en/modules/categories/637/export;

- National Statistics Office of Georgia. (2024). Inbound tourism statistics in Georgia. Available at: https://www.geostat.ge/media/59934/Inbound-Tourism-Statistics---%282023-year%29.pdf;

- National Wine Agency of Georgia. (2024, February 9). Export of wine and alcoholic beverages;

- (2024). Price rankings by country of bottle of wine (mid-range) (markets). Available at: https://www.numbeo.com/cost-of-living/country_price_rankings?itemId=14;

- Quinn, C. (2020, April 1). The tourism industry is in trouble. Foreign Policy. Available at: https://foreignpolicy.com/2020/04/01/coronavirus-tourism-industry-worst-hit-countries-infographic/;

- Rytkönen, P., Vigerland L., & Borg, E. (2021). Tales of Georgian wine: storytelling in the Georgian wine industry. Journal of Wine Research, 32(2);

- Shamugia, E. (2023, October 17). Tourism: Georgia and the region. Forbes: Georgia. Available at: https://forbes.ge/en/tourism-georgia-and-the-region/;

- Sharkov, D. (2016, March 3). Russian imports of Georgian wine skyrocket after ban is lifted. Newsweek. Available at: https://www.newsweek.com/russian-imports-georgian-wine-skyrocket-after-lifted-ban-434698;

- Smithsonian in Association with the National Parliamentary Library of Georgia. (2024). Prince Alexandre Chavchavadze (1786-1846). Chavchavadze Family;

- State Department. (2019). 10th Anniversary Joint Declaration on the US – Georgia Strategic Partnership. Washington, DC;

- Teliani Valley. (2024). Available at: https://www.telianivalley.com/en;

- The Embassy of Georgia to the United States of America. (2021). High-level trade dialogue (HLTD). Available at: https://georgiaembassyusa.org/bilateral-trade/;

- Tsereteli, M. (2018, December 7). Georgian wine and its narrative drive development. The Central Asia – Caucasus Analyst. Available at: https://www.cacianalyst.org/publications/analytical-articles/item/13548-georgian-wine-and-its-narrative-drive-development.html;

- Tsereteli, M., Oliker, O., Mankoff, J. (2019, January). Wine, society, and geopolitics. Center for Strategic and International Studies. Available at: https://csis-website-prod.s3.amazonaws.com/s3fs-public/event/190307_Tsereteli_WineSociety_pageproofs5.pdf;

- Tsinandali Estate Museum. (2024). Available at: http://tsinandali.ge/en/museum/about-us;

- Transparency International, Georgia. (2023, February 23). Georgia’s economic dependence on Russia: impact of the Russia-Ukraine war;

- Transparency International, Georgia. (2024, February 16). Georgia’s economic dependence on Russia: summary of 2023;

- United States-Georgia Charter on Strategic Partnership. (2009, January 9). Washington, DC. Available at: https://www.state.gov/united-states-georgia-charter-on-strategic-partnership/;

- USAID Agriculture Program. (2023). Unlocking potential for Georgian wine in US markets. Cultivating New Frontiers in Agriculture (CNFA);

- USAID Economic Security Program. (2023, January 15). Quarterly report. Quarter 1 FY23: October – December 2022. Available at: https://pdf.usaid.gov/pdf_docs/PA02122H.pdf;

- USAID/Georgia’s Economic Security Program: Mid-Term Evaluation (2022, June). Final Report. Available at: https://pdf.usaid.gov/pdf_docs/PA00ZGXC.pdf;

- Von Cramon-Taubadel, S. Saha, D. (2015, May). Short-run risks and long-run challenges for wine production in Georgia. Policy Paper Series, German Economic Team Georgia and ISET Policy Institute, Berlin/Tbilisi;

- World Bank Group. (2012, February 22). Georgia - regional development project;

- World Population Review. (2024). Wine producing countries 2024. Available at: https://worldpopulationreview.com/country-rankings/wine-producing-countries;

- World’s Best Vineyards. (2024). 47 Château Mukhrani, Mukhrani, Georgia;

- Wines of Georgia. (2021). Beyond the niche: the past, present & future of Georgian wine in the US market. Available at: https://winesgeorgia.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/Georgia-301-Virtual-Seminar-26-Aug-2021.pdf;

Zivzivadze, L. Taktakishvili, T. (2019). Index-based analysis of Georgian wine export’s competitiveness on a global market. International Journal of Agricultural Economics, 4(5). Available at: https://sciencepublishinggroup.com/article/10.11648/j.ijae.20190405.12.

Footnotes

[1] Maghradze, D., et al. (2016). Grape and wine culture in Georgia, the South Caucasus. 39th World Conference of Vine and Wine, BIO Web of Conferences 7 (03027); Lortkipanidze, D. (ed.). (2017). Georgia the cradle of viticulture. National Geographic Magazine - Georgia in collaboration with the Georgian National Museum. Available at: <https://nationalgeographic.ge/story/georgia-the-cradle-of-viticulture/>.

[2] Gelashvili, A. (2024). The Revived Legend of Mukhrani. Sandro Books Publishing; Lordkipanidze, D. (ed.). (2017). Georgia the cradle of viticulture. National Geographic Magazine - Georgia in collaboration with the Georgian National Museum. Available at: <https://nationalgeographic.ge/story/georgia-the-cradle-of-viticulture/>.

[3] National Statistics Office of Georgia. (2024). Exports by commodity groups (HS 2 digit level) in 2015-2024. Export. Available at: <https://www.geostat.ge/en/modules/categories/637/export>.

[4] Zivzivadze, L., Taktakishvili, T. (2019). Index-based analysis of Georgian wine export’s competitiveness on a global market. International Journal of Agricultural Economics, 4(5), pp. 201-206. Available at: <https://sciencepublishinggroup.com/article/10.11648/j.ijae.20190405.12>.

[5] Anderson, K. (2020). Is Georgia the next ‘new’ wine-exporting country? Chapter 13 in The international economics of wine. World Scientific Studies in International Economics, 73, pp. 311-346; Anderson, K. (2012). Rural development in Georgia: what role for wine export growth? Wine Economics Research Centre Working Paper, 0112; Anderson, K. (2009). Wine’s New World. Foreign Policy. Available at: <https://foreignpolicy.com/2009/11/02/wines-new-world/>.

[6] Beyond the niche: the past, present & future of Georgian wine in the US market. (2021). Wines of Georgia. Available at: <https://winesgeorgia.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/Georgia-301-Virtual-Seminar-26-Aug-2021.pdf>; Georgian wine eyes USA market. (2021, September 23). Georgian Journal. Available at: <http://georgianamerica.com/eng/news/georgian_wine_eyes_usa_market_2744>.

[7] Granik, L. (2019, July 29). Understanding the Georgian wine boom. Seven Fifty Daily. Available at: <https://daily.sevenfifty.com/understanding-the-georgian-wine-boom/>.

[8] Rytkönen, P., Vigerland L., Borg, E. (2021). Tales of Georgian wine: storytelling in the Georgian wine industry. Journal of Wine Research, 32(2), pp. 117-133.

[9] Marketing research of wine tourism sector in Georgia. (2014, December 20). International Business Development and Investment Promotion Center.

[10] Tsereteli, M. (2018, December 7). Georgian wine and its narrative drive development. The Central Asia – Caucasus Analyst. Available at: <https://www.cacianalyst.org/publications/analytical-articles/item/13548-georgian-wine-and-its-narrative-drive-development.html>; Tsereteli, M., Oliker, O., Mankoff, J. (2019, January). Wine, society, and geopolitics. Center for Strategic and International Studies. Available at: <https://csis-website-prod.s3.amazonaws.com/s3fs-public/event/190307_Tsereteli_WineSociety_pageproofs5.pdf>.

[11] Gelashvili, A. (2024). The Revived Legend of Mukhrani. Sandro Books Publishing.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Dinello, N. (2022). Centrality of winemaking in Georgia: from prehistoric age to present-day globalization. Journal of Wine Research, 33(3), pp. 123-145.

[14] Tsinandali Estate Museum. (2024). Available at: <http://tsinandali.ge/en/museum/about-us>.

[15] Gelashvili, A. (2024). The Revived Legend of Mukhrani. Sandro Books Publishing; World’s Best Vineyards. (2024). 47 Château Mukhrani, Mukhrani, Georgia.

[16] Anderson, K. (2012). Rural development in Georgia: what role for wine export growth? Wine Economics Research Centre Working Paper, 0112.

[17] USAID/Georgia’s Economic Security Program: Mid-Term Evaluation (2022, June). Final Report, pp. 33, 41, 43-44. Available at: <https://pdf.usaid.gov/pdf_docs/PA00ZGXC.pdf>.

[18] USAID Economic Security Program. (2023, January 15). Quarterly report. Quarter 1 FY23: October – December 2022. Available at: <https://pdf.usaid.gov/pdf_docs/PA02122H.pdf>.

[19] USAID Agriculture Program. (2023). Unlocking potential for Georgian wine in US markets. Cultivating New Frontiers in Agriculture (CNFA).

[20] Georgia - regional development project. (2012, February 22). World Bank Group.

[21] Agenda.ge. (2024, April 26). Georgia, FAO sign new $4m project to boost sustainable agriculture, rural development. Available at: <https://agenda.ge/en/news/2024/38857#gsc.tab=0>.

[22] LEPL National Wine Agency. (2024). Available at: <https://wine.gov.ge/En/Page/mainactivities>.

[23] Transparency International, Georgia. (2023, February 23). Georgia’s economic dependence on Russia: impact of the Russia-Ukraine war.

[24] IMF Country Report No. 24/135. (2024, May). Georgia: 2024 article IV consultation—press release, staff report, and statement by the executive director for Georgia.

[25] Transparency International, Georgia. (2023, February 23). Georgia’s economic dependence on Russia: impact of the Russia-Ukraine war.

[26] Transparency International, Georgia. (2024, February 16). Georgia’s economic dependence on Russia: summary of 2023.

[27] Von Cramon-Taubadel, S., Saha, D. (2015, May). Short-run risks and long-run challenges for wine production in Georgia. Policy Paper Series, German Economic Team Georgia and ISET Policy Institute, Berlin/Tbilisi, 7.

[28] National Statistics Office of Georgia. (2024). External trade portal. Available at: <https://ex-trade.geostat.ge/en>.

[29] Transparency International, Georgia. (2024, February 16). Georgia’s economic dependence on Russia: summary of 2023.

[30] National Statistics Office of Georgia. (2024). External trade portal. Available at: <https://ex-trade.geostat.ge/en>; Transparency International, Georgia. (2024, February 16). Georgia’s economic dependence on Russia: summary of 2023.

[31] Buckley, N. (2013, February 4). Georgian wine to flow as Russia lifts ban. Financial Times. Available at: <https://www.ft.com/content/13269432-6ee9-11e2-9ded-00144feab49a>; Sharkov, D. (2016, March 3). Russian imports of Georgian wine skyrocket after ban is lifted. Newsweek. Available at: <https://www.newsweek.com/russian-imports-georgian-wine-skyrocket-after-lifted-ban-434698>.

[32] The Embassy of Georgia to the United States of America. (2021). High-level trade dialogue (HLTD). Available at: <https://georgiaembassyusa.org/bilateral-trade/>.

[33] Mercer, C. (2023, May 24). Which countries drink the most wine? Ask Decanter. Decanter. Available at: <https://www.decanter.com/wine-news/which-countries-drink-the-most-wine-ask-decanter-456922/>.

[34] Colangelo & Partners (2024). Available at: <https://www.colangelopr.com/>.

[35] Teliani Valley. (2024). Available at: <https://www.telianivalley.com/en>.

[36] Interview with Kvelaidze, T. (2024, June 3).

[37] National Statistics Office of Georgia. (2024). External trade portal Available at: <https://ex-trade.geostat.ge/en>.

[38] Gambashidze, D. (2023, July 31). Georgian wine is gearing up to strengthen its position in the US market. Forbes.

[39] Anderson, K., Pinilla, V. (2021). Wine’s belated globalization, 1845–2025. AAEA Agricultural & Applied Economics Association – Wiley, pp. 750, 761-762.

[40] Numbeo. (2024). Price rankings by country of bottle of wine (mid-range) (markets). Available at: <https://www.numbeo.com/cost-of-living/country_price_rankings?itemId=14>.

[41] National Wine Agency of Georgia. Export of wine and alcoholic beverages. (2024, February 9).

[42] Interview with Mgvdliashvili, Z. (2024, June 7).

[43] Gambashidze, D. (2023, July 31). Georgian wine is gearing up to strengthen its position in the US market. Forbes.

[44] Interview with Peterson, J. (2024, June 5).

[45] Enterprise Georgia. (2024). Free trade regimes.

[46] National Statistics Office of Georgia. (2024). External trade portal. Available at: <https://ex-trade.geostat.ge/en>.

[47] Interview with Kvelaidze, T. (2024, June 3).

[48] Mercer, C. (2023, May 24). Which countries drink the most wine? Ask Decanter. Decanter. Available at: <https://www.decanter.com/wine-news/which-countries-drink-the-most-wine-ask-decanter-456922/>.

[49] World Population Review. (2024). Wine producing countries 2024. Available at: <https://worldpopulationreview.com/country-rankings/wine-producing-countries>.

[50] Mercer, C. (2023, May 24). Which countries drink the most wine? Ask Decanter. Decanter. Available at: https://www.decanter.com/wine-news/which-countries-drink-the-most-wine-ask-decanter-456922/>; World Population Review. (2024). Wine producing countries 2024. Available at: <https://worldpopulationreview.com/country-rankings/wine-producing-countries>.

[51] Georgian National Tourism Administration. (2023). Georgian tourism in figures: structure and industry data 2022. Available at: <https://gnta.ge/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/2022-eng-1.pdf>.

[52] Georgian National Tourism Administration. (2024). Conducted Activities. International Visitors Survey. Available at: <https://gnta.ge/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/International-Visitor-Survey-2023.xlsx>.

[53] Georgian National Tourism Administration. (2023). Georgian tourism in figures: structure and industry data 2022. Available at: <https://gnta.ge/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/2022-eng-1.pdf>.

[54] Extension - University of Georgia. (2024). Georgia’s Alcoholic Beverage Industry 2024 Outlook.

[55] Quinn, C. (2020, April 1). The tourism industry is in trouble. Foreign Policy. Available at: <https://foreignpolicy.com/2020/04/01/coronavirus-tourism-industry-worst-hit-countries-infographic/>.

[56] Shamugia, E. (2023, October 17). Tourism: Georgia and the region. Forbes: Georgia. Available at: <https://forbes.ge/en/tourism-georgia-and-the-region/>.

[57] Georgia National Tourism Administration. (2024, February 12). Record $4.1 billion in tourism revenue and 7.1 million international travelers - 2023 statistics.

[58] National Statistics Office of Georgia. (2024). Inbound tourism statistics in Georgia. Available at: <https://www.geostat.ge/media/59934/Inbound-Tourism-Statistics---%282023-year%29.pdf>.

[59] Ibid.

[60] Georgia National Tourism Administration. (2024). International visitor survey 2015-2023. Available at: <https://gnta.ge/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/International-Visitor-Survey-2023.xlsx>.

[61] Georgian National Tourism Administration. (2023). Georgian tourism in figures: structure and industry data 2022. Available at: <https://gnta.ge/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/2022-eng-1.pdf>; National Statistics Office of Georgia. (2024). Inbound tourism statistics in Georgia. <https://www.geostat.ge/media/59934/Inbound-Tourism-Statistics---%282023-year%29.pdf>.

[62] Interviews with Honnef, P. (2024, May 24), Peterson, J. (2024, June 5), & Sauvage, O. (2024, May 5).

[63] National Statistics Office of Georgia. (2024). Exports by commodity groups (HS 2 digit level) in 2015-2024. Export. Available at: <https://www.geostat.ge/en/modules/categories/637/export>.

[64] Tsereteli, M. (2018, December 7). Georgian wine and its narrative drive development. The Central Asia – Caucasus Analyst. <https://www.cacianalyst.org/publications/analytical-articles/item/13548-georgian-wine-and-its-narrative-drive-development.html>.

[65] Jmukhadze, N. (2022. August 1). The role and influence of wine export on the economic growth of Georgia. Forbes. Available at: <https://forbes.ge/en/ghvinis-eqsportis-roli-da-gavlena-saqarthvelos-ekonomikur-zrdaze/>.

Downloads

Downloads

Published

Issue

Section

License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.