Hofstede’s National Cultural Dimensions in the Managerial Context (Case study)

DOI:

https://doi.org/10.35945/gb.2024.18.012Keywords:

Hofstede’s cultural dimensions, individualism vs collectivism, short-long term orientation, managementAbstract

Efficient management is crucial for organizational development, considering the diverse national cultures worldwide. Solid empirical and theoretical knowledge exists globally to study cultural dimensions’ role in this context. However, findings cannot be generalized to every culture, including Georgia, without local research on values and characteristics. This study aimed to identify Georgian society’s cultural dimensions, influenced by both Western and Eastern elements due to its unique geographical position and context. Understanding these dimensions is essential for effective human resource management and cross-cultural cooperation in organizations, facilitating successful business activities.

The literature review highlights how national culture impacts management practices, citing studies by various scholars. The research employed Hofstede’s cultural dimensions framework, updated with insights from five major Georgian cities, using quantitative methods to ensure representative findings.

Comparing the dimensional scores of cultural orientations of Polish culture studied similarities and differences, driven by shared history and regional proximity. The study’s innovative approach addresses gaps in empirical cross-cultural management research in Georgia, offering recommendations for leadership and HR management in local organizations. Hypotheses were formulated and tested using self-administered surveys and SPSS software, confirming Georgia’s individualistic tendencies and moderate long-term orientation. Differences between educational levels and national comparisons with Poland were also explored, revealing insights into cultural orientations. Limitations consider studying only two dimensions and five cities in the country.

Keywords: Hofstede’s cultural dimensions, individualism vs collectivism, short-long term orientation, management.

Introduction

This research aimed to explore Georgia’s unique cultural dimensions, shaped by both Western and Eastern influences, to inform effective human resource management and cross-cultural cooperation.

The literature review discusses how national culture impacts management, referencing studies by different authors. Using Hofstede’s[1] cultural dimensions framework, the study conducted a quantitative analysis in five major Georgian cities. It compared Georgian cultural traits with Polish culture, identifying both similarities and differences due to shared history and regional context. The study offers new insights into Georgia’s cultural orientations, with findings on individualism and long-term orientation, and explores the impact of education levels. However, it is limited by its focus on just two cultural dimensions and five cities.

Literature Review

Hofstede’s Cross-Cultural Model

Welzel and colleagues[2] identified three key factors driving cultural change: socioeconomic shifts, value changes, and political institutions. Socioeconomic changes include technological innovation, improved health and life expectancy, higher income, better education, and increased access to information. The second factor is market expansion, while the third involves political institutions, particularly efforts to enhance democracy. To understand Georgian culture, it’s important to consider these influences from the country’s recent past. Hofstede and Bond[3] introduced the concept of “Long-term versus short-term orientation” based on the Chinese Value Survey (CVS). The study compared students from 23 countries to highlight these cultural differences.

The Implications of National Culture in Management

Tarhini and colleagues[4] highlight the reciprocal influence between culture and organizational processes, where culture impacts business practices and vice versa. A diverse environment is seen as a valuable opportunity in business.[5] It was suggested that HR practices are shaped by managers’ perceptions of workers and tasks,[6],[7] which are, in turn, influenced by their cultural orientation.[8] Additionally, it was emphasized that the concepts of self and personality, linked to individualistic cultures, play a key role in branding and advertising.[9] In collectivist societies, self-identity is shaped by the social context, with behavior varying according to the situation.[10] Marketers use various strategies to build loyalty among current and potential customers, with branding often incorporating personality, especially in individualistic cultures. Hofstede and colleagues noted that long-term-oriented traders focus on building lasting relationships and partnerships based on trust, while those with short-term orientation prefer more immediate, transactional interactions. People from individualistic cultures aim to fulfill their potential. Plim and his colleagues found that individualism, long-term focus, and indulgence are key cultural factors that support national innovation.[11]

Polish Cultural Orientation

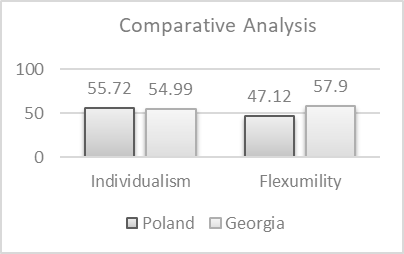

Poland’s shared Communist past likely influenced its long-term versus short-term orientation. However, according to Hofstede’s Insights, Polish society now has a moderately individualistic orientation (55) and an intermediate score (47) for Flexibility vs. Monumentalism (FLX/MON). Poland’s geographical location, surrounded by Western individualistic countries, also plays a role in shaping its cultural orientation.

Factors Influencing on Georgian Culture

Georgian historian Giorgi Anchabadze presents the significant influence of Soviet rule on Georgia’s cultural and economic development. During the period from 1801 to 1878, Georgia was under Russian imperial control, freedom of speech was suppressed, and harsh punishments on dissenters were imposed. Despite attempts at independence, Georgia fell under Soviet rule, where private property was abolished, industries nationalized, and dissenters persecuted. The Soviet era brought industrialization, collectivization of agriculture, and cultural suppression, stifling artistic expression and limiting economic opportunities. The collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991 resulted in economic downturns across former member states, including Georgia, marking a significant shift in its socio-economic landscape. In conclusion, the literature suggests that in this context, competition in the market was not prioritized, quantity outweighed quality, and there were limited development opportunities across all fields. Hence, the system upheld collectivistic values in Georgian society.[12]

Ganesan views investment as a key indicator of long-term orientation,[13] while investing in education is considered as crucial for productivity and well-being. Although quality education doesn’t guarantee employment or full potential, it increases the chances of success. There is a high demand for higher education, as many students apply for National Unified Exams each year. Additionally, in Georgia’s banking sector, various types of savings deposits are offered to help customers save for the future, with different durations and modest returns, illustrating another example of long-term orientation.[14]

As Georgia transitioned from socialism to capitalism, individuals gained the right to own businesses and private property, reflecting a shift toward Western values. The country joined international organizations, including the Council of Europe,[15] World Trade Organization.[16] Former President Eduard Shevardnadze expressed interest in joining NATO[17] and the European Union.[18] The Georgian population strives to get close to European Union and Western values.

Notably, a geographical factor of the country can potentially influence neighboring countries. Specifically, Russia scored 56 in FLX/MON and 57 in Individualism/Collectivism. The score is intermediate but above 50. If we go through the previous (2017-2021) and current (2022-2030) Strategic plans of the Ministry of Education and Science of Georgia, Internationalization is a key strategy in higher and professional education, emphasizing the importance of becoming more globally oriented rather than ethnocentric.

Methodoloy

Minkov and Hofstede used data from the World Values Survey to redefine Long-Term Orientation. Their subsequent work, particularly the study by Minkov introduced an updated dimension named Monumentalism-Flexumity. The following model classifies nations into Monumentalist cultures, prevalent in regions like the Middle East and Africa, which emphasize mutual assistance and reputation, and Flexumility cultures, which prioritize flexibility and adaptability.[19] The study considered applying a quantitative approach to generalize findings across a population, ensuring precision through statistical analysis of substantial raw data obtained from respondents. This analysis aimed to identify the indices of several cultural dimensions.[20]

Validation of the Model

The model, widely used by authors at Hofstede’s Insights Center, has been utilized to conduct in more than 54 national cultures, using a revised framework by Michael Minkov[21]. Calculating scores for dimensions was performed through regression analysis. In our study, regression analysis was applied alongside published indices from other countries provided by Hofstede’s Insights Center.[22]

Research Instrument

In the framework of the study, we utilized an instrument about cultural values provided by the Hofstede Research Center. The survey was meticulously formed by specialized groups, including psychologists. It comprised 102 items on a three-level scale, covering topics related to culture, personality, consumer behavior, and demographic information. The use of forced-choice items enabled precise measurement of concept intensity compared to free-choice items. The instrument was translated into the local language and back to verify accuracy, and each item was contextualized to ensure semantic equivalence. The research sample consisted of individuals with at least a high school education, evenly split between genders.

Research Design of Study N1

The sample for the following study was randomly selected from five major cities to ensure equal opportunity for potential respondents to participate. This approach, grounded in both empirical and theoretical frameworks, aimed for a representative sampling method. The questionnaire was distributed in two stages to reach the desired number of responses, considering past low response rates with lengthy questionnaires. Initially sent to 630 individuals, 122 incomplete responses were excluded, resulting in a 75% response rate from 472 participants who completed all questions. Cross-checking questions helped filter out illogical responses, yielding data from 468 respondents, balanced.

Research Design of Study N2

Focused on understanding Georgians’ past experiences, this study calculates scores for IND/COL and LO/ST Orientation. Applying to Hofstede’s Insights Research Center’s precise sampling methodology, data was analyzed from respondents with higher education levels. This approach allows for comparison of aggregated means and scores from previous studies with a larger sample of 200 respondents, comprising 111 females and 89 males, distributed across Tbilisi (59), Kutaisi (46), Batumi (29), Rustavi (39), and Zugdidi (27).

This research also incorporates comparing Georgian cultural indices of Ind/Coll and FlX/MON with those of Polish society. The selection of Poland is justified by its geographical proximity to Georgia and shared historical influence, characterized by collectivistic values and short-term orientation similar to Georgia. The following survey was employed to gather data from both nations, facilitating direct comparison.

Research Findings

Findings of Study N1

According to the obtained data from all age groups, the calibrated equation yielded a score of approximately 59.45 for the Individualism/Collectivism (IND/COLL) dimension in Georgian society, whereas the regression analysis indicated a score of approximately 54.05. This suggests that Georgian culture leans towards individualism. Conversely, on the Flexumility/Monumentalism (FLX/MON) dimension, Georgia scored lower with a calibrated score of approximately 17.66 and a regression-based score of 57.4, indicating a long-term-oriented culture. In summary, the study confirms the first and second hypotheses that Georgian culture is both individualistic and long-term oriented. Despite potential deviations attributed to the research instrument, the general orientation remains consistent, albeit potentially slightly lower in score.

Findings of Study N2

In both samples, Georgian society demonstrated consistent tendencies towards individualism and long-term orientation. Despite the small differences, the IND scores were 54.05 and 54.9, and the LTO scores were 57.4 and 57.9. In conclusion, it is anticipated that Georgian society needs certain time and generational change to increase scores in the following dimensions. A shift towards Western values is expected among younger people with modern education and less Soviet influence.

Research Findings of Study N3

Despite differences among nations, comparing cultural orientations based on two dimensions through scores provides interesting insights. Using aggregated mean data from Hofstede’s Insights Research Center, we rescaled and converted cultural scores to a 0-100 scale, applying regression analysis to evaluate each orientation’s level. It’s notable that, for cross-cultural comparisons, we utilized scores from a smaller sample (the individuals with only high school education) similar to other countries. In terms of scores, Poland got around 55.72 on the scale for IND/COLL and around 47.12 for FLX/MOM. The scores underline Polish culture’s higher level of individualism compared to Georgian society, while Polish scores for Flexumility-Monumentalism were lower than those for Georgia. Polish society exhibited higher individualism scores than Georgian society. However, Georgian culture showed higher scores for Long-Term Orientation (LTO).

Figure 1 – Comparative scores.

Source: Author’s research

The differences in the Flexumility dimension may stem from factors such as social desirability bias, varying sample sizes, and data being collected at different times.

Research limitatins

Every study has limitations. Scholars agree that larger sample sizes lead to more accurate representations of the general population, so expanding the sample size in each city could be a focus for future research. Additionally, including more cities would provide a more accurate evaluation of cultural dimensions at the national level. The current model does not analyze other dimensions based on survey data, so we cannot confirm the existence of dimensions like power distance or indulgence vs. restraint. We hope future research will develop a more comprehensive model with relevant items for analysis. It was emphasized that nations may not be the best unit of analysis for cultural differences, as countries often contain various subcultures. They also noted that culture is dynamic and evolving due to globalization, technology, and other challenges. Therefore, it’s important to periodically study cultural dimensions to maintain up-to-date knowledge for future development.[23]

Conclusion

The study underscores the critical importance of examining national cultural orientations across various domains. The theoretical framework highlighted in the research underscores how cultural dimensions significantly impact organizational behavior and related fields.

In addressing the empirical gap within the Georgian cultural context, this research employed a meticulous methodology encompassing diverse target groups and precise sample selection. By calculating dimensional scores from two distinct samples, the study revealed insights into the lingering influence of the Soviet experience on older generations.

The findings, derived from both smaller and comparative analyses with over 50 other national cultures studied by Hofstede’s Insights Research Center, yielded compelling results, particularly in the comparison of Georgian and Polish cultures. The hypotheses concerning Individualism orientation were substantiated, with intermediate scores. Similarly, the acceptance of Georgian society’s Long-Term Orientation aligns with the study’s expectations despite some non-significant variables in regression analysis. Surprisingly, Polish culture exhibited a lower score in Long-Term Orientation compared to Georgian culture while demonstrating a higher Individualism orientation.

Despite its limitations, this study holds implications for organizational contexts in Georgia. The theoretical foundation offers robust insights into cultural dimensions’ role in organizational development. Generalizable findings at the national level can inform management practices, ensuring organizational alignment with cultural preferences. Recommendations for managing individualistic orientations include promoting fairness, involving employees in decision-making, implementing formal job appraisal systems, offering motivating rewards, granting autonomy, and providing developmental opportunities. Team-building efforts should be prioritized for tasks requiring collective effort among individuals with the following orientation. Lastly, management should engage in ongoing dialogue regarding long-term organizational goals and invest in employee professional development to support long-term employment. Flexibility in managing human resources across Georgian and Polish societies is crucial.

In conclusion, this study and its insights into cultural orientations offer valuable guidance for scholars and managers navigating organizational development challenges.

Bibliography:

- Anchabadze, G. (2005). History of Georgia: A short sketch. Caucasian House;

- Aycan, Z., Kanungo, R. N., Sinha, J. P. (1999). Organizational Culture and Human Resource Management Practices: The Model of Culture Fit. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology. <https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022199030004002>;

- Buller, P. F., McEvoy, G. M. (2012). Strategy, Human Resource Management and Performance: Sharpening Line of Sight. Human Resource Management Review, 22(1);

- Ganesan, S. (1994). Determinants of Long-Term Orientation in Buyer-Seller Relationships. Journal of Marketing, 58(2). Retrieved from <https://doi.org/10.1177/002224299405800201>;

- Hofstede, G., Bond, M. (1988). The Confucius connection: From cultural roots to economic growth. Organizational Dinamics, Elsevier, 16(4);

- Hofstede, G. (2011). Dimensionalizing cultures: the Hofstede model in context Online Readings Psychology and Culture., 2 (1) (2011). International Association for Cross-Cultural Psychology, 2(1);

- Hofstede’s Insights. (n.d.). Retrieved March 30, 2022, from <https://hi.hofstede-insights.com/about-geert-hofstede>;

- Lenartowicz, T., Roth, K. (2001). Does subculture within a country matter? A cross-cultural study of motivational domains and business performance in Brazil. Journal of International Business Studies, 32(2). doi:10.1057/palgrave.ji;

- Ludviga, I. (2009). Measuring Cultural Diversity: Methodological Approach and Practical Implications; Assessment in Latvian. The International Journal of Diversity in Organisations, Communities and Nations, 9(3);

- Markus, H. (1991). Culture and the self: implications for cognition, emotion and motivation. Research Gate, 98(6);

- Minkov, M., Hofstede, G. (2012) Hofstede’s Fifth Dimension: New Evidence from the World Values Survey. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 43. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0022022110388567

- Minkov, M. (2018). A revision of Hofstede’s model of national culture: Old evidence and new data from 56 countries. Cross-Cultural and Strategic Management, 25(2);

- Minkov, M. (2018b). What values and traits do parents teach their children? New data from 54 countries. Comparative Sociology, 17(2);

- Mooij, M. D. (2015, January). The Hofstede Model Application to Global Branding and Advertising Strategy and Research. International Journal of Advertising, 29(1);

- Prim, A. L., Filho, L. S., Luiz, C., Zamur, G. A. (2017, June). The Relationship Between National Culture Dimensions and Degree of Innovation. International Journal of Innovation Management, 21(3).

- Tarhini, A., Hone, K., Liu, X., Tarhini, T. (2016). Examining the Moderating Effect of Individual-level Cultural values on Users’ Acceptance of E-learning in Developing Countries: A Structural Equation Modeling of an extended Technology Acceptance Model. Interactive Learning Environments. <https://doi.org/10.1080/10494820.2016.1183183>;

- Weisbrod, B. A. (1996). Education and Investment in Human Capital. Journal of Political Economy, 70(5). Retrieved from <https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/abs/10.1086/258728>;

- Welzel, C., Inglehart, R., & Klingemann, H.-D. (2003). The theory of human development and the development of human theory. Political Psychology, 24(3). <https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6765.00086>;

- Council of Europe. Georgia. Council of Europe, accessed June 26, 2022. <https://www.coe.int/en/web/portal/georgia>.

- World Trade Organization. Georgia and the WTO: Accessions. World Trade Organization, accessed December 21, 2021. <https://www.wto.org/english/thewto_e/acc_e/a1_georgia_e.htm>.

- InfoCenter of the Government of Georgia. NATO and Georgia: History. InfoCenter, accessed December 21, 2021. <https://infocenter.gov.ge/en/nato-georgia/nato-georgia-history/>.

- Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Georgia. Georgia–European Union Relations: Key Events Chronology. Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Georgia, accessed December 25, 2021. <https://mfa.gov.ge/en/european-union/903144-saqartvelo-evrokavshiris-urtiertobebis-mnishvnelovani-movlenebis-qronologia>.

Footnotes

[1] Hofstede, G. (2011). Dimensionalizing cultures: The Hofstede model in context. Online Readings in Psychology and Culture, 2(1). International Association for Cross-Cultural Psychology

[2] Welzel, C., Inglehart, R. Klingemann, H. D. (2003). The Theory of Human Development and the Development of Human Theory, Political Psychology 24(3), pp. 493–511. <https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6765.00086>.

[3] Hofstede, G., Bond, M. (1988). The Confucius Connection: From Cultural Roots to Economic Growth. Organizational Dynamics 16(4), pp. 5–21.

[4] Tarhini, A., Hone, K., Liu, X., Tarhini, T. (2016). Examining the Moderating Effect of Individual-Level Cultural Values on Users’ Acceptance of E-Learning in Developing Countries: A Structural Equation Modeling of an Extended Technology Acceptance Model. Interactive Learning Environments. <https://doi.org/10.1080/10494820.2016.1183183>.

[5] Ludviga, I. (2009). Measuring Cultural Diversity: Methodological Approach and Practical Implications; Assessment in Latvian. The International Journal of Diversity in Organisations, Communities and Nations 9(3), pp. 67–78.

[6] Aycan, Z., Kanungo, R. N., Sinha, J. P. (1999). Organizational Culture and Human Resource Management Practices: The Model of Culture Fit. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology. <https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022199030004002>.

[7] Buller, P. F., McEvoy, G. M. (2012). Strategy, Human Resource Management and Performance: Sharpening Line of Sight. Human Resource Management Review 22(1), pp. 43–56.

[8] Hofstede, G., Bond, M. (1988). The Confucius Connection: From Cultural Roots to Economic Growth. Organizational Dynamics 16(4), pp. 5–21.

[9] Mooij, M. D. (2015). The Hofstede Model Application to Global Branding and Advertising Strategy and Research. International Journal of Advertising 29(1), pp. 84–110.

[10] Markus, H. (1991). Culture and the Self: Implications for Cognition, Emotion, and Motivation. Research Gate 98(6), pp. 224–246.

[11] Prim, A. L., Filho, L. S., Luiz, C., Zamur, G. A. (2017). The Relationship Between National Culture Dimensions and Degree of Innovation. International Journal of Innovation Management, 21(3), pp. 5-8.

[12] Anchabadze, G. (2005). History of Georgia: A short sketch. Caucasian House.

[13] Ganesan, S. (1994). Determinants of Long-Term Orientation in Buyer-Seller Relationships. Journal of Marketing 58(2), pp. 1–19. <https://doi.org/10.1177/002224299405800201>.

[14] Weisbrod, B. A. (1996). Education and Investment in Human Capital. Journal of Political Economy 70, no. 5. <https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/abs/10.1086/258728>.

[15] Council of Europe. Georgia. Council of Europe, accessed June 26, 2022 <https://www.coe.int/en/web/portal/georgia>.

[16] World Trade Organization. Georgia and the WTO: Accessions. World Trade Organization, accessed December 21, 2021. <https://www.wto.org/english/thewto_e/acc_e/a1_georgia_e.htm>.

[17] InfoCenter of the Government of Georgia. NATO and Georgia: History. InfoCenter, accessed December 21, 2021. <https://infocenter.gov.ge/en/nato-georgia/nato-georgia-history/>.

[18] Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Georgia. Georgia–European Union Relations: Key Events Chronology. Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Georgia, accessed December 25, 2021. <https://mfa.gov.ge/en/european-union/903144-saqartvelo-evrokavshiris-urtiertobebis-mnishvnelovani-movlenebis-qronologia>.

[19] Minkov, M., Hofstede, G. (2012). Hofstede’s fifth dimension: New evidence from the World Values Survey. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 43, pp. 2–14. <https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022110388567>.

[20] Minkov, M. (2018). A revision of Hofstede’s Model of National Culture: Old Evidence and New Data from 56 Countries. Cross-Cultural and Strategic Management 25(2), pp. 231–256.

[21] Minkov, M. (2018b). What values and traits do parents teach their children? New data from 54 countries. Comparative Sociology, 17(2)

[22] Hofstede’s Insights. (n.d.). About Geert Hofstede. Retrieved March 30, 2022, from https://hi.hofstede-insights.com/about-geert-hofstede

[23] Lenartowicz, T., Roth, K. (2001). Does Subculture Within a Country Matter? A Cross-Cultural Study of Motivational Domains and Business Performance in Brazil. Journal of International Business Studies 32(2), pp. 269–279. <https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.ji>.

Downloads

Downloads

Published

Issue

Section

License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.