The Banking Regulation’s Shifts in Light of Globalization and its Effect on the Banking Industry’s Performance: U.S.A. as a Model

DOI:

https://doi.org/10.35945/gb.2024.18.005Keywords:

Banking Regulation, Performance, Globalization, United States, Dodd-Frank ActAbstract

Banking regulation is essential for the efficient functioning of banking activities and the optimal allocation of financial resources. It also plays a critical role in ensuring financial stability and safeguarding depositors by preventing banks from taking excessive risks and ensuring they maintain adequate liquidity to meet their obligations. These measures contribute to the development of the banking sector and enable banks to finance economic growth. This study seeks to examine the transformations in banking regulation over recent decades and their impact on the performance of the banking sector, focusing on the United States as a case study. To achieve this objective, a descriptive method was employed. The study found that banking regulation in the United States has undergone significant transformations, shifting from liberalization to increased restrictions. The global financial crisis of 2008 prompted regulators to tighten their frameworks, which, while initially having a slight negative impact on profitability, ultimately had a significant positive effect on the resilience of banks.

Keywords: Banking Regulation, Performance, Globalization, United States, Dodd-Frank Act.

- Introduction

The global economy had a significant increase in liberalization throughout the last years of the previous century; the surge in banking sector activity and cross-border capital flows is predominantly attributed to the advent of financialization. However, this was paralleled by an increase in the levels of risks faced by the banking system in countries around the world, leading to a series of successive crises.

If a bank fails, it can have far-reaching economic consequences, particularly if the bank is considered to be systemically significant. Depositors, including individuals and corporations, face the risk of losing their deposited funds, which might potentially lead to a complete cessation of economic activity. This situation necessitates placing the banking sector within a framework that includes a set of rules and regulations to ensure its proper functioning and foster a high level of trust between the banking sector and other sectors. However, these laws and standards frequently make it difficult for the banking industry to grow and restrict high-yield, high-risk banking operations, which has an impact on the industry’s overall performance.

The American banking sector is considered one of the most dynamic internationally. For decades, this sector has experienced extensive regulatory activity that alternates between liberalization and restriction, occurring simultaneously with disruptions to the American economy. Banking regulation is now an essential tool for properly supervising this important sector in a manner that protects the interests of the American economy without endangering taxpayer dollars.

Considering the worldwide financial crisis and its substantial impact on the banking sector and the broader economy, there was a clear and important change in banking regulation in the United States, primarily involving an increase in regulatory constraints. This shift led to a divided American society: some supported regulation as necessary for the safety of the banking sector, while others opposed it, arguing that it burdens banks and significantly affects their performance. Therefore, this study aims to present the regulatory reform experience in the United States, the world’s leading economy, and highlight its effects on the performance of the American banking sector, with a focus on the period following the 2008 subprime mortgage crisis.

- Fundamentals of Banking Regulation

2.1. Concept of Banking Regulation

Financial regulation refers to the set of rules and regulations that control the operations of businesses in the financial industry. Examples of entities include asset managers, banks, credit unions, insurance companies, and financial intermediaries. The Central Bank of Ireland has issued this proclamation, which mandates compliance with certain regulations. However, financial regulation requires ongoing monitoring and enforcement of these rules in addition to the mere implementation of regulations.[1]

Spong defines banking regulation as specifically the body of laws and rules that control how banks conduct business. Banking supervision and banking agencies are distinct from each other. While banking supervision focuses on the enforcement of banking rules and regulations and the monitoring of financial conditions in banks, banking agencies operate under their direction.[2]

Banking regulation, as defined by (Agborya-Echi, 2010),[3] refers to the collection of governmental rules established to supervise and control financial institutions. Banking regulation may be described as: “a collection of laws and regulations that oversee banking activities with the goal of fostering discipline and transparency in banking operations”.

2.2. Types of Banking Regulation

There are two broad categories of regulations that affect banks: regulations for the soundness and safety of banks and regulations for consumer protection:[4]

2.2.1. Safety and Soundness Regulation

This kind of oversight makes sure that banks run soundly and safely, not putting taxpayers or deposit insurance money at undue risk. Usually, the activities of the bank and the regulatory systems that oversee and examine these activities are the main subjects of these rules.

2.2.2. Consumer Protection Regulation

Protecting consumers’ interests when they interact with banks and other financial service providers is the aim of these regulations. This set of legislation covers a wide variety of issues, including prohibiting discrimination in credit transactions, protecting consumers from misleading information, and ensuring that they are properly informed about how credit expenses related to loans and leases are calculated.

2.3. Motivations for and Objectives of Banking Regulation

Banking institutions are regulated for two main reasons:[5]

2.3.1. Consumer Protection

This reason is similar to why public utilities and telecommunications are regulated, which is to provide a framework of rules that can help prevent market mechanisms alone from controlling market excesses and failures.

2.3.2. Achieving Financial Stability

Preserving financial stability is often seen as a crucial public advantage that necessitates the creation of a more extensive system for overseeing and controlling.

The primary goals of banking regulation are as follows:[6]

- Ensuring the security and soundness of banks and other financial institutions is crucial to protect depositors and taxpayers, maintain financial stability, and uphold trust at both the national and global levels. Furthermore, it ensures the optimal utilization of the state’s finite resources and the central bank’s dedication to serving as the ultimate provider of funds for banks during periods of necessity;

- Achieve Monetary Stability and Maintain Efficient Payment System Operations: This includes ensuring that the monetary system is stable and that the payment systems operate efficiently;

- Create an Efficient and Competitive Financial System: This is achieved by preventing the excessive concentration of banking resources, which would otherwise lead to non-competitive conditions;

- Protect Consumers and Customers: This involves safeguarding borrowers against the arbitrary practices of credit-granting institutions by ensuring that consumers have equal opportunities to obtain the required credit.

- Banking Regulation in The Context of Globalization

3.1. Drivers of Banking Regulatory Transformation

There are two components to the historical process of financial globalization. First, there is a rise in the amount of cross-border financial transactions; second, a series of institutional and regulatory reforms have been put in place to liberalize local financial systems and global capital movements.[7]

Throughout the second half of the 20th century, there were numerous changes to banking regulations that affected the global economy. These changes were brought about by a number of interrelated factors, such as the development of various forms of regulatory evasions, such as offshore financial centers and off-balance-sheet financing methods, the rapid advancement of technology, and the declining efficacy of traditional controls as a result of financial innovation. International financial center rivalry, nonbank competition for a range of services (including mortgages, small business loans, and consumer credit), and multilateral accords also played a role in the liberalization of cross-border banking activity.[8]

3.2. Evolution of International Banking Regulation Between Liberalization and Restriction:

The degree of restriction in banking safety standards has changed throughout time. Safety and soundness rules were very strict after the Great Depression, with a focus on keeping commercial and investment banking services separate and forbidding bank-holding corporations from partnering with insurance companies.

Significant limitations on market forces, such as controls over interest rates, caps on the volume of business financial institutions could undertake, barriers to market access, and, in certain situations, restrictions on financing allocation, were features of financial systems in the early 1970s. Governments used these regulatory restrictions to further their social and economic policy objectives. In several post-war nations, direct controls were employed to direct funding toward businesses of choice. Financial stability concerns contributed to limitations on market access and competition, and safeguarding small savers with little financial literacy was a key goal of bank supervision.

Since the mid-1970s, there has been a significant regulatory reform effort in place in the financial systems of most countries. In this process, there was a shift towards more market-oriented regulatory structures, as the table below illustrates:

Table (01): Partial or Full Liberalization Measures in the Financial Sector since the Mid-1970s

|

Field |

Partial or complete liberalization |

|

Controls on interest rates |

Most nations had extensive lending and borrowing restrictions in place up until the early 1970s. Banks controlled credit for preferred borrowers, and both rates were kept below levels of the free market. Only a few nations still had these restrictions in place by 1990. |

|

Restrictions on the transfer of funds internationally and the exchange of currencies |

In many developing countries as well as in OECD countries, the liberalization of capital movement regulations is almost complete. Nonetheless, there are still certain restrictions on long-term capital movements, mainly with regard to foreign direct investment and foreign ownership of real estate. |

|

Distinction between investment banking and commercial banking operations |

While many nations still impose considerable limitations on commercial lines, in many instances these limitations have been significantly reduced or eliminated entirely. |

|

Quantitative limits on banking institutions’ investments |

Banks were subject to a variety of investment limitations, such as mandates to hold government securities and guidelines for credit allocation. The early 1990s saw the complete elimination of these restrictions. |

Source: Biggar & Heimler, 2005.

The above regulatory restraints were gradually lifted, although this did not result in the total emancipation of banking operations. Rather, it led to the implementation of new prudential regulatory instruments that better fit the banking industry’s competitive landscape. The first and most notable step in this new regulatory approach is the Basel Agreements. Large multinational banks in a group of twelve countries were required by the Basel I Accord, which was signed in July 1988, to begin achieving an 8% minimum capital adequacy ratio in 1992. Basel III: The subprime mortgage crisis prompted the committee to release its most recent version of its recommendations. After that, the committee made improvements to these plans in response to global economic shocks.

- Effects of Regulation on the Banking Sector’s Performance

4.1. Mechanism for Implementing Banking Regulation

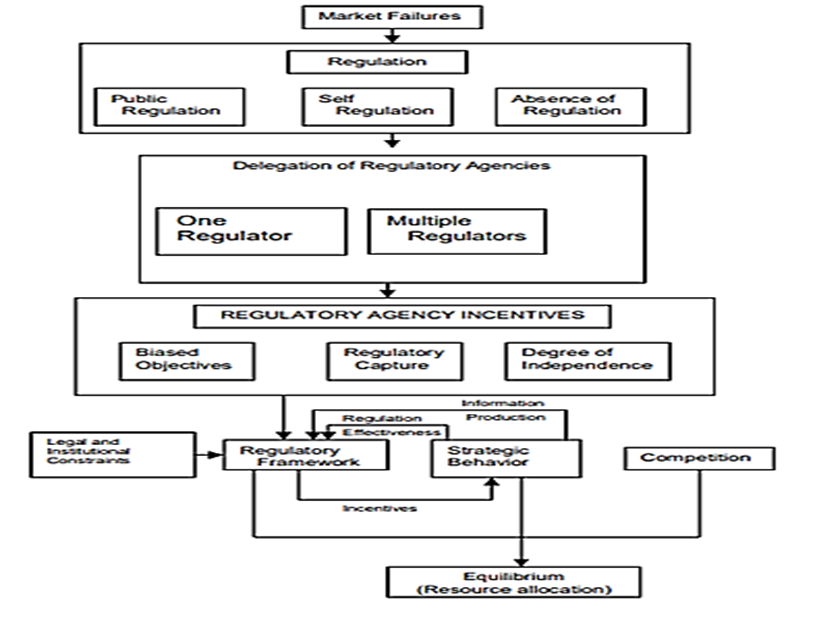

People might make the error of believing that powerful regulatory organizations only act in the public interest and that regulated institutions would abide by laws if they concentrated on the best regulatory method to remedy a specific market failure. In actuality, banking regulation is an economic game in which each player formulates a plan of action based on their personal goals. It is unrealistic to expect regulators to accomplish their objectives in a society where legislative structures limit their authority. It is also important to keep in mind that banks will adapt to regulations by creating new plans, such as offering financial innovations.[9]

The mechanism by which banks interact with banking regulation can be summarized in the following figure:

Figure (01): Mechanism for Implementing Banking Regulation

Source: Freixas & Santomero, 2002.

4.2. Theories on How Banking Regulation Affects Bank Performance

There are two contradictory arguments in the theory of banking regulation and its importance, outlined as follows:[10]

4.2.1. Public Interest Theory

According to this hypothesis, the regulation of banking enhances the overall performance of banks by preventing new competitors from entering the market and thereby decreasing competition. Because there is less competition, banks are compelled to provide more cautious loans, which lowers banking risks. If there is no rivalry in the banking business, banks would only lend to borrowers with excellent credit ratings, but if there is fierce competition, banks may lend to customers with lower credit ratings. Moreover, this theory argues that direct bank supervision and control by government supervisors and regulators might eliminate financial failures entirely. Supporters of this viewpoint include Psillaki and Mamatzakis (2017)[11] and Beck et al. (2006).[12]

4.2.2. Private Interest Theory

This financial regulation theory contends that contrary to the public interest view, stringent regulation has a negative impact on bank performance since it raises fee responsibilities. Entry restrictions make it harder for banks to innovate and operate efficiently, which makes them more dependent on more expensive funding sources like equity. As a result, riskier portfolios are chosen to offset high expenses and risk-taking brought on by high capital requirements, which lowers bank performance. According to this theory, stringent banking regulations result in unethical capital allocation, unscrupulous lending practices, and, eventually, poor bank performance, which may lead to bank closures. Supporters of this view include Laeven and Levine (2008)[13] and Pasiouras et al. (2009).[14]

4.3. The Impact of Banking Regulation on Bank Performance

Different conclusions may be drawn from an examination of the research on how regulation affects bank performance. While some studies have demonstrated a beneficial relationship between regulation and bank performance, others have found a somewhat negative relationship.[15] assert that big banks gain from more freedom to raise the risks in their asset portfolios and that they engage in riskier behaviors more frequently when there is less supervision over them.[16] discovered that financial laws, which limit financial activity, may aid banks in achieving financial stability and help avert systemic issues.

On the other hand, (Jomini, 2011)[17] argues that strict and harsh regulations can lead to high costs and poor performance due to the additional expenses incurred by regulated banks to comply with and manage these regulations. Since extensive regulations reduce competition, they also reduce economies of scale and innovation. Similarly, (Klomp & Haan, 2015)[18] concluded that stricter banking regulation improves bank performance. They explained that restrictive regulations reduce banking risks in large foreign banks, while liquidity constraints affect smaller banks. Additionally, they contended that banking regulation greatly impacts high-risk institutions while having less effect on low-risk banks.

- Uniqueness and Evolution of U.S Banking Sector Regulation

5.1. Uniqueness of U.S. Banking Sector Regulation

The stability of the United States is of paramount importance to the global economy. The banking system is considered one of the most important financial systems globally because of its intricate nature, interconnectivity, and breadth.

Compared to other nations, bank regulation in the US is extremely dispersed. In contrast to most other nations, which only have one bank regulatory agency, the United States has state and federal bank regulations. A financial institution may be governed by several federal and state banking laws, depending on its size and organizational design.

In addition, the US has federal and state regulating bodies for commodities, insurance, securities and exchange, and banking in addition to the banking industry. This is in contrast to nations like the United Kingdom and Japan, where different domains are unified under a single regulatory agency.

The table below illustrates the regulatory authorities that oversee the banking industry in the United States:

Table (02): Regulatory Bodies of the U.S. Banking Sector

|

Regulatory power |

The provided function |

|

|

|

The Federal Reserve Board (FRB) |

The federal Reserve, in its role as the country’s central bank, supervises monetary policy with the aim of sustaining low long-term interest rates, ensuring price stability, and attaining optimal employment levels in the American economy. Furthermore, its primary goal is to improve financial stability and efficiently manage and supervise risks that might impact the entire system.[19] |

|

|

|

The FDIC is the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation |

This independent agency was established by Congress to supervise and examine financial institutions to ensure their safety and soundness, provide deposit insurance, and reassure the public that complex, large-scale financial institutions can be resolved. The major objectives of this institution are to preserve the stability of the nation’s financial system and sustain public trust.[20] |

||

|

The entity referred to as the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC) |

Created by the United States Department of the Treasury, the organization is responsible for establishing and enforcing regulations, and overseeing all national banks and federal savings institutions—including foreign bank branches and agencies—is the responsibility of this independent authority. The organization ensures impartial treatment of clients, equal opportunity to obtain financial services, secure and stable bank operations under its oversight, and adherence to all applicable rules and regulations.[21] |

||

|

The Bureau of Consumer Financial Protection (CFPB) |

The objective is to enhance consumer financial markets for the advantage of conscientious providers, consumers, and the overall economy. It protects customers against unjust, exploitative, or deceptive commercial activities and initiates legal proceedings against those who violate the law. Moreover, it provides individuals with the information, tools, and activities necessary to make prudent financial choices.[22] |

||

|

The Council for Financial Stability Oversight (FSOC) |

The council is tasked with evaluating the susceptibilities that may impact the stability of the US financial system, strengthening market discipline, and reacting to new dangers to that stability. By imposing risk-based capital requirements and limitations on short-term loans, including procedures for off-balance sheet transactions, it keeps an eye on big financial institutions. The council sets yearly stress tests, restricts leverage between 15% and 1%, and mandates that these businesses submit plans for an orderly resolution in the case of financial difficulties.[23] |

||

Source: Prepared by researchers relying on the official websites of the regulatory authorities and offices.

5.2. Evolution of U.S. Banking Sector Regulation

The 1929 stock market crisis caused economic instability and ultimately resulted in the banking system collapsing, which made stricter banking regulations necessary. The Glass-Steagall Act of 1933 was responsible for creating the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) and requiring the separation of commercial and investment banking operations. The New Deal implemented regulations on deposit interest rates. The 1935 Banking Act enhanced and consolidated the power of the Federal Reserve.

There was some relative banking stability and economic growth between the New Deal banking reforms and 1980. However, it soon became evident that stringent banking laws limited American banks’ ability to innovate and remain competitive. Stricter regulation-bound commercial banks were falling behind more innovative, loosely regulated financial businesses. Consequently, there was an increase in the process of removing regulations over the latter two decades of the 20th century.

The Depository Institutions Deregulation and Monetary Control Act was passed by Congress in 1980; the Federal Reserve was given additional authority to determine monetary policy, and financial institutions that received deposits were liberalized. The Riegle-Neal Interstate Banking and Branching Efficiency Act of 1994 eliminated the prohibitions on bank branch openings that were imposed on a state-by-state basis.

The 1999 Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act eliminated the restrictions set by the Glass-Steagall Act, therefore permitting banks to conduct commercial banking activities, securities, and insurance services all under one organization. Both the number of banking institutions and the volume of financial transactions increased throughout the next few years.[24]

- Contemporary Banking Regulation In The U.S

6.1. U.S. Banking Sector’s Response to Basel III Accords

U.S. regulatory authorities have implemented the Basel III accords within the local banking regulations, highlighted by the following:

6.1.1. Capital Adequacy Ratio

The key rules imposed include:[25]

- A bank must maintain a minimum of 4.5% of its capital in Common Equity Tier 1 (CET1). In addition, banks must have a 2.5% buffer for capital conservation on common shares. These laws require banks to maintain a total of 7% CET1 capital by the end of 2019. As a result, banks will need to retain 10.5% capital by the end of 2019 in addition to the 2.5% countercyclical buffer;

- The overall capital requirement for banks using the advanced strategy can be as high as 13%. This comprises the countercyclical buffer and the capital conservation buffer, which started at 0% and has the potential to increase to 2.5% by the end of 2019;

- The start date for compliance with the minimum capital requirement was January 1, 2014, for financial organizations utilizing the sophisticated methodology (generally, people or corporations must have a minimum of $250 billion in total assets or at least $10 billion in on-balance sheet international exposure). The start of 2015 was the compliance start date for other banking institutions;

- In order to circumvent limitations on dividend payouts and discretionary bonuses, advanced approach banks must maintain a combined buffer (capital conservation and countercyclical) of more than 5%. Banks are obliged to maintain a countercyclical buffer.

6.1.2. Liquidity Ratios

September 2014 saw the announcement of the final Liquidity Coverage Ratio (LCR) regulation by U.S. banking authorities, with a few minor deviations. The standards are closely akin to those of Basel III. The proposed liquidity coverage ratio (LCR) applies to both US banking institutions and major non-bank financial firms. Bank-holding organizations with assets over $250 billion must maintain an adequate amount of liquid assets to meet net cash withdrawals within 30 days. For a regional organization with assets ranging from $50 billion to $250 billion, it is necessary for its liquid assets to be enough to cover net cash withdrawals within a 21-day timeframe. Bank holding firms are exempt from the LCR if their assets do not exceed $50 billion.[26]

The United States has adopted the Net Stable Funding Ratio (NSFR) in line with global standards, and enforcement began in January 2018.

6.1.3. Leverage ratio

One of the largest benefits of the Basel III requirements is the leverage ratio. The Basel Committee revised the methods for determining exposures both on and off the balance sheet in January 2014, and in 2010, it established a leverage ratio of 3%.

The 3% leverage ratio was put into effect by US regulatory bodies in 2013 as part of an examination of capital requirements. Large financial institutions with total consolidated assets of at least $250 billion or foreign exposure on their balance sheet of at least $10 billion are subject to this ratio.

U.S. authorities finalized the new leverage ratio, which was set at 6% for insured depository institutions and globally systemically important banks (G-SIBs). Banking authorities finalized these regulations in April 2014.[27]

6.2. The Dodd-Frank Act: Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection

The Dodd-Frank Act As a reaction to the global economic recession, the Obama administration implemented the Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act of 2010 as part of a broader legislative effort to overhaul the financial industry. This law’s objectives are to safeguard American taxpayers by ending bailouts, enhancing financial system accountability and transparency, dismantling the “too big to fail” theory for major corporations, and protecting customers from deceptive financial services activities.

The following are the main rules and clauses included in the Dodd-Frank Act:[28]

- Greater Quantity and Quality of Capital: The Dodd-Frank Act mandates that banks maintain greater amounts of capital of higher caliber by conforming to the international Basel III standards, which establish minimum risk-weighted capital levels, liquidity requirements, and leverage requirements. Systemically important financial institutions are subject to more stringent requirements;

- Annual Stress Tests: In order to promote market trust and transparency, institutions are put through annual stress tests;

- Government agencies changed the Act to provide more efficient supervision of the financial system as a whole. The Thrift Supervision Office was closed, and the Federal Reserve and the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC) currently share the responsibilities with the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC). The Federal Reserve acted as the main regulatory body for major financial enterprises. Additionally, the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) of the Federal Reserve and the Financial Stability Oversight Council (FSOC) under the Treasury were formed by Congress;

- Bailouts are specifically terminated by the Dodd-Frank Act, which is paid by taxpayers. According to Section 214, the financial industry is responsible for any losses incurred in the liquidation of any financial institution; taxpayers will not be held liable for such losses;

- Large banks are required to file comprehensive resolution plans;

- The Financial Stability Oversight Council (FSOC) was created with the aim of detecting risks that might potentially affect the whole financial system. It has jurisdiction over both non-bank financial firms and banks;

- Financial institutions that benefit from government deposit guarantees are prohibited from participating in proprietary trading for personal profit or to invest in hedge funds and private equity funds, but they are permitted to contribute up to 3% of their capital to these funds.[29]

- Performance of the U.S Banking Sector in the Light of Contemporary Banking Regulation

7.1. Capital Adequacy Ratio in the U.S. Banking Sector

By bringing its banking system into compliance with Basel III requirements, the American banking industry has responded to the many directives and guidelines issued by regulatory bodies. The improvement of the capital adequacy ratio, which offers a capital buffer to absorb losses from unforeseen operational, credit, or market events, has been one of the main results.

Table (03): Evolution of Tier 1 Capital Ratio from 2006 to 2019

|

Year |

2006 |

2007 |

2008 |

2009 |

2010 |

2011 |

2012 |

2013 |

2014 |

|

|

|

Tier 1 Core Capital |

8.33 |

7.13 |

6.31 |

8.67 |

10.2 |

10.9 |

11.6 |

12.8 |

13.1 |

|

|

|

Year |

2015 |

2016 |

2017 |

2018 |

2019 |

2020 |

2021 |

2022 |

2023 |

||

|

Tier 1 Core Capital |

13.1 |

13.2 |

13.5 |

13.8 |

13.7 |

14.5 |

14.8 |

14.5 |

14.9 |

||

Source: International Monetary Fund (IMF), 2020.

The Tier 1 capital ratio, which represents the best quality capital, has significantly improved, as the table demonstrates. The Tier 1 capital ratio decreased to around 6% at the onset of the global financial crisis, down from over 8% in 2006. However, it subsequently increased to 13.1% in 2014. The percentage remained consistently high in the subsequent years, concluding at 13.8% in 2023. This development shows how effective regulations have been in strengthening the stability of American financial institutions.

Within this particular framework, there was a significant decrease in the quantity of banking institutions with insufficient capitalization subsequent to the worldwide financial crisis, as depicted in the subsequent table:

Table (04): Evolution of the Percentage of Undercapitalized Banking Institutions in

The United States (2006-2019) (End of Period)

|

Year |

2006 |

2007 |

2008 |

2009 |

2010 |

2011 |

2012 |

|

Less Capitalized Institutions/Total Institutions |

1.04 |

1.58 |

4.36 |

6.24 |

5.57 |

4.66 |

3.59 |

|

Year |

2013 |

2014 |

2015 |

2016 |

2017 |

2018 |

2019 |

|

Less Capitalized Institutions/Total Institutions |

2.67 |

1.8 |

1.43 |

1.05 |

0.83 |

0.52 |

0.42 |

Source: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve, 2019.

A notable decrease in the number of financial institutions with inadequate capital is indicated by Table 05. These decreases coincided with the introduction of new regulations meant to raise capital adequacy ratios. By the end of 2011, the percentage of these undercapitalized institutions had dropped from 6.24% at the height of the financial crisis to 4.66%. By the end of 2016, the percentage had dropped below 1.05% in accordance with the Basel implementation plan that was suggested. The percentage of these institutions has decreased to about 0.42% by the middle of the year.

The decline in the proportion of undercapitalized banking institutions is indicative of the effectiveness of banking reforms in this domain and shows how resilient the American banking industry has become in comparison to the years before the financial crisis.

7.2. Evolution of Profitability Rates in the U.S. Banking Sector

Profitability rates, namely the return on assets and return on equity, serve as indications of banking institutions’ capacity to create financial returns. The capital adequacy ratio’s development in the US banking industry is displayed in the following table.

Table (05): Both Return on Equity and Return on Assets in the U.S. Banking Sector (2006-2019) (End of Period)

|

Year |

2006 |

2007 |

2008 |

2009 |

2010 |

2011 |

2012 |

2013 |

2014 |

|

|

|

ROA |

1.28 |

0.81 |

0.04 |

-0.07 |

0.65 |

0.88 |

1 |

1.07 |

1.01 |

|

|

|

ROE |

12.31 |

7.75 |

0.36 |

-0.72 |

5.87 |

7.8 |

8.91 |

9.54 |

9.01 |

||

|

Year |

2015 |

2016 |

2017 |

2018 |

2019 |

2020 |

2021 |

2022 |

2023 |

||

|

ROA |

1.04 |

1.04 |

0.97 |

1.35 |

1.29 |

0.72 |

1.23 |

1.11 |

1.1 |

||

|

ROE |

9.29 |

9.29 |

8.61 |

11.98 |

11.38 |

6.85 |

12.21 |

11.82 |

11.5 |

Source: Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC), 2024.

The table illustrates a significant decrease in both return on equity (ROE) and return on assets (ROA) during the 2008 global financial crisis. In 2006, the return on assets (ROA) was 1.28%; by 2008, it had dropped to 0.04%, while the return on equity (ROE) had risen from 12.31% to -0.72% in 2009. Even if the US economy is recovering, by the end of 2010, the ROA remained below its pre-crisis level, reaching 0.65% at the end of 2010. It began to rise again in 2012 but remained nearly stable at around 1%. The ROE, although it rebounded after the crisis, never returned to its end-of-2006 level. This decline in profitability is attributed to the stringent capital and liquidity requirements that limited banking activity levels during this period.

7.3. The Volume of Non-Performing Loans in the U.S. Banking Industry

The incidence of non-performing loans in the American banking industry increased before the start of the global financial crisis and reached its peak during the crisis. The table below illustrates the progression of the non-performing loan to total loan ratio in the US banking industry from 2006 to 2019.

Table (06): Trends in the Non-Performing Loan Ratio in the U.S. Banking Sector (2006-2019)

|

Year |

2006 |

2007 |

2008 |

2009 |

2010 |

2011 |

2012 |

2013 |

2014 |

|

|

|

Non-performing loans percentage |

0.8 |

1.4 |

3 |

5 |

4.4 |

3.8 |

3.3 |

2.5 |

1.9 |

|

|

|

Year |

2015 |

2016 |

2017 |

2018 |

2019 |

2020 |

2021 |

2022 |

2023 |

||

|

Non-performing loans percentage |

1.5 |

1.3 |

1.1 |

0.9 |

0.9 |

1.1 |

0.9 |

0.7 |

0.8 |

||

Source: International Monetary Fund (IMF), 2024.

The table indicates a substantial reduction in the non-performing loan ratio. The implementation of strict lending criteria and precise evaluation of borrowers’ creditworthiness led to a reduction in non-performing loans. The non-performing loan ratio decreased from 5% in 2009 to 1.9% at the end of 2014. The ratio dropped to 0.8% by the end of 2023, a low point akin to the two years preceding the financial crisis.

7.4. Liquidity of the U.S. Banking Sector

The implementation of the final Basel Accords resulted in a significant rise in the amount of highly liquid assets within the banking sector of the United States. The following table displays the evolution of high-liquidity assets, such as cash assets, government securities, and Treasury bonds, as a proportion of all assets held by US commercial banks.

Table (07): High-Liquidity Assets as a Percentage of Total Assets in the U.S. Banking Sector (2006-2019) (End of Period)

|

Year |

2006 |

2007 |

2008 |

2009 |

2010 |

2011 |

2012 |

2013 |

2014 |

|

|

|

High-quality liquid assets / Total assets % |

26 |

12.9 |

17.3 |

22.3 |

22.7 |

26 |

27.2 |

32 |

38.8 |

|

|

|

Year |

2015 |

2016 |

2017 |

2018 |

2019 |

2020 |

2021 |

2022 |

2023 |

||

|

High-quality liquid assets / Total assets % |

30.5 |

34.5 |

29.8 |

27.1 |

26.5 |

34 |

38.3 |

33 |

32.7 |

Source: Board of Governors of The Federal Reserve, 2023.

The suggested liquidity coverage ratio by monetary authorities considers the quantity of high liquidity assets held by American banks, and the table illustrates this rapid development. Between the end of 2014 and 2021, the proportion of liquid assets, including cash, agency securities, and Treasury bonds, rose from around 17.28% of the total assets during the global financial crisis to more than 38%. Although there was a small decrease in the proportion of easily convertible assets, it remains higher than the pre-2008 financial crisis levels. This trend highlights the American banks’ move towards implementing the liquidity coverage ratio and maintaining larger liquid asset reserves to withstand periods of stress. The increasing levels of liquid assets indicate a greater capacity for banks to handle potential stress scenarios.

Conclusion

Due to the global economic crises, there is significant interest in the need to decrease financial deregulation and reorganize the banking sector on a worldwide scale. This aims to regulate various transactions between the banking sector and related parties, ensuring financial consumer protection on the one hand and achieving financial stability on the other. Although there are varying perspectives among theorists and researchers on the influence of banking regulation on banking performance levels, some believe that banking regulation is essential for regulating competition, enhancing banking services, and reducing risk, while others see it as having a negative impact on banking performance.

In this context, the U.S. experience with banking regulation demonstrated the need for stringent application of the legislation during the 2008 global financial crisis, with an emphasis on safeguarding financial customers and enhancing the resilience and safety of systemically significant banking institutions. This had an impact on the banking industry’s cost structures, which temporarily reduced bank profitability. However, the banking industry’s resilience increased dramatically, as seen by a notable rise in the capital adequacy ratio and liquidity levels.

Bibliography:

- Agborya-Echi, A.-N. (2010). Financial regulations, risk management and value creation in financial institutions: Evidence from Europe and the U.S.A. (Master’s thesis). University of Sussex, UK;

- Almaw, S. (2018). The effect of bank regulation on the bank’s performance (Paper submitted for the partial fulfillment of the course Financial Institutions and Capital Market). College of Business and Economics, Bahir Dar University, Ethiopia;

- Barth, J. M., Caprio, G., Levine, R. (2004). Bank regulation and supervision: What works best? Journal of Financial Intermediation, 13(2). <https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfi.2003.06.002>;

- Beck, T. H. K., Demirguc-Kunt, A., Levine, R. (2006). Bank concentration, competition, and crises. Journal of Banking and Finance, 30(5);

- Biggar, D., Heimler, A. (2005). An increasing role for competition in the regulation of banks. International Competition Network Working Papers. Germany;

- Board of Governors of The Federal Reserve System. (2020). About the Fed. Federal Reserve. <https://www.federalreserve.gov/aboutthefed.htm> [Last Access 23.04.2024];

- Board of Governors of The Federal Reserve. (2023). Assets and liabilities of commercial banks in the United States: Weekly statistical releases, H.8. Federal Reserve. <https://www.federalreserve.gov/releases/h8/current/> [Last Access 28.06.2024];

- Central Bank of Ireland. (2010). What is financial regulation and why does it matter? Central Bank: <https://www.centralbank.ie/consumer-hub/explainers/what-is-financial-regulation-and-why-does-it-matter> [Last Access 20.04.2024];

- Consumer Financial Protection Bureau. (2020). About the Bureau. Consumer Financial Protection Bureau. <https://www.consumerfinance.gov/about-us/the-bureau/> [Last Access 23.04.2024];

- Corporation, Federal Deposit Insurance. (2020). About FDIC. FDIC. <https://www.fdic.gov/about> [Last Access 23.04.2024];

- Dempsey, M. C. (2017). Basel III regulation and the move toward uncommitted lines of credit. Lexology. <https://www.lexology.com/library/detail.aspx> [Last Access 01.05.2024];

- Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC). (2024, June 11). FDIC quarterly. FDIC. <https://www.fdic.gov/analysis/quarterly-banking-profile/fdic-quarterly/index.html> [Last Access 28.06.2024].

- Fell, J., Schinasi, G. (2005). Assessing financial stability: Exploring the boundaries of analysis. National Economic Review, 192(1). <https://doi.org/10.1177/002795010519200110>;

- Financial Stability Oversight Council (FSOC). (2020). About FSOC. U.S. Department of the Treasury. <https://home.treasury.gov/policy-issues/financial-markets-financial-institutions-and-fiscal-service/fsoc/about-fsoc> [Last Access 23.04.2024];

- Freixas, X., Santomero, A. (2002). An overall perspective on banking regulation. Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia Working Papers, No. 01-1. U.S.A.;

- Frenkel, R. (2003). Globalization and financial crises in Latin America. CEPAL Review, 80;

- Getter, D. (2014). US implementation of Basel capital regulatory framework. Congressional Research Service, U.S.A.;

- International Monetary Fund (IMF). (2020). Financial soundness indicators. IMF. <https://data.imf.org/regular.aspx?key=63174545> [Last Access 28.06.2024];

- International Monetary Fund (IMF). (2024, July 23). Financial soundness indicators (FSIs). IMF Data. <https://data.imf.org/?sk=51b096fa-2cd2-40c2-8d09-0699cc1764da&sid=1411569045760> [Last Access 28.06.2024];

- Johnston, M. (2019, June 25). A brief history of U.S. banking regulation. Investopedia. <https://www.investopedia.com/articles/investing/011916/brief-history-us-banking-regulation.asp> [Last Access 01.05.2024];

- Jomini, P. A. (2011, March). Effects of inappropriate financial regulation (Policy Brief). Sciences Po, France;

- Klomp, J., Haan, J. d. (2015). Bank regulation and financial fragility in developing countries: Does bank structure matter? Review of Development Finance, 5(2). <https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rdf.2015.11.001>;

- Laeven, L., Levine, R. (2008). Bank governance, regulation, and risk-taking. NBER Working Papers, 14113. Cambridge;

- Markovich, S. J. (2013, December 10). The Dodd-Frank Act. Council on Foreign Relations. <https://www.cfr.org/backgrounder/dodd-frank-act> [Last Access 02.05.2024];

- Mashaie, M. (2013). Profitability and lending: An analysis of systemically important banks pre-2007–09 financial crisis (Unpublished master’s thesis). University of Ottawa, Department of Economics;

- Mohanta, A. (2014). Impact of Basel III liquidity requirements on the payments industry: Liquidity management strategy for banks providing payment services. CAPGEMINI Consulting Technology Outsourcing;

- Office of the Comptroller of the Currency. (2020). About the OCC. Office of the Comptroller of the Currency. <https://www.occ.treas.gov/about/who-we-are/index-who-we-are.html> [Last Access 23.04.2024];

- Pasiouras, F., Tanna, S., Zapounidis, C. (2009). Banking regulations, cost and profit efficiency: Cross-country evidence. International Review of Financial Analysis, 18(5). <https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbankfin.2005.05.010>;

- Psikalli, M., Mamatzakis, E. (2017). What drives bank performance in transition economies? The impact of reforms and regulations. Research in International Business and Finance, 39. <https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ribaf.2016.09.010>;

- Quintyn, M. G., Taylor, M. W. (2004). Should financial sector regulators be independent? Economic Issues, 32;

- Schmidt, J., Willardson, N. (2004, June 1). Banking regulation: The focus returns to the consumer. Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. <https://www.minneapolisfed.org/article/2004/banking-regulation-the-focus-returns-to-the-consumer> [Last Access 20.04.2024];

- Sims, P. (2013). The Dodd-Frank Act: Goals and progress. Hamilton Place Strategies;

- Spong, K. (2000). Banking regulation: Its purposes, implementation, and effects. Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City, U.S.A.

Footnotes

[1] Central Bank of Ireland. (2010). What is financial regulation and why does it matter? <https://www.centralbank.ie/consumer-hub/explainers/what-is-financial-regulation-and-why-does-it-matter> [Last Access 20.04.2024].

[2] Spong, K. (2000). Banking regulation: Its purposes, implementation and effects. Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City, U.S.A.

[3]Agborya-Echi, A. N. (2010). Financial regulations, risk management and value creation in financial institutions: Evidence from Europe and U.S.A. (Master’s thesis, University of Sussex, UK).

[4] Schmidt, J., Willardson, N. (2004, June 1). Banking regulation: The focus returns to the consumer. <https://www.minneapolisfed.org/article/2004/banking-regulation-the-focus-returns-to-the-consumer> [Last Access 20.04.2024].

[5] Quintyn, M. G., Taylor, M. W. (2004). Should financial sector regulators be independent? Economic Issues, 32, 2.

[6] Mashaie, M. (2013). Profitability, and lending: An analysis of systemically important banks pre-2007-09 financial crisis (Master’s thesis, University of Ottawa, Department of Economics).

[7] Frenkel, R. (2003). Globalization and financial crises in Latin America. CEPAL Review, 80, 39–51.

[8] Biggar, D., Heimler, A. (2005). An increasing role for competition in the regulation of banks. International Competition Network Working Papers, Germany, 3–4.

[9] Freixas, X., Santomero, A. (2002). An overall perspective on banking regulation. Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia Working Papers, No. 01-1, U.S.A., 11.

[10] Almaw, S. (2018). The effect of bank regulation on the bank’s performance. Paper submitted for the partial fulfillment of the course Financial Institutions and Capital Market. Ethiopia: College of Business and Economics, Bahir Dar University, 6.

[11] Psikalli, M., Mamatzakis, E. (2017). What drives bank performance in transition economies? The impact of reforms and regulations. Research in International Business and Finance, 39, 587–594. <https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ribaf.2016.09.010>.

[12] Beck, T. H. K., Demirguc-Kunt, A., Levine, R. (2006). Bank concentration, competition, and crises. Journal of Banking and Finance, 30(5), 1581–1603.

[13] Laeven, L., Levine, R. (2008). Bank governance, regulation, and risk taking. NBER Working Papers, 14113, Cambridge.

[14] Pasiouras, F., Tanna, S., Zapounidis, C. (2009). Banking regulations, cost, and profit efficiency: Cross-country evidence. International Review of Financial Analysis, 18(5), 294–302. <https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbankfin.2005.05.010>.

[15] Barth, J. M., Caprio, G., Levine, R. (2004). Bank regulation and supervision: What works best? Journal of Financial Intermediation, 13(2), 205–248. <https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfi.2003.06.002>.

[16] Fell, J., Schinasi, G. (2005). Assessing financial stability: Exploring the boundaries of analysis. National Economic Review, 192(1), 102–117. <https://doi.org/10.1177/002795010519200110>.

[17] Jomini, P. A. (2011, March). Effects of inappropriate financial regulation. Policy Brief, Sciences Po, France.

[18] Klomp, J., Haan, J. D. (2015). Bank regulation and financial fragility in developing countries: Does bank structure matter? Review of Development Finance, 5(2), 82–90. <https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rdf.2015.11.001>.

[19] Board of Governors of The Federal Reserve System. (2020). About the Fed. <https://www.federalreserve.gov/aboutthefed.htm> [Last Access 23.04.2024].

[20] Corporation, Federal Deposit Insurance. (2020). About FDIC. <https://www.fdic.gov/about/> [Last Access 23.04.2024].

[21] Office of the Comptroller of the Currency. (2020). About the OCC. <https://www.occ.treas.gov/about/who-we-are/index-who-we-are.html> [Last Access 23.04.2024].

[22] Consumer Financial Protection Bureau. (2020). About the Bureau. <https://www.consumerfinance.gov/about-us/the-bureau/> [Last Access 23.04.2024].

[23] Financial Stability Oversight Council (FSOC). (2020). About FSOC. U.S.

<https://home.treasury.gov/policy-issues/financial-markets-financial-institutions-and-fiscal-service/fsoc/about-fsoc> [Last Access 23.04.2024].

[24] Johnston, M. (2019, 06 25). A Brief History of U.S. Banking Regulation. <https://www.investopedia.com/articles/investing/011916/brief-history-us-banking-regulation.asp> [Last Access 01.05.2024].

[25] Dempsey, M. C. (2017). Basel III Regulation and the Move Toward Uncommitted Lines of Credit. <www.lexology.com/library/detail.aspx> [Last Access 01.05.2024].

[26] Mohanta, A. (2014). Impact of Basel III liquidity requirements on the payments industry: Liquidity management strategy for banks providing payment services. CAPGEMINI Consulting Technology Outsourcing, 6.

[27] Getter, D. (2014). U.S. implementation of Basel capital regulatory framework. Congressional Research Service, U.S.A.

[28] Sims, P. (2013). The Dodd-Frank Act: Goals and progress. Hamilton Place Strategies, 2-4. U.S.A.

[29] Markovich, S. J. (2013, 12 10). The Dodd-Frank Act. <https://www.cfr.org/backgrounder/dodd-frank-act> [Last Access 02.05.2024].

Downloads

Downloads

Published

Issue

Section

License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.